This post is also available in:

![]() 简体中文 (Chinese (Simplified))

简体中文 (Chinese (Simplified))

Updated November 17 explaining MCAS and electric trim override operation.

When Boeing set out to develop the 737 Max, engineers had to find a way to fit a much larger and more-fuel efficient engine under the wing of the single-aisle jet’s notoriously low-riding landing gear. By moving the engine slightly forward and higher up and extending the nose landing gear by eight inches, Boeing eked another 14% improvement in fuel consumption out of the continually tweaked airliner.

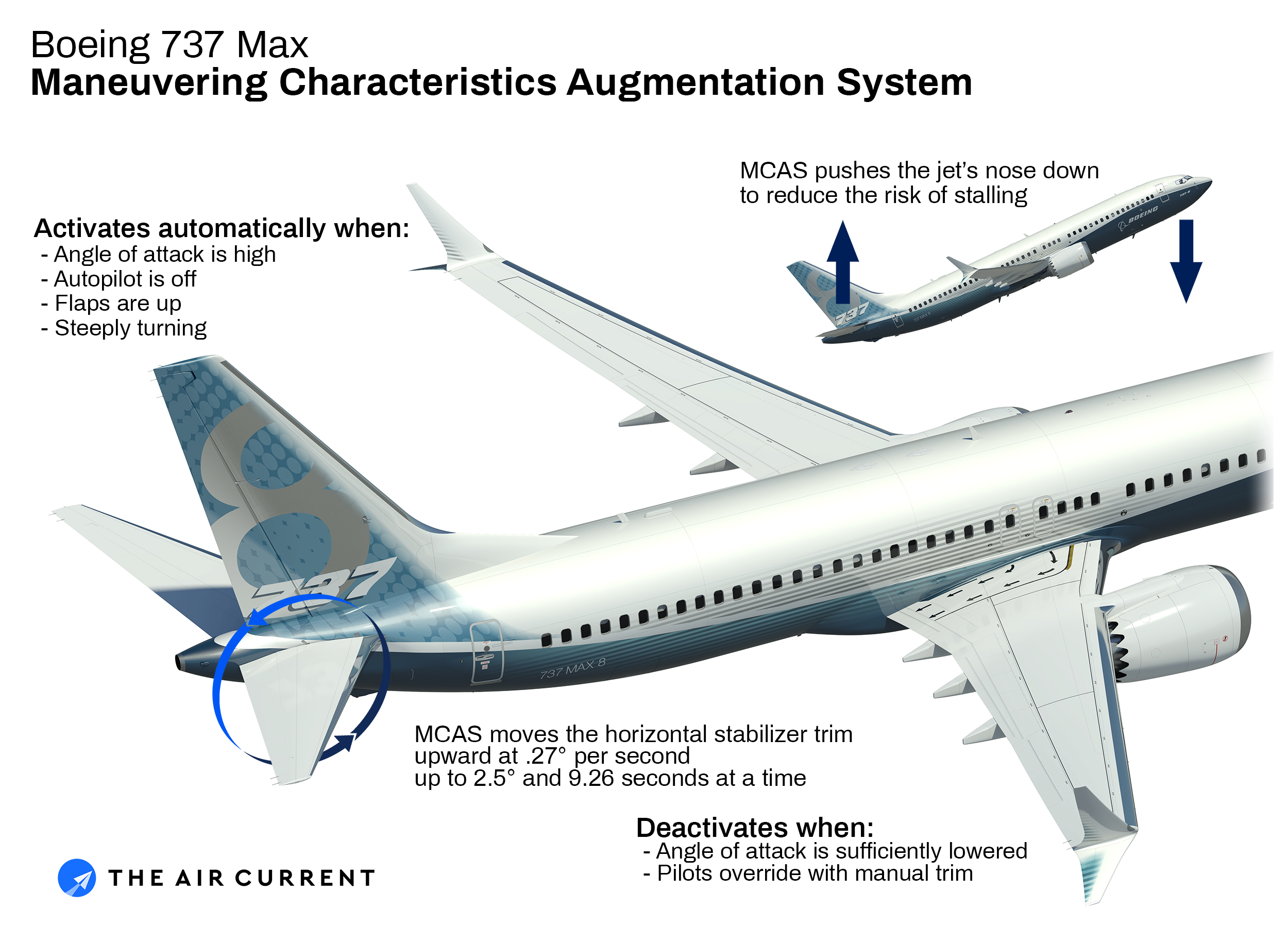

That changed, ever so slightly, how the jet handled in certain situations. The relocated engines and their refined nacelle shape1 caused an upward pitching moment — in essence, the Max’s nose was getting nudged skyward. Boeing quietly added a new system “to compensate for some unique aircraft handling characteristics during it’s (sic) Part 25 certification” and help pilots bring the nose down in the event the jet’s angle of attack drifted too high when flying manually, putting the aircraft at risk of stalling, according to a series of questions and answers provided to pilots at Southwest Airlines, the largest 737 Max operator reviewed by The Air Current.

The Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) was designed to address this, according to Boeing engineers and pilots briefed on the system, now at the center of the inquiry into the crash of Lion Air 610, a brand new Boeing 737 Max 8. MCAS is “activated without pilot input” and “commands nose down stabilizer to enhance pitch characteristics during step turns with elevated load factors and during flaps up flight at airspeeds approaching stall.”

“Its sole function is to trim the stabilizer nose down,” according to the system’s description to pilots, who were learning about it for the first time this week.

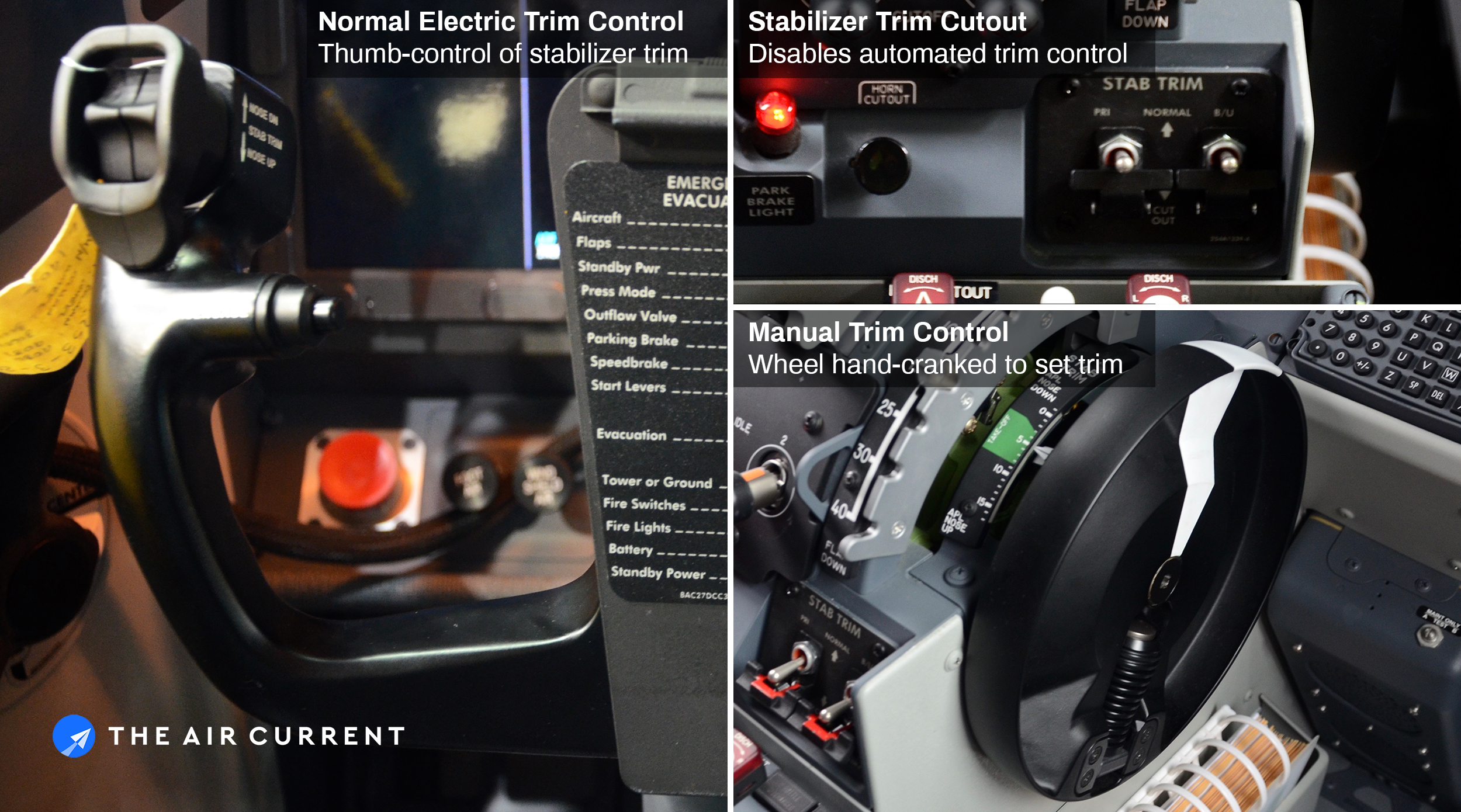

The system activates when the sensed Angle of Attack (AOA) “exceeds a threshold based on airspeed and altitude.” That tilts the 737 Max’s horizontal stabilizer upward at a rate of .27 degrees per second for a total travel of 2.5 degrees in just under 10 seconds. How much the stabilizer moves depends on Mach number. At higher Mach the stabilizer moves less, at slower speeds it moves more. The trim system under MCAS is not stopped by simply moving the control yoke.

Related: Boeing issues 737 Max fleet bulletin on AoA warning after Lion Air crash

If the Max is at a high AoA — or its sensors erroneously believe that it is — “the MCAS function commands another incremental stabilizer nose down command.” The system can be deactivated if pilots trim the aircraft manually to override the MCAS’s attempt to automatically pitch the jet’s nose down.

Boeing said in a statement that it is “taking every measure to fully understand all aspects of this incident, working closely with the investigating team and all regulatory authorities involved. We are confident in the safety of the 737 MAX. Safety remains our top priority and is a core value for everyone at Boeing.

“While we can’t discuss specifics of an on-going investigation, we have provided two updates for our operators around the world that re-emphasize existing procedures for these situations.”

Subscribe to TACThe existence of the MCAS system caught pilots and their labor unions off guard, intensifying the scrutiny on the aircraft in the wake of the October 29 crash in Indonesia that killed everyone aboard. The system isn’t mentioned in the flight crew operations manual (FCOM) that governs the master description of the aircraft for pilots and is the basis for Southwest’s airline documentation and training.

The Southwest Q&A asks Why?

“Since it operates in situations where the aircraft is under relatively high g load and near stall, a pilot should never see the operation of MCAS. As such, Boeing did not include an MCAS description in its FCOM.” The explainer continues: “In this case, MCAS will trim nose as designed to assist the pilot during recovery, likely going unnoticed by the pilot.”

There is another explanation, according to a Tuesday report in The Wall Street Journal: “One high-ranking Boeing official said the company had decided against disclosing more details to cockpit crews due to concerns about inundating average pilots with too much information — and significantly more technical data — than they needed or could digest.”

Subscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention