Log-in here if you’re already a subscriber

A week after the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, Boeing laid off 30,000 people. On top of the incalculable human tragedy, the event was a tremendous shock to the U.S. and global economy. Confidence in the safety of the skies had been shaken to its very core. The company would have to “resize” its business for this new reality where fewer wanted to fly.

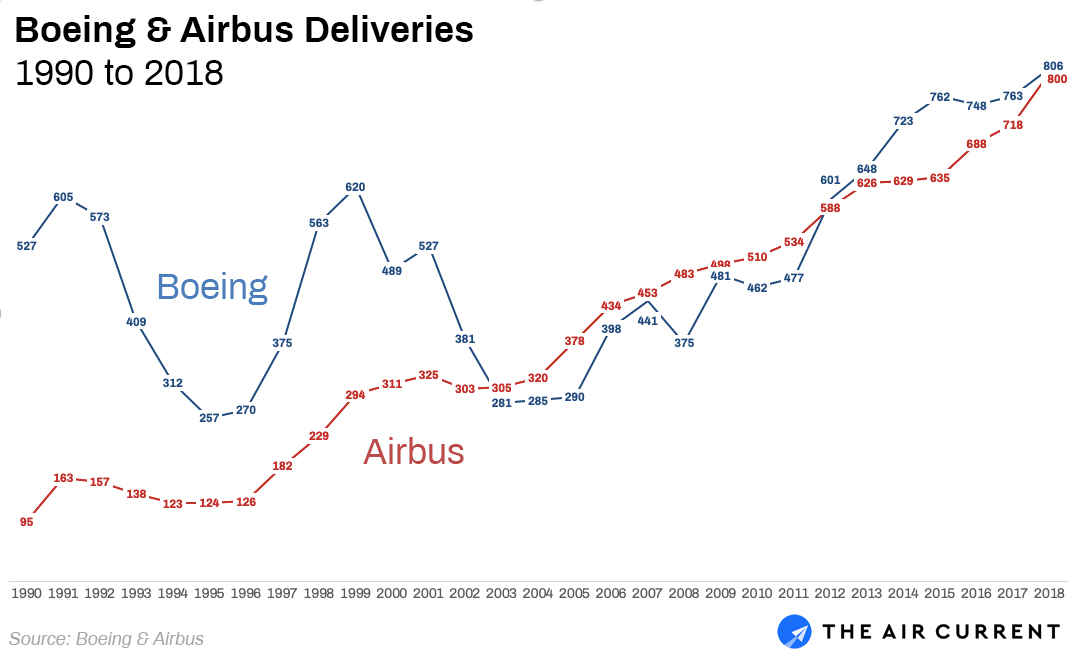

Years later as economists made sense of the data, it became clear that 9/11 was an accelerant, not the trigger, for the economic contraction. The U.S. economy had begun to contract six months earlier as the dot.com bubble burst. During the exuberance, production at Airbus and Boeing – primarily Boeing – had stuffed too many airplanes into a market that, before the attacks, had already been straining.

It was the last time Boeing was introducing a major new update to the 737 (the Next Generation 737) sprinting at record production as it worried about market share losses at the hands of Airbus. Both cut output. As the recession deepened after 9/11, deliveries at Airbus fell about 6% from its 2001 peak. From Boeing’s own 1999 peak to bottoming out in 2003, output plummeted 55%. Boeing had boomed, racing to maintain its position, and then it busted.

It was a turning point. Once a small European upstart, Airbus was dismissed as a make-work aerospace jobs program by those inside its U.S. rival. It had now taken the lead. Boeing had an equal in Airbus and they’ve been running neck and neck ever since.

Boeing and Airbus have enjoyed the largest sustained peace-time production expansion in history. The pair developed three all-new airplanes and made major updates to the A320 and 737 as the world’s airlines pined for low-cost growth. But after 15 years of boom (even through the financial crisis), cracks are showing in the supercycle.

But the inherent industry cyclicality is no bug, rather a feature, of those supplying the market, posits Dr. Theodore Piepenbrock, who is director of the International Institute of Strategic Leadership. His academic work at Oxford and MIT points directly to the manufacturers as the cause of the industry’s cycles. External factors like 9/11, SARS or the financial crisis always occur, but short-term incentives create unsustainable hard swings in everything from product design to supplier and labor relations and ultimately production. This is a hallmark of Boeing strategy, he concludes, making such ups and down predictable, including the latest in 2019.

Related: The world pulls the Andon Cord on the 737 Max

A swirl of factors surround the future for Boeing and the 737 Max: A crisis of confidence after the crashes of Lion Air 610 and Ethiopian Airlines 302, an uncertain resolution to the jet’s grounding and a market bulging with airplanes. Now supplier, leasing and airline executives from around the world are expressing concern that the grounding of the 737 Max is the ‘black swan’ event — the exogenous shock — that will accelerate a cyclical downturn that was already here, as airlines who bought too many planes take cover under its wing.

Subscribe to TACSaudi low-cost startup Flyadeal, which ordered up to 50 737 Max aircraft in December was quick throw its order in question immediately after the grounding. Air travel demand in the Middle East didn’t grow in 2018, chopping 3.1% out of the region’s load factor. Long-struggling Malaysia Airlines said it was reviewing its order for 25, Garuda Indonesia’s 50, too. Lion Air, already struggling before the October crash of flight 610, said it was moving forward with abandoning its Boeing order, still the largest single purchase in the plane maker’s history. SpiceJet and Norwegian both said it would seek compensation from Boeing for the grounding. And Air Canada and WestJet have both suspended financial guidance. WestJet said it could cover 75% of its Max flights with other aircraft.

A downturn upon us

But beyond the groundings, the bigger industry question looms. “I think this is the beginning of a downturn,” said Peter Chang, Chief Executive of the aviation arm of the Hong Kong-based China Development Bank. (CDB itself has ordered 168 737 Max and A320neo aircraft) His comments from March 12 came in an unlikely venue: A gathering of the aviation financial and operational community last week in Orlando, Fla.

The high oil prices that brought us the more fuel-efficient 737 Max and A320neo also came with a the subsequent collapse in the price of jet fuel and plentiful cheap capital. Low cost carriers saw a chance to grow and legacy airlines saw a way to keep pace and block their ascent.

Since the beginning of 2013, airlines of all stripes have taken delivery of around 6,200 A320s and 737s, representing the largest fleet expansion in aviation history. Retirements of elderly MD-80s, 737 Classics and the oldest A320s and Next Generation 737s accelerated during that period, but according to Cirium annual fleet census data from mid-2013 to mid-2018, the Airbus A320 and Boeing 737 fleet grew sharply from 10,600 to 14,800 aircraft in service, an increase of nearly 40%.

Related: Echoes of 1997 production meltdown in 737 pileup

The pace of purchasing of next generation aircraft has been mind-boggling. 5,012 737 Max aircraft 6,501 A320neo have been ordered since 2010. Airlines have been buying to double, or even triple or quadruple, their size of just a few years ago. Indigo bought 430, Lion Air 464, 200 for Norwegian, 250 for Flydubai. In the U.S. for example, Frontier Airlines would aim to triple its fleet. A carrier like Copa Airlines looks modest by comparison, adding only 61 737 Max jets to its fleet of about 100, some of which will be retired.

The collapse in fuel in 2015 and 2016 caused fares to fall 16% and accompanied “an acceleration in the number of city-pair connections, which boosts demand, facilitated by increasing deliveries of longer-range narrow body aircraft,” according to a February report from the International Air Transport Association.

“The low price of oil raises the ever-increasing threat of overcapacity,” wrote Embraer Commercial Aviation President John Slattery in February. “How? The lower price of oil tempts airlines into backsliding on their strategy of disciplined growth. It reduces the pressure to cut costs and capacity.”

In 2018, signs of oversupply are increasing. According to IATA global capacity of available seats grew at 6.1% in December — demand trailed at 5.3% as load factors and yields fell. In the domestic markets in the U.S, China and India, packed with new 737 Max and A320neo aircraft, where capacity is growing “much faster than demand,” according to Slattery.

The data was clear: “Profits are declining, revenue momentum is slowing, and unit costs are on the rise”, Slattery wrote. “Profits will be higher than the cost of capital, but in our cyclical business, the peak of this particular cycle is definitely behind us. The global airline industry has left the expansion phase and is now in the descent phase,” wrote Slattery, who advocates for airlines to buy smaller airplanes like the Embraer E2.

“There’s nothing new about the correlation between cyclical demand, over capacity, dropping load factors and eroding yields in the descent phase. Yet carriers repeatedly maximize short-term gain at the expense of long-term pain,” wrote Slattery. The same is true for aircraft manufacturers, happy to oblige the excess.

Related: China’s aviation regulator orders grounding of 737 Max

Upon grounding its 737 Max fleet last week, Chinese airlines reported little pressure or disruption from taking nearly 100 aircraft out of its air transport system. Globally, about 4% of the brand new Max fleet of 387 aircraft (15 are sitting in storage) haven’t flown in weeks, according to Flightradar24. About half of those are for struggling Jet Airways – the balance for LOT Polish, China Southern, Travel Service, Icelandair, Air Italy, Norwegian and FlyDubai.

Even as deliveries have been paused by the grounding, Boeing production of 737 Max aircraft continues unabated.

Across the industry, the ups and down of trade wars, actual wars, the economic uncertainty brought by Brexit, and broader travel restrictions are taking their toll on the industrial chain.

“I am getting really queasy on the macroeconomics impacting global carriers,” a top executive at a major supplier to Boeing, Airbus and the airlines tells The Air Current and it’s getting more challenging to get paid on time. “We are having to hammer on receivables from airlines that never used to have issues before.”

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated said that capacity growth in 2018 outstripped demand, according to the International Air Transport Association. A year-over-year comparison of December 2018 data identified capacity growing faster than demand.

Subscribe to TACSubscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention