Renton, Wash. — A Boeing airliner barred from flying passengers after two major safety events. An uncertain future for a critical program. An unsettled public. Regulators and politicians demanding answers. A reputation tarnished and a March press conference to pick up the pieces of the fractured trust and explain what comes next. It wasn’t 2019, it was 2013.

Almost six years ago to the week, Boeing executive Mike Sinnett was making the case to media in Tokyo about planned changes to the design of the 787 Dreamliner to reduce the risk of an incendiary runaway of the jet’s two powerful lithium ion batteries. Sinnett was then chief engineer of the program and its all-hands-on-deck development of a containment and venting system for the malfunctioning batteries would assuage regulators who had months earlier grounded the fleet.

Sinnett, again, is the face of Boeing’s engineering institution and now its Vice President of Product Strategy and Development. But for the second time in less than a decade, Boeing is having to defend its reputation and the safety of a core product. And Sinnett is acting as the sole voice on the software and training changes Boeing is making to the 737 Max following fatal crashes in Indonesia and Ethiopia that took the lives of 346 aboard and resulted in the global grounding of the single-aisle airliner earlier in March.

“We’re going to do everything we have to do to ensure accidents like these never happen again. We’re working with customers and regulators around the world to restore faith in our industry and also reaffirm our commitment to safety and earning the trust of the flying public,” Sinnett told media Wednesday morning near its commercial airplanes headquarters and not far from where it build’s the 737 Max.

Related: What is the Boeing 737 Max Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System?

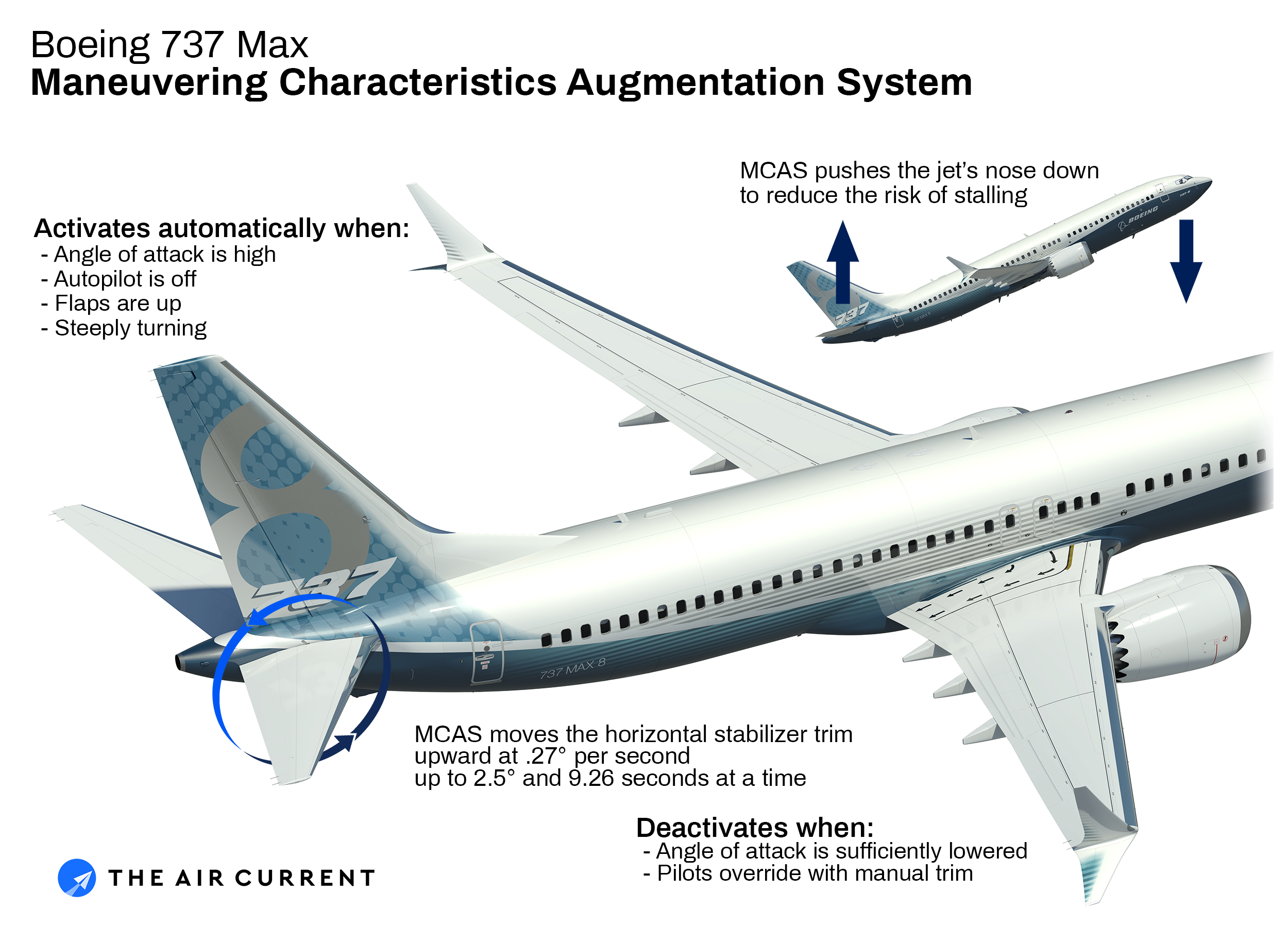

Sinnett detailed the changes coming to the 737 Max’s Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System function, which has been at the center of both investigations. The system is intended to assist pilots recovering from a stall at high speeds by pushing the jet’s nose down with the help of the tilting horizontal stabilizer. The changes, said Sinnett, “will eliminate the chance of erroneous data ever causing an MCAS activation.”

- The jet’s flight control system will collect data from two Angle of Attack sensors, instead of just one.

- The once-optional ‘AoA Disagree’ alert will be added to the primary flight display and the Angle of Attack (AoA) indication will be available at no cost if customers want it.

- In the event of a sensor failure (when the flaps are up) and the data from each sensor disagrees by more than 5.5 degrees, MCAS won’t activate. The AoA disagree indicator will alert pilots if this occurs.

- MCAS will only activate a single time for each indication of the jet’s angle of attack being too high.

- The movement of the horizontal stabilizer under MCAS will never exceed a pilot’s ability to override it by pulling back the yoke control “with sufficient maneuvering capability [so] that the airplane can still climb,” said Sinnett.

For pilots, the company has added additional training to make clear how MCAS functions and a new test at the end to ensure the material has been learned. In the wake of the Lion Air crash, Boeing warned airlines about the risk of erroneous AoA data activating MCAS and how to deactivate the system. Earlier, training or details on the MCAS system in many cases wasn’t included in the flight control operations manual at airlines like Southwest Airlines and American Airlines. Pilots transitioning from the 737 Next Generation to the 737 Max previously were limited to a single computer-based familiarization and required no testing.

The development of the software updates began immediately following the Lion Air crash on October 29. “We went through a process of developing software, deploying it, testing it, going back to our requirements, changing the software, deploying it, testing it. And so it took this amount of time to get it right,” said a Boeing official who did not want to be identified during a question and answer portion of the media briefing on the coming changes, citing concerns about attributed remarks during the on-going investigations. “We didn’t rush it because rushing is the wrong thing to do in a situation like this.”

In practice, updating the software will take about one hour for each airplane and the training for each pilot takes around 30 minutes. However, while the amendments to the training procedures for the Max have been “provisionally approved” by regulators, the final package of software changes has yet to be certified by the Federal Aviation Administration and will be at the discretion individual regulators around the world who will determine if the changes are enough to return the 737 Max to service, according to the official.

Boeing is barred by international agreements from commenting on air safety investigations it is involved in until a final report is issued.

Related: 737 Max airlines take cover under the wing of a black swan

All of these changes to the 737 Max are happening in the middle of the two unfinished accident investigations, one of which is barely two weeks old, along with U.S. Congressional, Department of Transportation and Department of Justice inquiries into the certification of the 737 Max.

“We look back on accidents and we know that most accidents are the result of a chain of events and if any one of those links in that chain is broken then the accident doesn’t occur,” said the official. “We can go back and look at all of the links in the chain and ask questions about each of those links and try to understand what that link might tell us and what we might be able to do…before we get in the final report.”

Yet it remains unclear what additional findings, recommendations or required changes to the 737 Max will result, if any, while regulators move with extreme caution as they evaluate the aircraft. The Boeing official said after the crash of Lion Air 610 in Jakarta it had undertaken an internal audit of all of the 737 Max’s systems, with particular focus on the changes made from the earlier 737NG. “Those reviews continue and I’m sure they will continue for some time, but there was nothing that we’ve found at this point,” the official said.

But beyond its discreet evaluations and changes to the Max, the Boeing official broadly defended how the company develops aircraft. “Every time something happens, we learn from it,” the official said. “The process that we follow with the regulators and the process that we follow with the designs has continued to lead to safer and safer airplanes and safer and safer operations over time.

Related: The world pulls the Andon Cord on the 737 Max

“The regulators and the manufacturers around the world — all regulators, all manufacturers — work together to make sure that we’ve got an open and transparent system where whenever there’s not even an incident or an accident, but a learning that can come from anything, we incorporate that learning and we learn from it and we apply that to what we do next,” the official added.

Yet in the wake of the two crashes, the 737 Max remains grounded principally because of a divergence in global regulators working together, underscoring the severe uncertainty that still hangs over Boeing’s most important product and whether software and training changes will be sufficient to return the fleet to service.

Subscribe to TACSubscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention