Last week, the U.S. Department of Justice reached a deferred prosecution agreement with Boeing over the conduct of two of its technical pilots, stemming from the company’s actions before and after the 2018 and 2019 crashes of Lion Air 610 and Ethiopian 302.

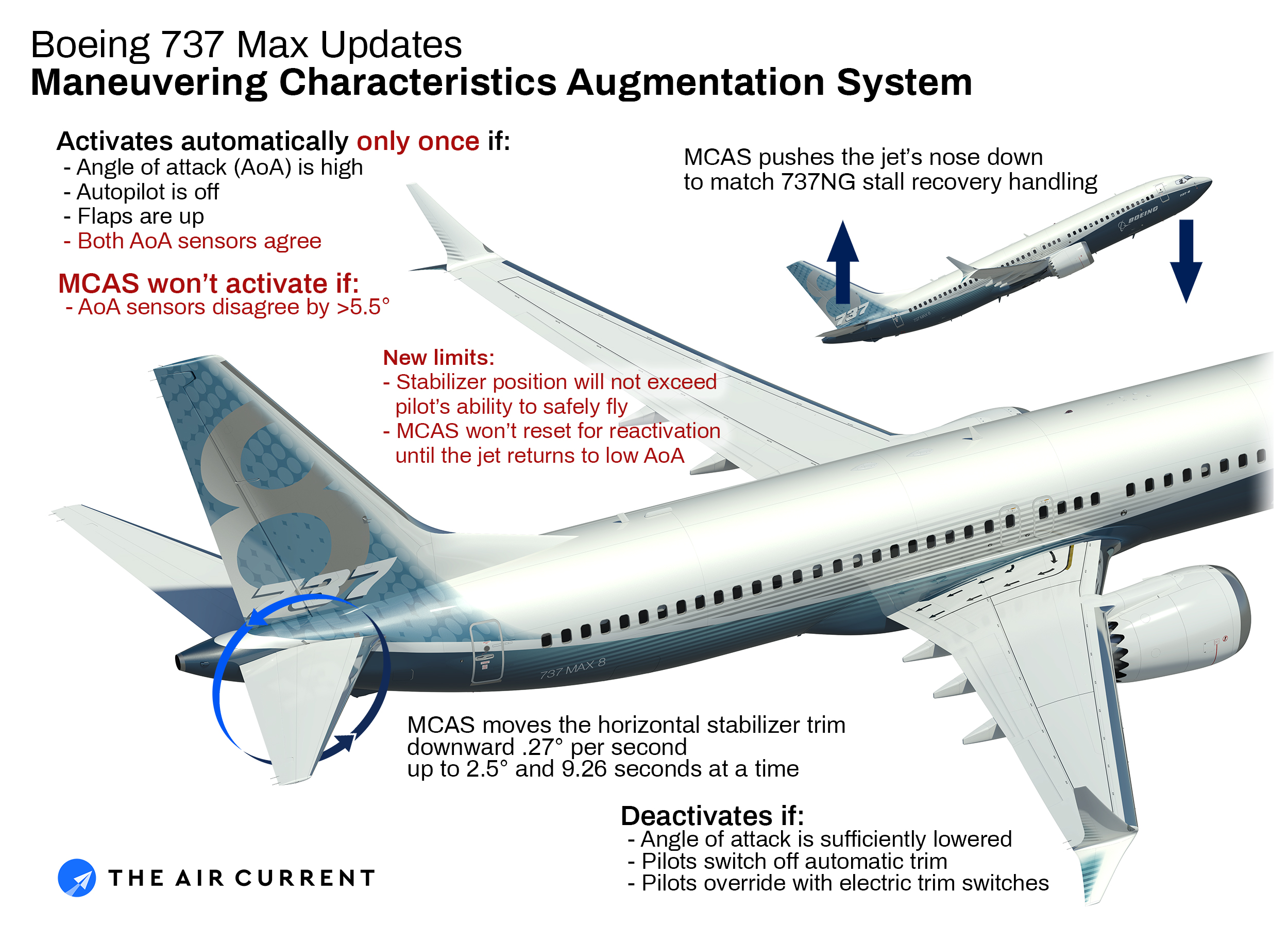

Mark Forkner and colleague Patrik Gustavsson have been near the center of the legal, regulatory and Congressional inquiries about Boeing’s alleged willful non-disclosure to the Federal Aviation Administration regarding details surrounding the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) on the 737 Max. That system erroneously activated on both flights, triggering a chain of events that ended with the death of 346 people.

Related: What is the Boeing 737 Max Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System?

“Boeing’s employees chose the path of profit over candor by concealing material information from the FAA concerning the operation of its 737 Max airplane and engaging in an effort to cover up their deception,” wrote Acting Assistant Attorney General David P. Burns of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division.

Boeing has agreed to pay $243.6 million in criminal penalties, plus $500 million more to a crash-victim beneficiaries fund. A separate $1.77 billion compensation payment to Max customers has already been paid and factored into the company’s earnings, bringing the total criminal penalty to more than $2.5 billion.

This article won a 2021 Aerospace Media Award. Subscribe to TACYet, the agreement focuses narrowly on the conduct of the two Boeing technical pilots. The DOJ noted in court filings that “the misconduct was neither pervasive across the organization, nor undertaken by a large number of employees, nor facilitated by senior management.”

The agreement with the DOJ is a partial conclusion to the 20-month long grounding that followed the second Max crash and resulted in an overhaul of flight control software and training programs for the aircraft. The 737 Max re-entered service on Dec. 9 with Brazil’s GOL Linhas Aereas and in the U.S. with American Airlines on Dec. 29.

While the DOJ exonerates Boeing in any kind of systemic way, Forkner and his flippant internal communications have been under the harshest spotlight, the chief technical pilot was tasked with executing a core objective of the 737 Max program. “I want to stress the importance of holding firm that there will not be any type of simulator training required to transition from 737 NG to MAX,” wrote Forkner to his colleagues just weeks after the aircraft had been certified by the FAA in March 2017. “Boeing will not allow that to happen. We’ll go face to face with any regulator who tries to make that a requirement.”

Related: New document in 737 Max investigation points to chaos, pressure in MCAS development

The FAA the previous August had granted provisional approval to limit transition training for the 737 Max to a brief computer-based course. The training wouldn’t require a simulator, principally because of the aircraft’s similarities between generations.

The Air Current has reassembled more than a decade’s worth of reporting on the origins of this program directive to limit training that stemmed not simply from a dollars and cents calculation for airlines, but a strategic analysis that was central in steering Boeing away from a clean sheet design to replace the 737 in favor of the Max. The result was intense pressure on Boeing staff to deliver limited training, according to interviews with executives and engineers over the past two years and a review of copious internal documents related to the system’s development.

This postscript to the most severe safety crisis in Boeing’s history outlines the moments, milestones and catastrophic missteps that led to MCAS’s fateful implementation. Yet, the saga of MCAS, which still lives now-modified inside the Max flight control computers, concludes with one haunting realization. The system may not have been necessary at all, according to FAA Administrator Steve Dickson, a sentiment seemingly shared by European regulators, too.

Boeing did not respond to repeated requests for comment both directly through its senior communications leadership, as well as through a strategic communications firm representing the company.

Don’t unlock the market

The strategic necessity of MCAS pre-dated the hasty July 2011 go-ahead decision to pursue the Max when American Airlines split a record single-aisle jet deal between Boeing and Airbus. In the preceding year, Boeing wrestled with a decision between launching a clean sheet replacement for the 737 or an engine-driven upgrade that would eventually become the 737 Max. Boeing realized that an all-new single-aisle might do irreparable short and long-term damage in its fight with Airbus.

Related: The world pulls the Andon Cord on the 737 Max

Yet, at the root of the debate was a sharp realization, according to Boeing strategists who conducted an internal study at the time. Without a tight tether to 737 and its existing infrastructure, a new airplane would “unlock” its loyal 737 NG customer base to purchase Airbus A320neos.

Boeing knew something needed to be done responding to the A320neo. But in deciding its path forward, the company had to disincentivize airlines from switching away from its wildly successful Next Generation 737 to Airbus. With its enormous group of 737 operators, the cost to its existing operators had to remain prohibitively high or it had to have a production system ready to deliver aircraft at breakneck speed. The production system wasn’t ready.

In the hypothetical consideration of buying a clean sheet Boeing airplane or buying from Airbus, the company concluded that the costs to airlines to switch were negated. With commonality from the 737 NG broken, even if the airline stayed with Boeing on a notional 797, customers would be effectively “switching” to an all-new model — and with it would come the high cost of adding a new fleet type. The strategic directive was simple: Keep your customers locked in from looking elsewhere. A new airplane, with its $10 billion to $15 billion price tag, strategists concluded, was ultimately a recipe for losing as much as 30% of its market share.

Boeing’s head of business development told FlightBlogger in a June 2011 interview just prior to the Max’s go-ahead that Boeing “would not do a plan that has us losing market share. We would have a plan that would have us gaining market share. That means that we have to understand with confidence how to keep our existing customer base and grow it.”

“Every new buzzword represents a company and airline cost via changed manuals, changed training, changed maintenance manuals,” concluded Boeing in preparation for a 2013 meeting to strategize how to minimize MCAS to regulators and customers. And every added cost on the Max brought the A320neo closer. “Airbus is throwing money at the flip,” wrote a Boeing staffer in 2017, trying to win over its 737 customer base.

So, with the Max its decided course, limiting the cost of training to Level-B, a tablet application and not spending time in a simulator, became a key differentiator and something Boeing had to tightly control. If Airbus would re-engine the A320, so would Boeing for the 737. If Airbus only required computer-based training for the Neo, so would Boeing on the Max. It would become a program directive — a core tenet of designing the aircraft that had to be achieved. They were Boeing’s “ground rules” for the 737 Max.

The directive drove the program

Even before the 737 Max flew in January 2016, Boeing knew that the more fuel-efficient and larger CFM International Leap-1B engines would create an upward pitching moment that made its stall characteristics differ from the earlier Next Generation 737. With many operators slated to fly both 737 generations side-by-side in their fleets, pilots would be flying an NG in the morning and the Max in the afternoon.

In practice, what this meant is that as the airplane approaches a stall — the point where airflow nears separation from the wings — the force the pilot exerts on the controls did not consistently increase with angle of attack. “The handling gets to be more like a moving van than a sports car,” said former veteran Boeing flight controls engineer Peter Lemme.

To meet certification standards, Boeing devised a system to account for that difference to maintain continuity between both 737 generations so pilots wouldn’t have to handle each jet differently.

That system was MCAS. With the program directive to limit training for 737 NG pilots to Level B in place, Boeing actively downplayed MCAS as not a new or novel system for the Max, but an extension of the existing 737 NG’s Speed Trim System that assists when hand-flying the aircraft.

Read: Checklists come into focus as pace-setter for 737 Max return

The MCAS control law is intended to correct those differences in stall handling between the Max and the earlier generations of the 737 when the flaps are up, the autopilot is off, and the plane is flying at high angle of attack. Using control laws to resolve aircraft issues was common. 737 Max Chief Project Engineer, Michael Teal, had just wrapped up a stint as chief project engineer for the 747-8 where a one-inch wingtip flutter had been solved with software and its fly-by-wire aileron.

On May 4, 2013, Teal, sent an email to Boeing managers “indicating ‘concerns’ about the addition of MCAS to the flight controls system and its impact on Boeing’s ability to obtain Level B (non-simulator) pilot differences training for 737 Max pilots,” according to documents revealed by the U.S. House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee investigation that was completed in September.

Just about a month later, Boeing staff met to discuss a solution. “If we emphasize MCAS is a new function there may be a greater certification and training impact,” according to the log of the June 7, 2013 meeting’s minutes.

So the fateful decision was made to “treat MCAS as an addition to the existing Speed Trim.” “Externally” Boeing would “communicate it as an addition to the Speed Trim” and “internally continue using the acronym MCAS.” The final item on the meeting’s minutes concluded Boeing must “make sure” that European aviation regulators understand that “MCAS is an addition to Speed Trim.”

A few hours later, an unidentified Boeing staffer wrote that its company-employed FAA delegates were in agreement (“concurrence was provided,” the person wrote.) with the company view. “This will allow us to maintain the MCAS nomenclature while not driving additional work due to training impacts and maintenance manual expansions.”

The copy and paste penalty

During the course of its development, project staff heard repeatedly that if they didn’t achieve the Level-B directive it could derail the program and Boeing could be on the hook for (at least) $1 million for each 737 Max it was selling to Southwest, its largest customer.

“There was great pressure to limit the transition training for a Next Gen pilot to the Max to a certain low level (no simulator time required) and every time something new came up that might push the training level up to require some simulator time there was huge pushback,” one retired Boeing engineer who worked on the Max program told TAC. “So that constraint was driving decisions as much as potential unravelling of the certification basis did.”

Yet, the oft-discussed per-plane penalty provision in Southwest’s contract for each 737 Max aircraft if simulator training was required was actually a vestige of an earlier deal. There wasn’t a lot of thought given to it, according to a senior Southwest executive, but it would have profound cultural consequences on the development of the Max.

Related: 737 Max grounding tests Southwest’s relationship with Boeing

The contract provision was “copied and pasted” as part of an earlier contract template that spelled out transition requirements between 737 variants. “It was essentially the same that we had for the NG” from the 737 Classic, geared around preserving the common type rating across generations. No simulator training1 was required during the 1997 737-700 service entry, according to three veteran Southwest pilots.

The penalty was minuscule, said the executive, and any required simulator training cost to maintain commonality between the NG and the Max was “not even a rounding error” compared to the cost to Boeing if the Max had been certified in a way that would’ve split Southwest’s fleet.

Related: How Southwest has adapted to live without the 737 Max

In a statement, a spokesman for Southwest declined “for competitive reasons” to delve into the specifics of its contracts. However, the company said that “we utilized a very standard agreement with Boeing regarding the delivery of the Max aircraft. We have customary language in each of our delivery contracts to hold parties accountable to previously determined benefits of launching a new aircraft type.

“The purchase of an aircraft is a significant investment, and guarantees for various items (fuel, maintenance, performance) have been incorporated into every contract from the 737-300s to the 737 NGs, this is a standard practice that is not new to us, the industry or the Max aircraft.”

Today, Southwest is training more than 160 pilots each day through its nine Max simulators in preparation for the jet’s return to service later in the first quarter.

The MCAS expansion

Five weeks after the 737 Max 8 first flew in January 2016, Boeing ran into a bigger challenge with certifying the aircraft’s handling than it had first anticipated when it analyzed the design in the wind tunnel years before.

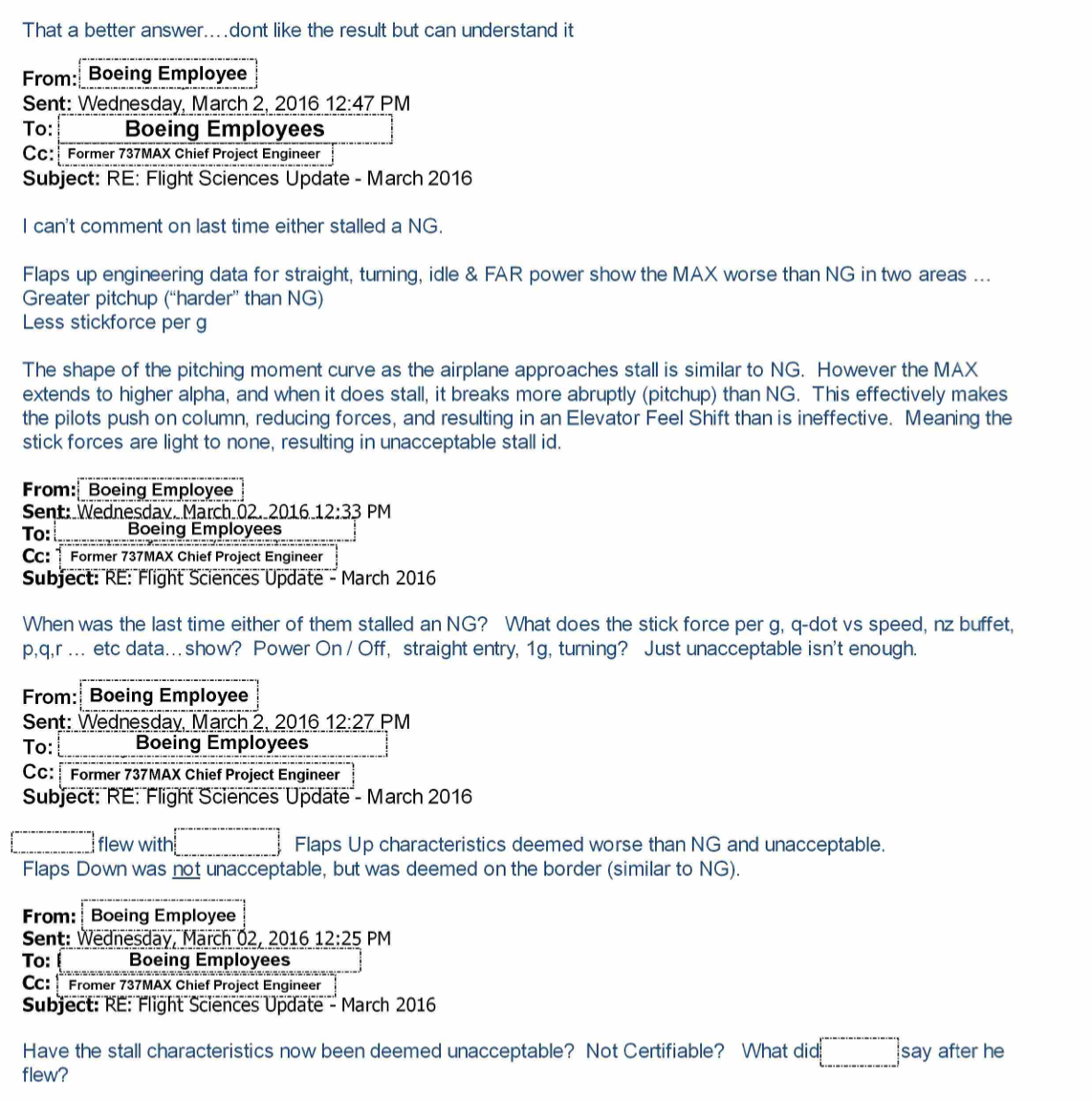

Early test flights showed that the Max approached stalling similar to that of the NG, but with flaps up, its flying characteristics were “deemed worse than the NG and unacceptable,” according to a March 2, 2016 email exchange that included Teal from an unidentified Boeing staffer.

With its flaps up and flying with its wings level, engineering data showed that “when [the Max] does stall, it breaks more abruptly (pitchup) than the NG,” wrote the Boeing staffer. “This effectively makes the pilots push on the column, reducing forces…meaning the stick forces are light to none, resulting in unacceptable stall id.”

Related: Pilot procedure confusion adds new complication to Boeing 737 Max return

By the end of March, program leadership approved expanding MCAS to cover the lower speed triggering for the system that relied on data from a single angle of attack sensor. Through it all, Boeing had assumed that pilots would recognize a malfunction and react in four seconds. On March 30, a few hours after program leadership approved the expansion of MCAS, Forkner, according to Congressional investigators, sent a note to the FAA asking for MCAS to be removed from the aircraft’s Flight Crew Operations Manual. That left the Flight Standardization Board, responsible for determining the 737 Max’s minimum training, unable to evaluate its functional differences from the 737 NG.

That message from Forkner was the basis for the DOJ’s criminal prosecution of Boeing.

Was MCAS necessary at all?

Yet one haunting question still hangs over this tragic saga.

In completing its evaluation of the 737 Max for returning to service in Europe, Patrick Ky, Executive Director of the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) settled a central question that had hung over the Max development. The inclusion of the larger Leap engines did not impact the overall stability of the 737 Max.

“We also pushed the aircraft to its limits during flight tests, assessed the behavior of the aircraft in failure scenarios, and could confirm that the aircraft is stable and has no tendency to pitch-up even without the MCAS,” said Ky.

Read: Transport Canada safety official urges removal of MCAS from 737 Max

In TAC’s interviews with pilots, engineers and U.S. officials, much of the engineering consideration around the Max’s handling centered on the observed data during flight testing, rather than pilot impressions of actual differences in aircraft handling compared to the 737 NG.

FAA Administrator Steve Dickson at a February 2020 media briefing that the regulator had “gone back and looked at the airplane with the stall characteristics with and without the current MCAS system. And the stall characteristics are acceptable in either case.“

Those who have flown the Max in engineering tests tell TAC that much of the differences in handling qualities with MCAS present and not are marginally perceptible “once you know what to look for” and produces a “slightly softer feel” in the aircraft’s control for stall recovery.

Dickson had flown the Boeing 757 and 767 for Delta Air Lines, two airplanes that were designed together under a common pilot type rating. One is known by pilots as an overpowered hot rod, the other as a whale. While connected under the same rating for pilots, the two airplanes — one a single-aisle and the other a small twin-aisle — have different stall characteristics.

The Air Current asked Dickson on the sidelines of the Singapore Air Show in February 2020 that if the agency was on board with two different aircraft handling styles under the same pilot rating — as for 767 and 757 — why didn’t Boeing seek a waiver from the FAA 2 for pilots flying the 737 NG and 737 Max — two aircraft with slightly different handling?

“I don’t think we’ll ever know,” said Dickson. “The applicant brings forward a proposal, we evaluate the proposal. I’ve asked the same question myself.”

Write to Jon Ostrower at jon@theaircurrent.com

Following publication, an FAA spokesman on January 11 provided the additional statement regarding Administrator Dickson’s comments around Boeing’s selected path for meeting Federal Aviation Regulations for the original implementation of MCAS on the 737 Max. The Air Current sought and received comment from the FAA in advance of publication and that is reflected in the story above. We provide the latest response in full:

Any questions the Administrator raised about MCAS were in the nature of understanding the genesis of its addition to the flight control system and not a judgment on whether it was needed. That call has been, and always will be, left to the flight test pilots and engineers who are trained and qualified to make such determinations.

The fact of the matter is that the FAA — and the other authorities — determined during a 20-month review that MCAS was a necessary part of the flight control system. We all reviewed and approved the changes to the system as part of the recent certification.

This is directly addressed in the 100-plus page report that was filed with the Airworthiness Directive. We made it clear that the aircraft would not have been compliant with the stick force and G requirements and higher angle-of-attack without MCAS or some other type of mechanism. The FAA does not tell applicants how to design planes, so the choice to develop MCAS was an engineering decision on the part of Boeing. The FAA’s role is to evaluate and approve proposed designs against the regulatory requirements.

Subscribe to TACSubscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention