This post is also available in:

![]() 简体中文 (Chinese (Simplified))

简体中文 (Chinese (Simplified))

Plano, Texas — Boeing has completed development of the revised software for the 737 Max, but now it is in the hands of aviators to evaluate how best to take into account the human element.

In addition to the central question of the crisis — how and why did Boeing get the design of the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System so wrong — the assessment gets to the heart of another key aspect of the safety crisis facing the airplane, the interaction between human and machine. The answer is now a key pacing item in the jet’s return to service and has pushed the Federal Aviation Administration certification flight to validate the changes to the 737 Max into November at the earliest, according to industry and federal officials.

Boeing’s single-aisle jet has been grounded since March following twin crashes in Indonesia and Ethiopia five months apart that killed a total of 346 people.

Subscribe to TAC“There’s still several things to be resolved before [the FAA is] going to be ready to release the [airworthiness directive] to fly,” said Greg Bowen, Southwest Airline Pilots Association (SWAPA) Training & Standards Chair. “The FAA’s looking specifically at about six existing non-normal checklists that could end up being reordered or changed significantly. And the evaluation and review of those checklists in testing with pilots is still at least 30 days away if not further.” Bowen’s comments came on September 30 at the International Conference of Pilot Unions.

Southwest Airlines, the largest operator of the 737 and the Max, officially still envisions having the grounded airplane back in revenue service around the first week in January 2020, presuming a roughly mid-November airworthiness directive that would clear the airplane for service once again. But Jon Weaks, SWAPA’s President, said “We’re not confident in that at all” given the work left to be done by the FAA and by Southwest. Weaks anticipated it was more likely Southwest’s Max fleet would get back up and running by February or March 2020 in revenue service.

Related: The world pulls the Andon Cord on the 737 Max

Once the FAA clearance to fly is finalized, Southwest won’t begin revenue operations again until all of its approximately 9,900 pilots are fully trained following the official adoption of the new training regime for the Max. It’s also expected to take 45 to 60 days to prepare each of its 34 jets for service again given the 150 to 200 man hours of work required for each aircraft after their extended stay in storage. Southwest’s pilots have agreed to a minimum 30 day window after the directive is finalized for it to have completed the training prior to returning the jet to revenue service.

Related: 737 Max grounding tests Southwest’s relationship with Boeing

Separately, SWAPA on Monday filed a lawsuit against Boeing alleging it “deliberately misled” the pilots about the differences between the Next Generation and Max iterations of the 737. The union is seeking more than $100 million from Boeing for lost wages as a result of the grounding.

Additionally, American Airlines on Wednesday morning extended the removal of the 737 Max from its schedule through January 15. It had previously expected the aircraft back in service by January 6.

Separately, The Wall Street Journal and Reuters reported Tuesday that the European Aviation Safety Agency had concerns over the revised flight control computer software, potentially throwing the timeline for its approvals into question and whether or not it would quickly follow the FAA’s clearance.

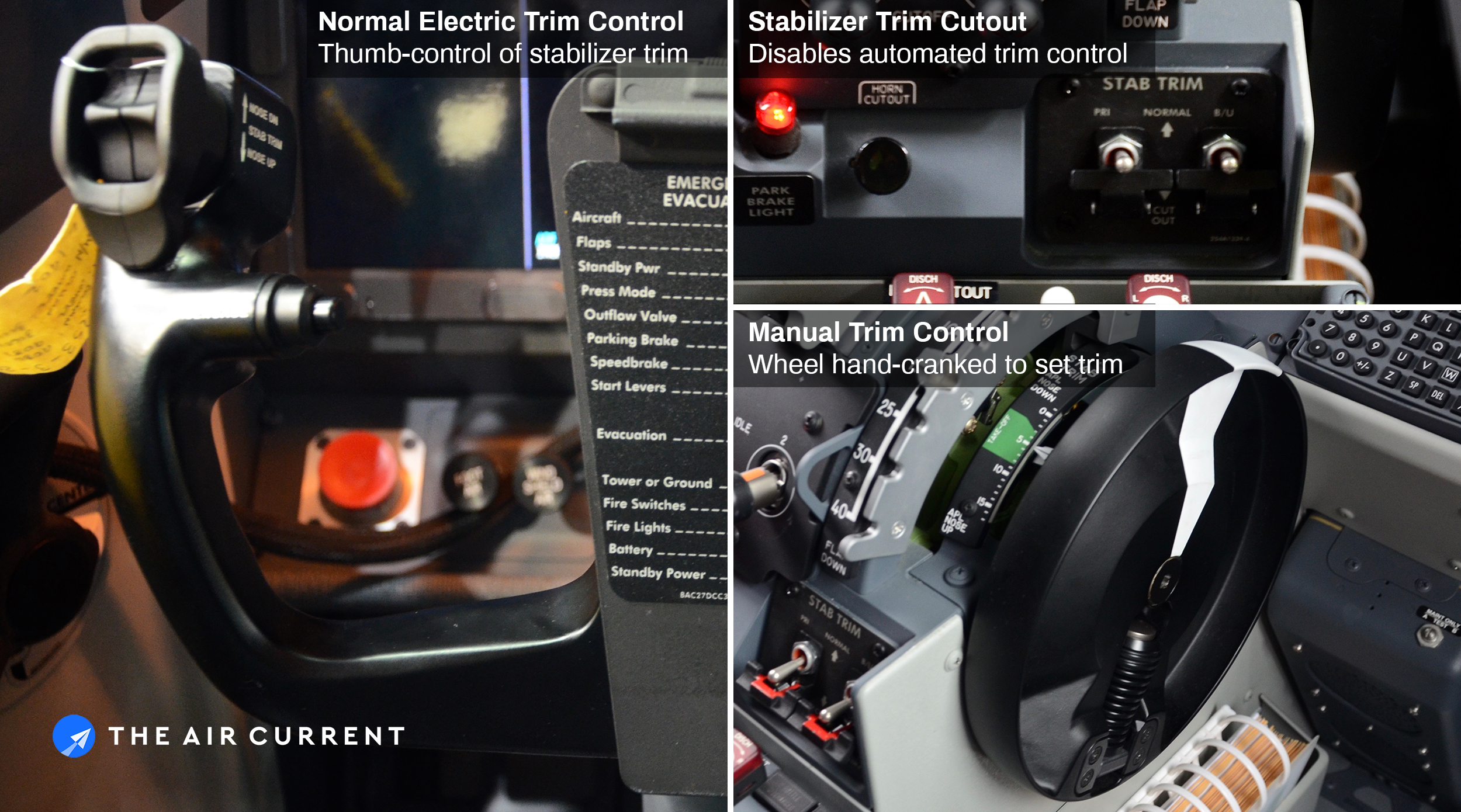

Much of the pacing for airlines also comes down to the varying set of customized standard operating procedures pilots use in commercial flying. Boeing provides a default set of procedures to airlines that operate 737s. Boeing’s procedures view the runaway stabilizer trim checklist, for example, as a memory item, by default.

Related: Vestigial design issue clouds 737 Max crash investigations

Not all airlines view it this way. Both American and Southwest today have switched to a Quick Reference Checklist (QRC) card system for the most urgent situations. Neither airline has the runaway stabilizer trim checklist as a memory item, for example, instead it is part of a quick reference card both use to fly the 737.

“I can’t say we’re in favor or not in favor” of making some of these checklists memory items “but we’re saying we want the FAA to realize that we’ve gone away from that to a QRC and now you want to change the game again based on the stab trim or a trim failure,“ said Allied Pilots Association Safety Chair for American Airlines, John DeLeeuw.

Official regulatory guidance from the FAA has discouraged the use of memory items as part of procedures. “Memory items should be avoided whenever possible,” according to a 2017 Advisory Circular from the U.S. aviation regulator. “If the procedure must include memory items, they should be clearly identified, emphasized in training, less than three items, and should not contain conditional decision steps.”

SWAPA’s Bowen pointed to the runaway stabilizer trim checklist in particular “as it currently exists” has the use of the stabilizer trim cutout switches at the “fourth or fifth” item on the checklist. “So one of the things we’re looking at is redesigning that checklist so that it follows the conscript of what people would normally be expected to remember or not,” he said.

After the crash of Lion Air 610 in October 2018, United Airlines made its runaway stabilizer trim checklist a memory item, according to two 737 Max rated pilots at the airline. “As part of our commitment to safety, United requires our pilots to memorize some procedures and utilizes a flight deck Quick Reference Checklist to reinforce those actions,” an airline spokesman said in a statement.

Related: Boeing details changes to MCAS and training for 737 Max

And there are other changes pending beyond just cockpit procedures, including revisions to the jet’s master minimum equipment list (MMEL). Today the Max can be dispatched with one failed flight control computer. “In the future you cannot,” said DeLeeuw, as part of the software changes coming for the aircraft that make the computers dependent on one another.

Boeing declined to comment to The Air Current, but has continued to maintain its fourth quarter expectation for the FAA’s airworthiness directive that will return the jet to service.

Related: FAA and Boeing initially disagreed on severity of 737 Max software glitch

The uncertainty around the revisions to flight deck quick response procedures comes from the work that is yet to be completed by the FAA’s Joint Operational Evaluation Board (JOEB), an assembled group of 737 Max line pilots from airlines around the world. They aren’t expected to meet until the end of October at the earliest to demonstrate and assess with the FAA the revised procedures for operating the Max. Several airlines expecting to be involved have not yet been contacted about a firm schedule for the evaluations.

The JOEB’s testing, which will look specifically at the ordering and priority of the checklists and memory items, will inform the overall recommendation by the Flight Standardization Board (FSB) as to the final training requirement for clearing pilots to fly the 737 Max again.

The issue is more complicated than a pro forma stamp of approval. One of the seven recommendations from the National Transportation Safety Board focused directly on the interaction between human and machine and recommends Boeing revisit its assumptions around “the effect of all possible flight deck alerts and indications on pilot recognition and response” and modify procedures to mitigate any risk.

Crucially, the JOEB’s work is pacing the most visible milestone for the Max’s return to service. The FAA certification flight with Boeing won’t be conducted until the JOEB assessment is complete and its analysis is shared with the FSB. And the final airworthiness directive from the FAA won’t be issued without the FSB’s work completed. The JOEB’s work pushes the certification flight into November at the earliest and any delay will push that out even further.

After the certification flight program is complete, Boeing will submit the final package of documents, including its system safety analysis to the FAA. Then, to review and prepare the final airworthiness directive, the FAA will “take as long as we need,” said a federal official.

Both the FSB recommendations and the final airworthiness directive by the FAA will require mandated comment periods before being officially adopted. But the federal official said that period may be less than the standard 30 days, given the ongoing level of involvement by a myriad of stakeholders.

However, politics and optics of a rushed process may interrupt any truncated comment period, according to others close to the review.

Write to Jon Ostrower at jon@theaircurrent.com