The sexiness of a commercial airplane deal, especially one from an influential blue chip customer, is often presented by its two most important headline figures: How many aircraft were purchased and for how many billions of dollars. The multiplied list price is as close to pure fiction writing as you’ll see in this business, but the fine print buried neatly at the bottom of a press release may better explain a buyer’s modus operandi.

Delta Air Lines has a reputation as a shrewd buyer of airliners. But its decision-making process isn’t hung solely on an airplane’s price tag, its performance and the roles and requirements the carrier wants it to fill flying passengers over two decades (or much, much longer). Its current fleet was born from a hodgepodge of aircraft out of the 2008 merger with Northwest Airlines. That complexity drove the expansion of a maintenance operation that could keep everything running.

For Delta, flying the airplane is just one part of the formula in overall long-term strategy. The company’s Chief Operating Officer, Gil West, gave a look inside the driving forces behind the airline’s thinking and how it buys airplanes for the Widget.

“The way we look at it is total value creation,” said West in an interview with The Air Current last month. It’s dry way to say the variables in Delta’s equation for buying aircraft touch disparate parts of its enterprise, sometimes in very nontraditional ways. “And there are a lot of forms of that. I think most traditional airlines just look at the price of the aircraft as the variable, and look, that’s really important, I’m not downplaying how important that is.

“There’s other ways to create value with those partners; the airframers, the engine manufacturers, the component manufacturers,” said West. “Ultimately that plays heavy into the selection of what aircraft we buy, which engines are on the aircraft, what components ultimately we were able to select…on all those aircraft.”

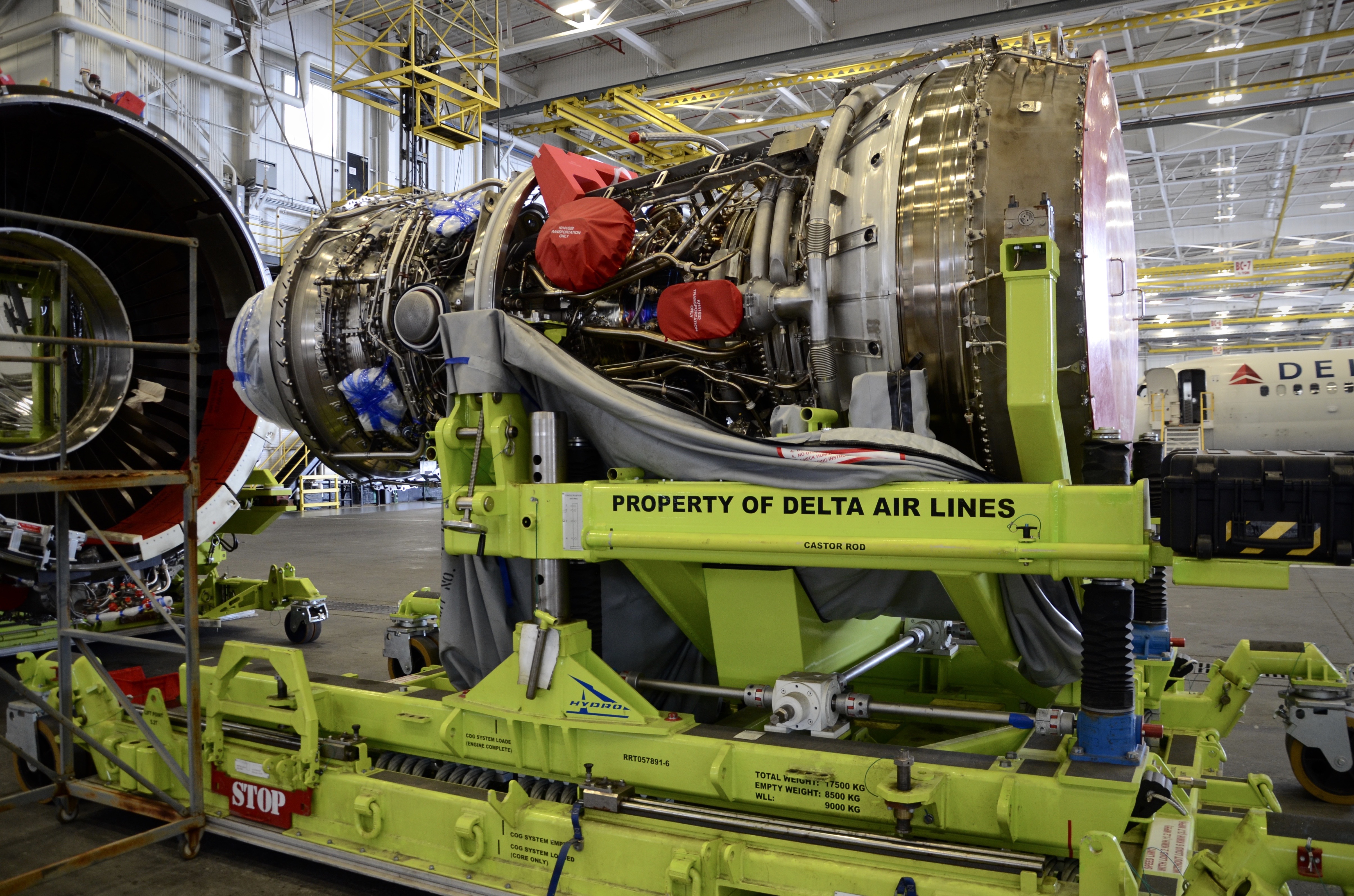

In its recent major large aircraft deals, the airline secured terms that extend well beyond the 175 combined Airbus A321neos and A220s (née CS100s). It cornered key parts of the aftermarket for engine overhauls for Pratt & Whitney’s PW1100G and PW1500G engines, which power both aircraft, respectively. Some 5,000 geared turbofan engine overhauls will be done at Delta TechOps as part of the agreement. Similar pacts accompanied its 2014 deals for Airbus A350 and A330neo aircraft, too, inking deals with Rolls-Royce to provide maintenance services for Trent XWB, 1000 and 7000 engines. As part of the infrastructure for these agreements, the airline recently inaugurated a $100 million engine test cell at its TechOps base in Atlanta. TechOps recently completed the first restoration of Trent 1000 for Virgin Atlantic’s 787 fleet, which has been waylaid by issues with their engines.

“The MRO piece of this created a lot of value for us in those deals, and relative to some of the other options we had, were pivotal in the decision, if not the overriding reason for the decision. So it is an extremely important aspect of what we ultimately decided,” said West, of the competitions against the competing Boeing products. Delta expects TechOps to contribute a $1 billion in revenue in 2019 and aims to double that before 2024, according to chief executive Ed Bastian.

Related: Rolls-Royce and the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad year

And it’s not just engines. The airline established Delta Flight Products (DFP) as part of a strategy to design interior components. “We paid a lot of people to do that and created a lot of companies out there in the marketplace who did that,” said West. “We said, well we could do this ourselves.

“They have the engineering capability to design, certify, manufacture, install all those ongoing interior modifications on our existing fleet. That was the genesis of Delta Flight Products originally. But then we quickly pivoted to, we can do this on new aircraft as well.”

West pointed to Delta’s seat back wireless in-flight entertainment systems, designed by DFP, that entered service on the A220 in February. Its first A330-900neos will feature the same system when its first aircraft arrives later this spring and on A321neos early next year, he said. “Those are the kinds of things that…as we evaluate aircraft, our ability to engineer and manufacture and provide product back to the OEMs is also an important variable in the equation.”

Related: Revisiting The Sporty Game 36 years later

Delta’s strategic approach blurs the line between the carrier as a traditional provider of air transport and its broader industry role. Its position is increasingly as an aviation conglomerate, and its operations place it at the nexus as both a customer and supplier to aircraft manufacturers and part of the maintenance ecosystem for airlines on their engines and aircraft.

“We look at it as, as a holistic equation,” said West, whose insight into the company’s broader business model also begins to offer a deeper explanation of its interest in Boeing’s notional 7K7 New Mid-Market Airplane (NMA).

West declined to comment on the airline’s interest in the NMA, instead deferring to Bastian’s early March comments about its interest in launching the aircraft. Delta has the potential to replace as many as 200 757s and 767s, retiring the aging workhorses that have been staples on both its U.S. transcontinental routes and transatlantic operations.

Both the decision to authorize sale of the airplane and a selection for the notional small twin-aisle aircraft are on the back burner as the company grapples with returning the 737 Max to service after it was grounded on March 13. NMA is “not a priority on [Boeing’s] agenda for now,” says a senior industry official familiar with Boeing’s thinking. The Air Current spoke with West two days prior to the March 10 crash of Ethiopian Airlines flight 302.

Related: Suppliers at arm’s length as Boeing heads for 797 decision

Yet the growing influence of the services business across the industry sets Boeing and Delta on a potential collision course for competition to win new aftermarket work. But the airline doesn’t just want to replace a segment of its fleet. It’s eager to buy into Boeing’s nascent network for providing services as part of its new Global Services division, according to those familiar with its strategy. That enables Delta to not just fly the NMA, but to provide services to airlines that purchase the airplane, too.

A Boeing spokesman declined to comment.

Regardless, the intersection of its TechOps business and fleet planning is going to be a part of any future aircraft purchases Delta makes, said West. “It’s a win-win and it plays very heavy into the overall economics, the total economics on the decisions we make for fleet. And that will continue into the future.”

Write to Jon Ostrower at jon@theaircurrent.com

Subscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention