This post is also available in:

![]() 简体中文 (Chinese (Simplified))

简体中文 (Chinese (Simplified))

The 737 Max was born in the Admirals Club Lounge at Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport. On July 20, 2011, American Airlines was announcing it was buying 460 Airbus and Boeing aircraft to renew its fleet. One hundred were for a yet-to-be launched and yet-to-be named version of the 737 with new engines. American had purchased Boeing jets nearly exclusively for decades and Airbus had worked on American unceasingly to break Boeing’s hold at what would eventually become the world’s largest airline. It pulled out all the stops. Just 10 days before, top Airbus executives waited to meet American’s then-CFO Tom Horton in the sweltering heat at the finish line of the Texas Too Hot 15K footrace to make the final hard sell. It worked.

The deal had set off a chain of events that led to today — a global safety crisis facing Boeing’s most important airplane.

Boeing wanted to replace the 737. The plan had even earned the endorsement of its now-retired chief executive. “We’re gonna do a new airplane,” Jim McNerney said in February of that same year. “We’re not done evaluating this whole situation yet, but our current bias is to not re-engine, is to move to an all-new airplane at the end of the decade.” History went in a different direction. Airbus, riding its same decades-long incremental strategy and chipping away at Boeing’s market supremacy, had made no secret of its plans to put new engines on the A320. But its own re-engined jet somehow managed to take Boeing by surprise. Airbus and American forced Boeing’s hand. It had to put new engines on the 737 to stay even with its rival.

Subscribe to TACBoeing justified the decision thusly: There were huge and excruciatingly painful near-term obstacles on its way to a new single-aisle airplane. In the summer of 2011, the 787 Dreamliner wasn’t yet done after billions invested and years of delays. More than 800 airplanes later here in 2019, each 787 costs less to build than sell, but it’s still running a $23 billion production cost deficit. A new single-aisle jet risked unlocking all its stalwart operators who banked on the continuity between 737 generations.

Related: China’s aviation regulator orders grounding of 737 Max

An all-new jet meant leaving the past behind, along with its established infrastructure. With a lower-cost alternative in the A320neo not hamstrung by having to pay for a fresh $15 billion development, a new Boeing jet risked giving Airbus dominant market share. In the wake of a record oil run-up in 2008, airlines wanted fuel efficiency at a current-technology price.

The 737 Max was Boeing’s ticket to holding the line on its position – both market and financial – in the near term. Abandoning the 737 would’ve meant walking away from its golden goose that helped finance the astronomical costs of the 787 and the development of the 777X.

The 737 Max is a product of that environment where short-term decision-making can drive big and often painful pushes for product improvement. It’s one that I’ve written about extensively over the years, and born from the work of academics like Dr. Theodore Piepenbrock and his work on the Evolution of Business Ecosystems.

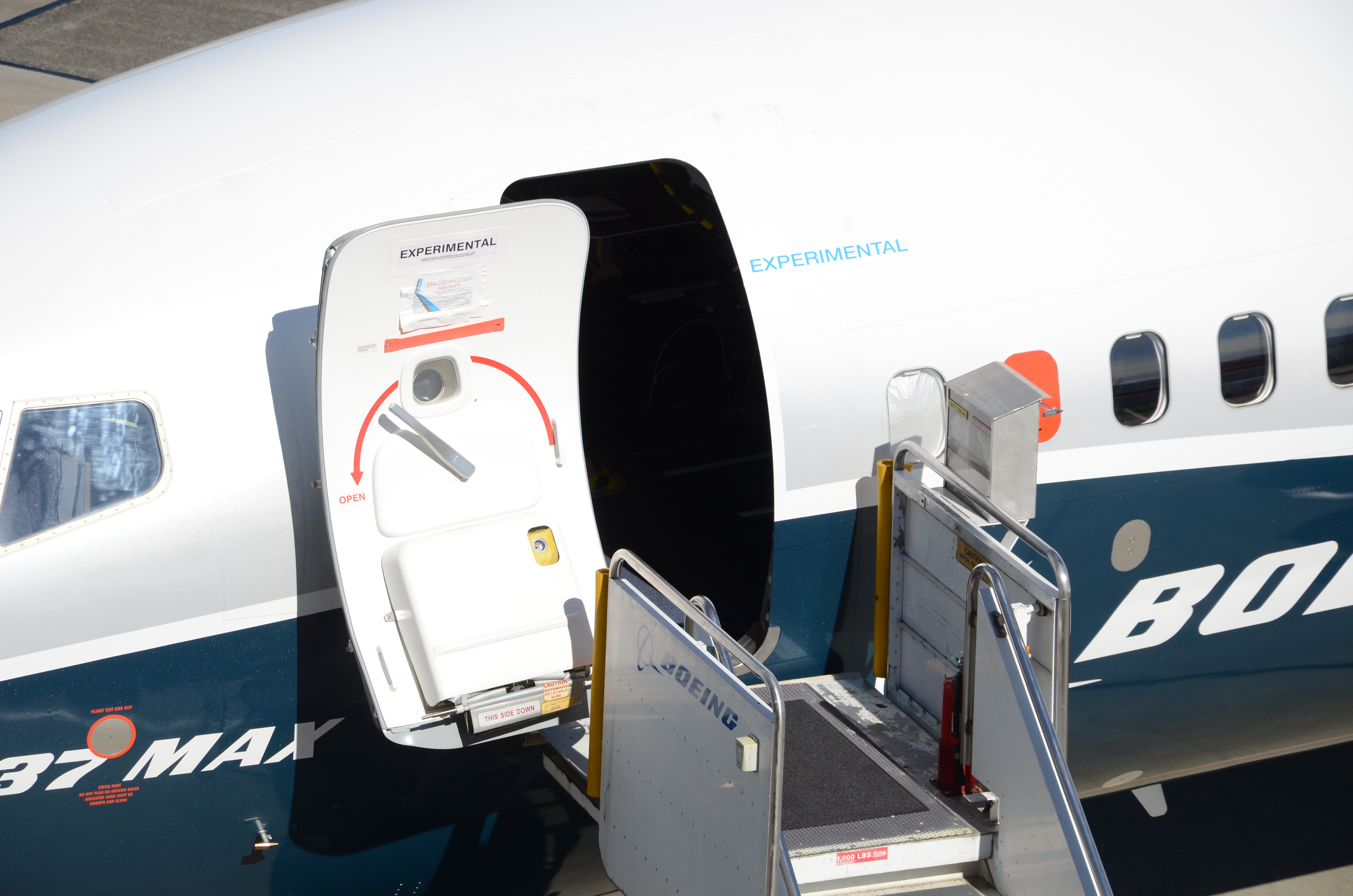

Every airplane development is a series of compromises, but to deliver the 737 Max with its promised fuel efficiency, Boeing had to fit 12 gallons into a 10 gallon jug. Its bigger engines made for creative solutions as it found a way to mount the larger CFM International turbines under the notoriously low-slung jetliner. It lengthened the nose landing gear by eight inches, cleaned up the aerodynamics of the tail cone, added new winglets, fly-by-wire spoilers and big displays for the next generation of pilots. It pushed technology, as it had done time and time again with ever-increasing costs, to deliver a product that made its jets more-efficient and less-costly to fly.

In the case of the 737 Max, with its nose pointed high in the air, the larger engines – generating their own lift – nudged it even higher. The risk Boeing found through analysis and later flight testing was that under certain high-speed conditions both in wind-up turns and wings-level flight, that upward nudge created a greater risk of stalling. Its solution was MCAS, the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System control law that would allow for both generations of 737 to behave the same way. MCAS would automatically trim the horizontal stabilizer to bring the nose down, activated with Angle of Attack data. It’s now at the center of the Lion Air investigation and stalking the periphery of the Ethiopian crash.

Related: What is the Boeing 737 Max Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System?

The point, made awkwardly by the President of the United States Tuesday morning on Twitter without naming Boeing directly, was that the complexity of aviation technology was being pushed too hard and at too great a cost to safety, all in the name of economics.

“Split second decisions are needed, and then complexity creates danger,” Trump wrote. “All of this for great cost yet very little gain.”

Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg reportedly spoke with President Trump earlier Tuesday, urging him not to ground the jet.

Lion Air 610 should never have been allowed to get airborne on October 29, a conclusion shared by those familiar with the inquiry. The plane simply wasn’t airworthy. According to the preliminary investigation, PK-LQP’s Angle of Attack sensors were disagreeing by 20-degrees as the aircraft taxied for takeoff. A warning light that would’ve alerted the crew to the disagreement wasn’t part of the added-cost optional package of equipment on Lion Air’s 737 Max aircraft. A guardrail wasn’t in place. Once the aircraft was airborne, the erroneous Angle of Attack data collided with an apparently unprepared crew with tragic consequences as the MCAS system repeatedly activated, driving the jet’s nose into a fatal dive.

We do not yet know what befell Ethiopian Airlines flight 302. The broad circumstances are similar to those in Indonesia. An apparent loss of control shortly after takeoff on a brand new airplane. The isolated event data, the information that lives on the damaged flight data recorder, may establish or disprove a direct technical link between the two crashes. But the macro-data – the broader context – is an airplane whose design has been repeatedly pushed and pulled under cost pressures and grandfathered certification requirements over decades, finds itself in the middle of two catastrophic aberrations in an era of unprecedented aviation safety.

Related: Southwest is adding new angle of attack indicators to its 737 Max fleet

If it was Southwest Airlines and American Airlines and not Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines five months apart, the 737 Max fleet would’ve been grounded by Sunday evening, according to senior U.S. industry officials and aviation safety experts. In an aviation universe that requires stakeholders to be aligned, the events of the last 48 hours are a stark divergence. From China to Europe, regulators and airlines have said it was time to stand down the 737 Max fleet “as a precautionary measure,” according to European Aviation Safety Agency.

Boeing in a statement Tuesday said, “We understand that regulatory agencies and customers have made decisions that they believe are most appropriate for their home markets. We’ll continue to engage with them to ensure they have the information needed to have confidence in operating their fleets.”

The Federal Aviation Administration said Tuesday in a statement that “our review shows no systemic performance issues and provides no basis to order grounding of the aircraft. Nor have other civil aviation authorities provided data to us that would warrant action…If any issues affecting the continued airworthiness of the aircraft are identified, the FAA will take immediate and appropriate action.”

The 737 assembly line in Renton, Wash. is a marvel of lean manufacturing. The line inches forward little-by-little as assembly proceeds. Born from Toyota’s production methods, the process is one of continual improvement. It’s what made the 737 the lifeblood of Boeing in the first place and why this crisis, taken to its most extreme, could threaten the company’s very existence. But the assembly line also comes with a tool called an Andon cord. The cord empowers all employees to pull it and stop the line if something is amiss or requires investigation and needs fixing. The rest of the world has already pulled it.

Subscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention