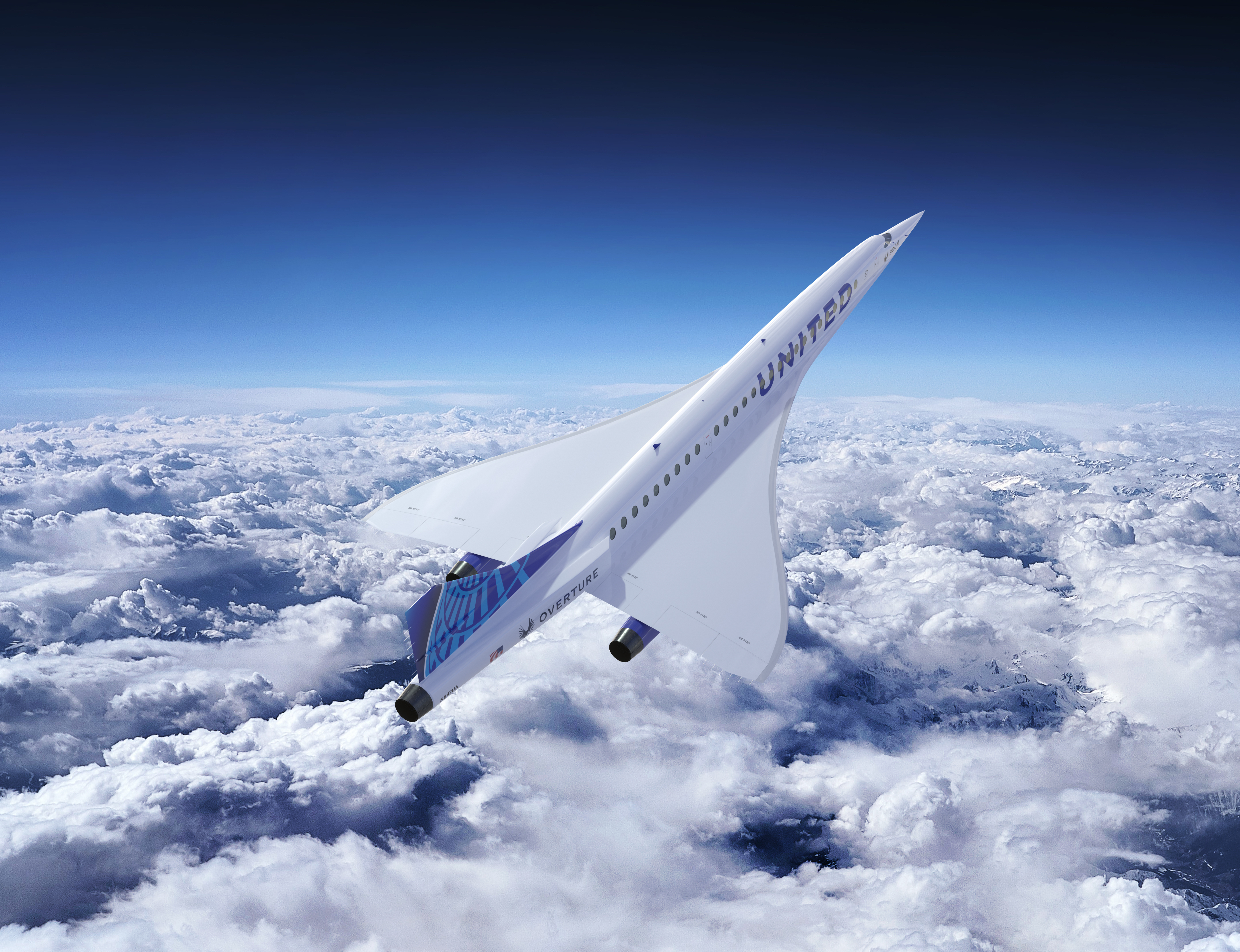

United and Boom Supersonic announced a commercial agreement for the startup’s 88-passenger airliner, Overture, ready for 2029. The agreement is the culmination of a year of discussions between United and Boom and would put 15 aircraft in its fleet — assuming it achieves Federal Aviation Administration certification — and gives the airline options for 35 more.

Related: Out of money, Aerion’s supersonic pursuit is at its end

“It is a real aircraft that we are pursuing,” said Mike Leskinen, United’s head of corporate development and architect of the agreement. Leskinen briefed The Air Current last week on why United wants a supersonic aircraft and why the airline wants to be lead operator for the first time since it launched the 777 with Boeing in October 1990.

“This is an order, but to call it a firm order is inaccurate,” said Leskinen, who notes that money has changed hands for deposits and there are financial protections for United built into the agreement. “They have to deliver. And we’ve got a number of years to deliver on that. We’re going to work closely with them to help.” Boom wants to test fly Overture in 2026.

Read: Electric, supersonic startups lay down their industrial roots

With eight years to go before entry into service, United is lending its considerable operational and technical expertise and its credibility to Boom. United is among a cadre of fewer than 10 airlines on the planet with the technical and operational know-how to evaluate a new commercial aircraft. Its blue chip status carries enormous weight and has historically acted as a market validator for other airlines.

“It also is as unique a product as we’ve had the opportunity to look at for mainline flying ever. And so it requires looking a little further down the road,” said Leskinen, who sees “zero, zero, zero, absolutely zero” risk in attaching United to startup aircraft manufacturers. “We’re going to make good, smart bets.”

Boom is United’s second big bet on the future of transportation. In February, it backed an effort by eVTOL startup Archer to cultivate intracity flights for delivering five passengers at a time to its hubs. Archer next week will unveil its first all-electric Maker aircraft in Los Angeles.

If a project isn’t working “we’re going to be smart about it and not stick our head in the sand,” said Leskinen. “I won’t apologize at all. If you don’t occasionally fall, you’re not trying. I wouldn’t even view it as a failure. We are pushing the boundaries of what we can do here in commercial aviation.”

The commitment from United is an unequivocal lift for Boom. The Denver-based startup still has a considerable way to go before a supersonic revival can become reality. Boom came out of stealth mode in 2016 with a loose commitment from Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Group and has since raised $270 million, including $10 million from Japan Airlines which also has an option (but no agreement) for 20 Overture aircraft.

Blake Scholl, Boom’s founder spoke with TAC on Tuesday about the agreement with United. Scholl has estimated that going from standing still in 2014 to a full-fledged aircraft manufacturer will take an estimated $8 billion. And that’s probably conservative. Scholl hinted that the company is in talks to merge with a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) — a tool used by other aerospace entrants like Joby Aviation and Archer — to go public and raise funds for Overture’s development and industrialization. “I can’t comment on things that aren’t public. So I can’t say too much about that. There are a number of very high quality investors that are very excited to support Boom.”

“Our belief that the [capital] markets are open — they’ll be able to raise funds — was a big part of our confidence here,” said Leskinen.

There’s still much undefined about the final concept that United is purchasing – most notably, what engine will be chosen to power the Overture. Boom has been working on two concepts with Rolls-Royce, which has been sent reeling due to the pandemic. Each is an adaptation of the engine maker’s latest-generation Trent 1000 and Trent XWB cores flying on the 787 and A350, respectively.

Read: Coronavirus shreds the engine maker business model

“We’re very close to making those decisions,” said Scholl, who noted there’s still room for another manufacturer to make a pitch. Originally envisioning Mach 2.2 for Overture, the combination of regulatory noise requirements and resulting fan size led Boom to refine its cruising speed to Mach 1.7 at 60,000 feet, effectively twice as fast as its Boeing 787s, the fastest aircraft in United’s fleet today. Boom expects a firm configuration by the end of 2021.

“There’s some risk, there’s no question about it,” said Leskinen of the engine. “I am happy as the head of corporate development at United to buy that risk. And if there was some delay over that, we’ll work through it.”

Supersonic realities

What United will quickly find is that the practical reality of supersonic operations are dictated by a tricky balance between immovable geography and unyielding time zones. The airline believes that its coastal hubs in Newark, N.J. and San Francisco are ideal for overwater supersonic operations to London (3.5 hours) and Tokyo (6 hours), respectively.

United is approaching this process of cultivating a startup plane maker with its eyes open. There are still technical operational questions to resolve for United, not the least of which is how to fly between Tokyo and San Francisco without a time-consuming fuel stop in Anchorage. Tokyo’s downtown Haneda airport is 234 nautical miles shy of Boom’s advertised 4,250 nautical mile non-stop range from SFO.

“I think that it’s an expensive aircraft and so at least in the near term, you’re gonna want to fly it out of hubs like New York and San Francisco — not Dallas or Charlotte, it won’t work there,” said Leskinen. A supersonic transport’s premium passengers will most likely begin and end their journey in each mega-city. “The breadth of the market to and from London and New York is massive.” (Three times larger than 2003 when Concorde stopped flying). Connecting to a supersonic flight from another destination quickly nullifies the benefit — even at twice the speed — when adding a layover.

In its heyday, westbound legs to the United States on Concorde were more popular than the return (about 20 percentage points difference). The benefit was to arrive in New York one hour before leaving London, two if flying from Paris. The second daily eastbound return to London left New York at 1:45pm — arriving at Heathrow at 10:25 pm — making a subsonic evening return with time to sleep preferable after a full day’s work in New York and time to be back at your desk the following morning.

Related: JetBlue doesn’t think flying to London is all that radical

Across the Pacific is a longer-term goal for United. With a six and a half hour flight to a destination with a 16-hour time difference “you do come up on questions of like ‘it’s so fast, can you really optimally use it?’ because you want to use the optimal time windows,” said Leskinen. “It’s not as simple as getting twice the utilization because it’s twice as fast.”

At least at first, said Leskinen, “We need it to work New York to Western Europe and nothing more.”

Can fast still be green?

A supersonic future without an adequate supply of sustainable fuel isn’t possible. And whether Boom’s Overture becomes a reality or not, United is using brute commercial force — and marketing — to kickstart demand for the plentiful availability of sustainable aviation fuels (SAF). Leskinen said a “big part of the value proposition that United brings to Boom, is that objective of partnering in bringing more SAF to market.”

“I think there’s a growing recognition that SAF is the only way to decarbonize long haul flight,” said Scholl, recognizing hybrid and electric technologies aren’t ready for those applications. “One of the biggest chicken and egg problems with SAF has been, okay, is there a market? If there’s not a market, there’s no producer, there’s no investor in that producer. If you show the market’s there, then the supply follows,” said Scholl. Overture will be certified out of the box for use with SAF.

Read: Understanding the industry-transforming dynamics behind Airbus’s hydrogen Moonshot

United’s chief executive, Scott Kirby, has placed a heavy focus on environmental sustainability for the carrier. United in April said it planned to buy enough SAF in 2021 to fly over 220 million passenger miles. It’s a drop in the bucket for an airline like United, but it’s a start on its goal of carbon neutral flying by 2050. The airline flew more than 60 billion passenger miles in the first quarter of 2020 alone.

SAF, blended from synthetic or biofuel sources, promises to reduce a flight’s carbon footprint by between 40% (beef tallow) and 80% (used cooking oil) depending on the source material, according to Dan Rutherford of the International Council on Clean Transportation. Rutherford notes that there are still outstanding certification questions, namely whether or not different types of SAF can refill the same tank on subsequent flights.

Scholl estimates that currently committed SAF projects will cover Overture’s needs late in the decade. “It’s enough for supersonic. It’s not enough for the whole industry,” he said.

At twice as fast as its subsonic fleet, Boom’s Overture may burn as much as three times the fuel per passenger, according to a person directly familiar with United’s preliminary review of Overture’s conceptual operating economics. There’s significant nuance in that estimate, including the side-by-side comparison of placing United’s lie flat Polaris business class seat — designed for extended duration flying — into Overture.

Read: In Hamburg, Airbus passes last embers of A380 torch to A321XLR

Scholl disputes that claim and is insistent that Overture will cost the same to operate as a business class seat on a state-of-the-art subsonic airliner, as a carved out share of the aircraft’s operations. “It’s like you took the front cabin of a 787 and made it go really fast,” said Scholl. It’s a murky comparison, as that cost calculation depends on the other classes of travel and all of the other costs to operate an aircraft designed for flying nearly 8,000 nautical miles with 270 passengers aboard. Business class, of course, shares the use of wings and engines with economy class.

Scholl believes that the Overture’s operating costs will still allow an airline like United to command a premium fare. Even Leskinen acknowledges that Overture will have to burn more fuel per seat than the latest subsonic long-range offerings from Airbus and Boeing. “I mean, you put it up against 787, which is not that differently priced, by the way. Overture’s got a lot less seats and burns more fuel.”

Can United get paid for speed?

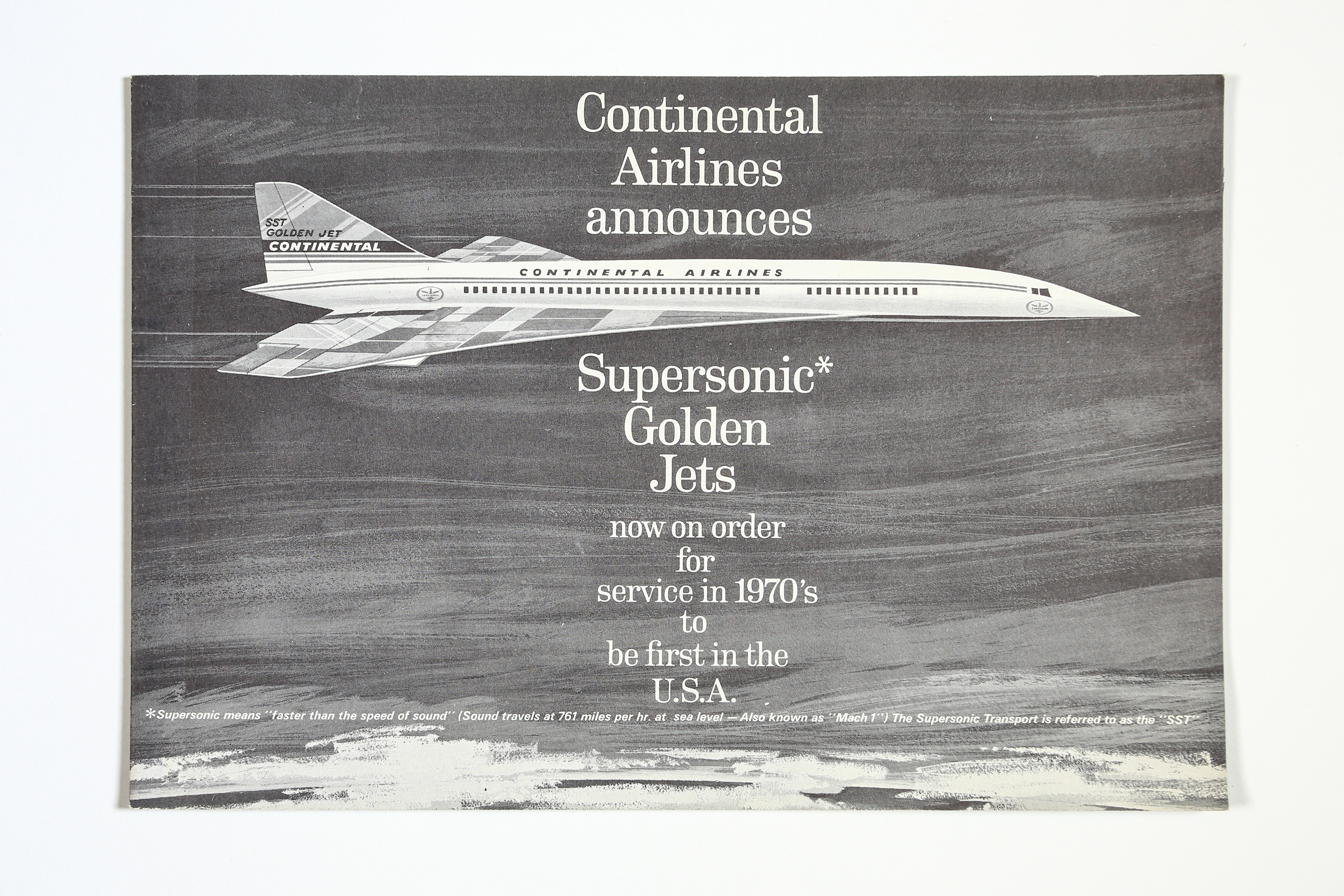

While United believes the Overture concept benefits from the company’s claim of a projected 75% improvement in operating cost against Concorde, an aircraft that first flew in 1969, this airplane is not aimed at democratizing supersonic travel.

“This isn’t about CASM,” said Leskinen of the conceptual cost per seat cost to fly Overture. “This is about profits and you’ve got to put it in a premium RASM. I mean, if it’s about CASM…we’re wasting our time talking about it. It’s going to be more expensive.”

Concorde definitively came with a premium fare. In June 1996, a roundtrip fully-refundable supersonic journey between the U.S. and the U.K. cost £5,774 (about £11,100 or $15,700 adjusted to inflation for 2020) according to The Concorde Story, written by Christopher Orlebar, who flew the aircraft for British Airways and retired from the airline in 2000. The price fell to £4,772 with a £70 cancellation fee. The same subsonic journey was £4,314 in First Class, giving BA a 34% premium for speed across the Atlantic.

Does the economic reasoning behind Concorde hold weight in 2021 – can airlines get paid for the speed? Boeing in the early 2000s came up with an answer: no. Its short-lived Mach .98 Sonic Cruiser experiment gave way to the eventual 787. Airlines wanted at least 15% better efficiency, not 15% faster flying.

There were economic benefits to speed. On some city pairs a faster aircraft could fly with one less relief pilot, whereas three crew would be needed on the same subsonic journey. Yet, the pursuit of neutral costs versus a 767 was only part of the equation. Boeing was unconvinced that airline behavior wouldn’t ultimately leave the Sonic Cruiser as a net loser for operators.

“There was also concern about whether we have, as an industry, the discipline to harvest the value [of speed] or would it all go through competitive forces to ticket price,” said Mike Sinnett, Boeing’s Vice President of Airplane Development in a 2015 interview.

Read: Tracking 30 years of falling airline ticket prices

“But then the concern was competitive forces would lower prices on other routes and people couldn’t justify the difference. They’d go fly those. And then the Sonic Cruiser would have to drop its prices again and pretty soon you’re back to where you were or you’ve taken revenue out of a city pair,“ said Sinnett. Ultimately Boeing determined it was likely a net negative for airlines burning more fuel and also more expensive to build.

United is counting on a first-mover advantage, especially if there’s a slow production ramp up. If it eventually meets competitors with their own supersonic aircraft across the North Atlantic, Leskinen sees that dynamic as a win, “Because it validates the aircraft. It means that the supply chain is healthy, that we’ll be able to get maintenance, that everyone can work together to get SAF.” If it all unfolds, “This will have been one of the smartest deals we’ve ever done.”

An earlier version of this article said Boom’s target for Overture’s range was 4,500 nautical miles, according to United’s understanding of the aircraft’s specification. Boom’s brochure range for Overture is 4,250 nautical miles.

Write to Jon Ostrower at jon@theaircurrent.com

Subscribe to TACSubscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention