This post is also available in:

![]() 简体中文 (Chinese (Simplified))

简体中文 (Chinese (Simplified))

Boeing, regulators and airlines are cautiously optimistic a conclusion to the grounding of the 737 Max is realistically — and finally — in sight. That sets the stage for the jet’s return to flying around September at the earliest. All of this is happening while simultaneously plotting further long-term safety improvements to the aircraft to assuage regulator concerns, including adding systems to the Max that were previously rejected during the jet’s initial development.

While a clear path to re-certification has emerged, those close to the process caution that there are still potential pitfalls that may extend the multinational process for re-approving the Boeing jet again for service after it was grounded in March 2019 after two crashes killed 346 people.

Related: FAA Administrator outlines final gantlet to return 737 Max to service

Two industry officials close to the recertification and re-entry of the 737 Max caution that a late June certification test flight is possible, but other milestones – including ones once planned for May – have not yet taken place. Bloomberg News first reported June 11 that Boeing and the Federal Aviation Administration could fly a formal certification sortie by month’s end.

Once the flight is complete, the FAA and other regulators will be able to hold the Joint Operations Evaluation Board (JOEB) review to determine the final training requirements for flying the 737 Max. FAA Administrator Steve Dickson outlined to The Air Current the final steps in February to returning the jet to service. In advance of the JOEB, which has not yet been scheduled, Boeing earlier this week sent an Operators Memo to 737 Max airlines outlining the draft training changes for pilots along with a service bulletin for modifying the jet’s wiring.

Related: Pilot procedure confusion adds new complication to Boeing 737 Max return

Crucially, Boeing and Collins Aerospace, which developed the flight control revisions for the Max, have completed revising the software package within the last two weeks. The pair was forced to tackle further changes to the software, including adjusting tolerances on sensors that were erroneously activating cockpit indications that the jet’s horizontal stabilizer was not properly configured. The companies are now in the last stages of “mopping up bits and pieces” of its protracted re-development that has stretched more than 20 months since the October 2018 crash of Lion Air 610 and Ethiopian Airlines 302 in March 2019, according to one industry official.

Subscribe to TACWhile the development is complete, Boeing and regulators will have to re-do earlier engineering simulator tests intended to validate the final functionality of the new software. The still-outstanding trials, known as 1301/1309 testing, denoting their subsections in the Federal Aviation Regulations, need to occur before the certification test flight can take place on the company’s 737 Max 7 test aircraft.

Further, it remains unclear what impact still-active COVID-19 travel restrictions will have on coordinating international regulators from Europe, Canada, China and Brazil for in-person evaluations of the updated 737 Max flight control software.

Boeing said in a statement that it “continues to work closely with the FAA and other global regulators on the process they have laid out for ungrounding the Max. Our team is focused on completing the software validation and the required technical documentation that will precede a certification flight.”

An FAA spokesman declined to comment.

European Coordination

One major factor still pacing the final approvals is gaining the blessing of the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) for Boeing’s changes. While the FAA is the arbiter for certifying U.S. aircraft designs and can advance unilaterally, FAA’s final clearance to Boeing is also being done in conjunction and agreement with European regulators. While the grounding of the Max threatened to unravel the global system of aircraft certification, the protracted process of re-certifying the 737 Max has brought EASA in tighter coordination with the FAA.

Related: 737 Max grounding threatens to unravel the aviation certification world order

EASA is conducting its own Integrated System Safety Analysis (ISSA) on the 737 Max and its new software, effectively applying a regulatory template intended for Airbus aircraft on top of Boeing. One of the industry officials said that both FAA and Boeing were “pretty concerned” that the ISSA process applied to the Max “won’t work.”

European regulators are now requiring the ISSA to be completed before they give the FAA their blessing. Fully validating Boeing’s revised software — before it is loaded on a test aircraft for certification in flight — also depends on the completion of the ISSA, according to one of the officials.

Two of the officials say the tension stems from deep philosophical differences underpinning Boeing and Airbus aircraft flight controls. Airbus aircraft, fly-by-wire and flown by a sidestick since the A320’s arrival in the 1980s, have relied on three Angle of Attack (AoA) sensors to validate accurate air data on the aircraft. Boeing’s 737 Max, not a fly-by-wire design (save for the spoilers), has been driven by two alternating sensors for air data on a mechanically-driven flight control system.

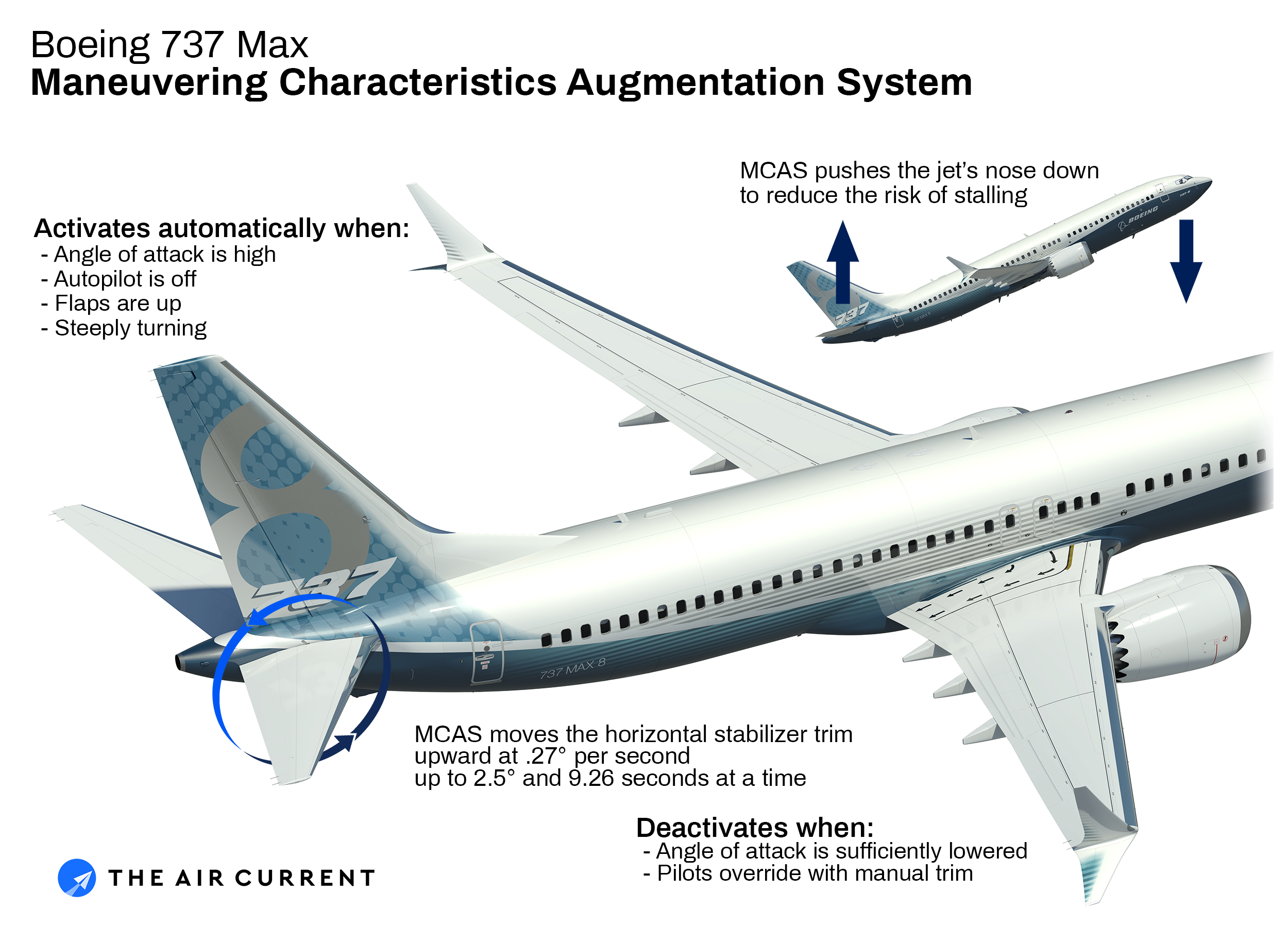

The new Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation Systems (MCAS) software at the center of the two crashes has been redesigned to rely on agreeing data from both of the Max’s two AoA sensors. In the case of the 737 Max crashes in October 2018 and March 2019, a single malfunctioning AoA sensor showed the aircraft to be stalling, causing the MCAS to repeatedly activate erroneously, eventually causing flight crews to lose control of the aircraft.

EASA executive director Patrick Ky told the European Parliament in September that the flight control improvements planned by Boeing had not elicited an “appropriate response to the Angle of Attack integrity issues.”

With the U.S. still ultimately the nation in charge of certifying Boeing designs, the Europeans are “treading as heavily as they can in an area where they have to tread lightly,” said one of the industry officials. The FAA and Boeing are “not going to convince the Europeans that fewer than three [AoA sensors] is acceptable” and the goal has been to “find an acceptable solution” to the AoA issue, the official added.

As it progresses through the ISSA, the solution to the dispute, however, is now clear. EASA’s requirements for the aircraft will spawn additional development work on the 737 Max after it returns to service. Specifically, one of the people familiar with the changes said Boeing, FAA and EASA agreed to implement a synthetic airspeed or equivalent system on the Max as a further source of data into the flight control computers. Committing to add the system later to the Max fleet, say industry officials, will ultimately allow European regulators to sign off on the near-term Boeing plans to return to service.

Related: Checklists come into focus as pace-setter for 737 Max return

In 2013, Boeing rejected a proposal to implement a synthetic airspeed system on the 737 Max early in its development out of concern it could “drastically alter” non-normal operations of the aircraft, according to emails published last year by U.S. Congressional investigators. Introducing the system as standard on the aircraft would have been costly and “would likely jeopardize the program directive” to not require any simulator training for Next Generation 737 crews cross-qualifying to the Max, a Boeing 737 technical pilot wrote in February 2013. Boeing is now recommending simulator training for all 737 pilots flying the Max.

Synthetic airspeed, first fielded on the 787, collects a variety of sensor data to avoid showing crew information that is known to be unreliable and improve stall protection.

One of the officials familiar with the planning said it could take “a couple years” to field the new synthetic airspeed changes but the regulators want action “sooner if possible.” One of the industry officials suggested that the final compliance with EASA’s requirements could include the addition of a third mechanical AoA sensor for the aircraft, a much more invasive hardware change that would need to be fielded across the full fleet of Max aircraft, now 800 and growing.

Write to Jon Ostrower at jon@theaircurrent.com

Subscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention