- The magnitude of the COVID-19 impact on air travel now compares with the September 11, 2011 terrorist attacks on the United States.

- 9/11 was an inflection point for U.S. premium business air travel and has never recovered.

- The current crisis could reset premium travel globally, accelerating existing trends and leaving a permanent mark on the industry.

Not since the terror attacks of September 11, 2001 has air travel so swiftly plummeted. As The Air Current takes stock of the global impact of COVID-19, the 2001 attacks not only offer an historical parallel to the sharp drops in air traffic, but an insight into what may come next when people return to flying.

COVID-19 has gone global and the World Health Organization has warned that the spread of the virus is reaching pandemic conditions. With that amplified spread across Asia, Europe and increasingly North America, the disruption to air travel networks is following close behind.

Related: Once scarce, coronavirus creates a glut of unneeded airliners

Initial comparisons to prior regional crises such as SARS, MERS, and Ebola, including own earlier analysis, are no longer sufficient as global demand continues to drop.

Subscribe to TACAlready, we are seeing evidence of wide-scale reduction in discretionary business travel, as companies reassess all non-essential travel along with widespread cancellation of large events and conferences. Not since 2001, has the airline industry witnessed such a sharp reduction in travel demand. If only for historical perspective, the comparisons are undeniable. With clear signs of forward bookings down between 50-80% in some regions, the economic damage inflicted by the global response to coronavirus increasingly looks like the industry’s next 9/11. On Tuesday, United Airlines President Scott Kirby said bookings (excluding cancellations) to Asia are down 70%, 50% across the Atlantic and 25% domestically.

It is within this context that The Air Current can begin to look at the possible long-term effects of the current crisis. How did traffic recover after 9/11 and what can that recovery tell us about the future for airlines on the other side of COVID-19?

The economics of post-9/11 flying

By all accounts, traffic recovered after 9/11. Domestic traffic had fully recovered by 2004, on the front end of the wave of bankruptcies and consolidation that would define the decade.

Yet, as we look closer, the fall-out from the recession and the 2001 attacks represented a fundamental shift in the market. In 2001, the business travel industry was faced with a crisis of how to continue doing business without the ability to fly. This necessity led to a wholesale change in how domestic business travel was conducted. Whether it be from fear of traveling, lack of funds, or new technology enabling business interaction without the need to travel, the industry’s premium passenger never recovered.

Related: A jittery industry begins to question if business travel will rebound after coronavirus

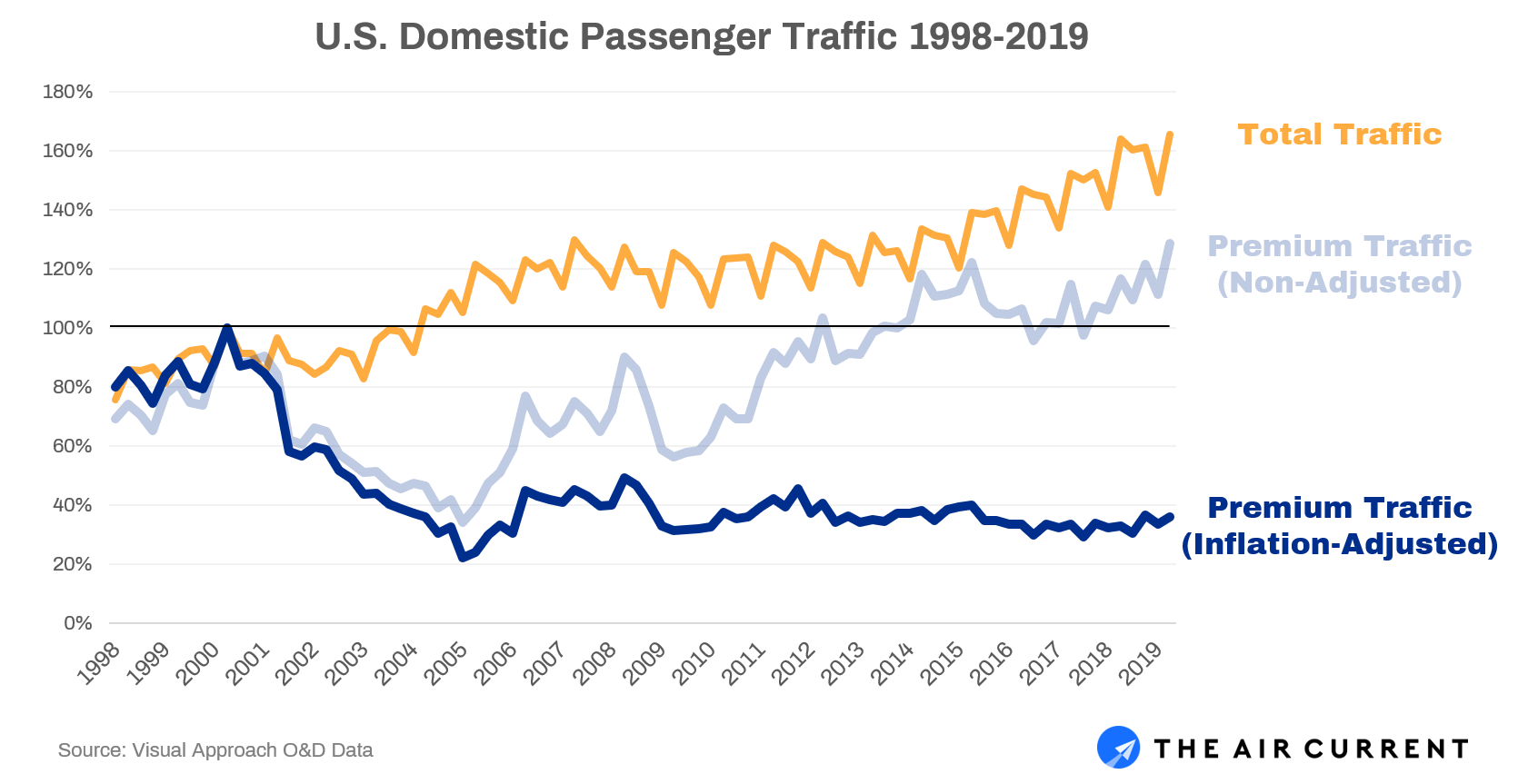

Looking closer, as the world watched overall traffic return to set new record levels by 2004, the number of people willing to pay the high ticket prices on which the industry came to rely did not return. It wasn’t until 2012 before there were again approximately 40,000 daily passengers willing to pay more than $500 for a domestic ticket as did in 2000, according to our analysis1. Crucially, when adjusted for inflation, not only did this high-yield, premium traffic never return, it still remains at only 40% of what it was in 2000. This 60% decline in domestic high-yield traffic occurred in parallel with an overall industry that grew 60%.

The industry has never fully recovered from 9/11 – it realized and eventually adapted to a new reality, along with the shifting competitive dynamics. This new reality included more traffic, lower fares, and new low cost carriers, enough to warrant a designator of their own, creating the “Ultra Low Cost Carrier”. All this was the hallmark of a maturing industry’s quest for ever-lower unit costs. It also included the new reality of business travel taking place behind the first class curtain, an extra-legroom economy seat, the rise of fractional jet ownership providing a high-end alternative, and a generation increasingly comfortable interacting through ever-more capable technology.

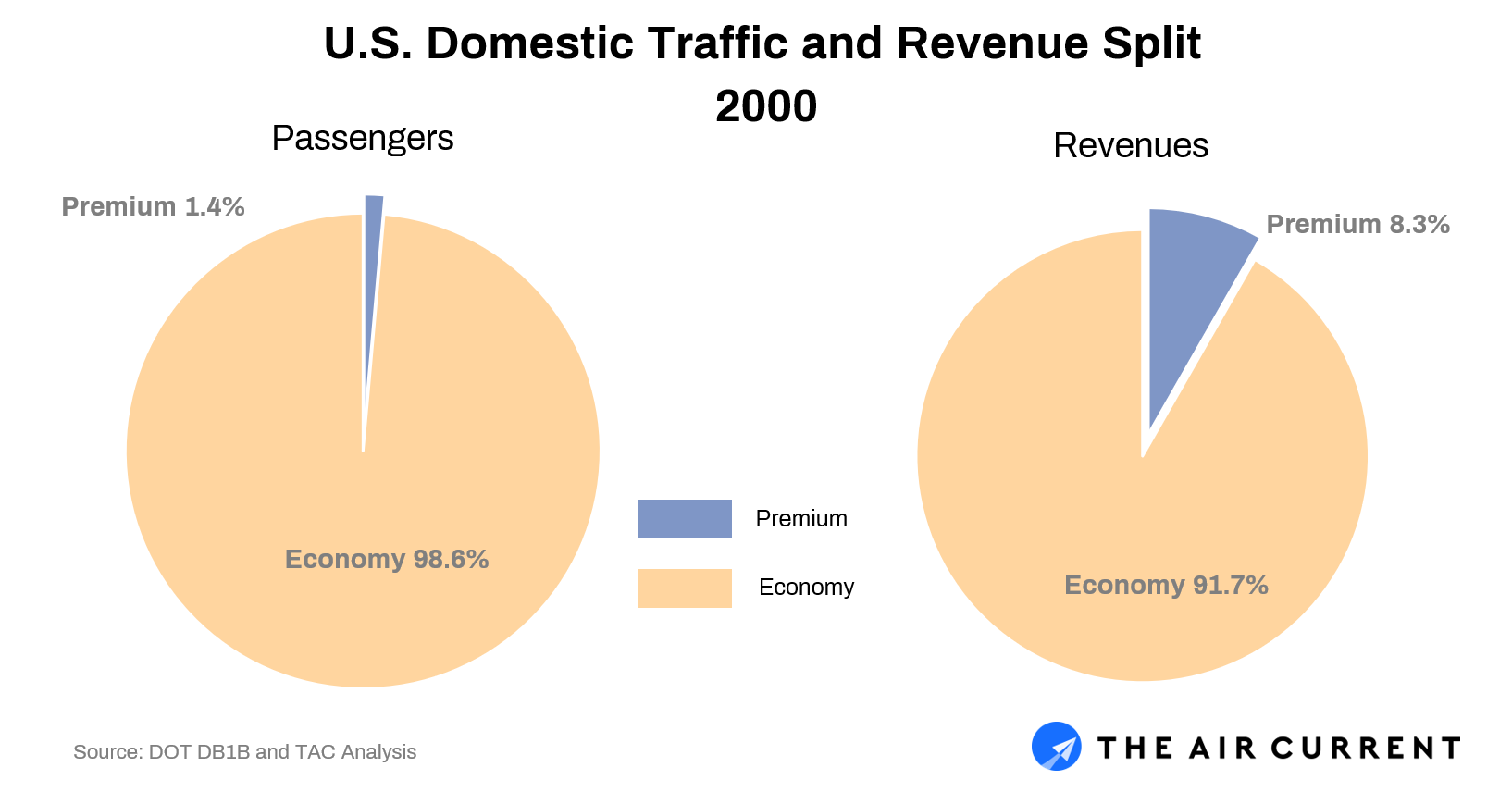

Once accounting for just 1.4% of the domestic passengers flown, these premium customers represented over 8% of the passenger revenues at the peak in 2000, according to the DOT’s DB1B dataset, cleaned and adjusted for taxes. Since then, domestic first class flying has shifted to more of an upgrade model, with fewer people paying for the higher tickets and instead a perk for loyal customers for the right to sit in seats that used to cost more than $1,000 per round trip.

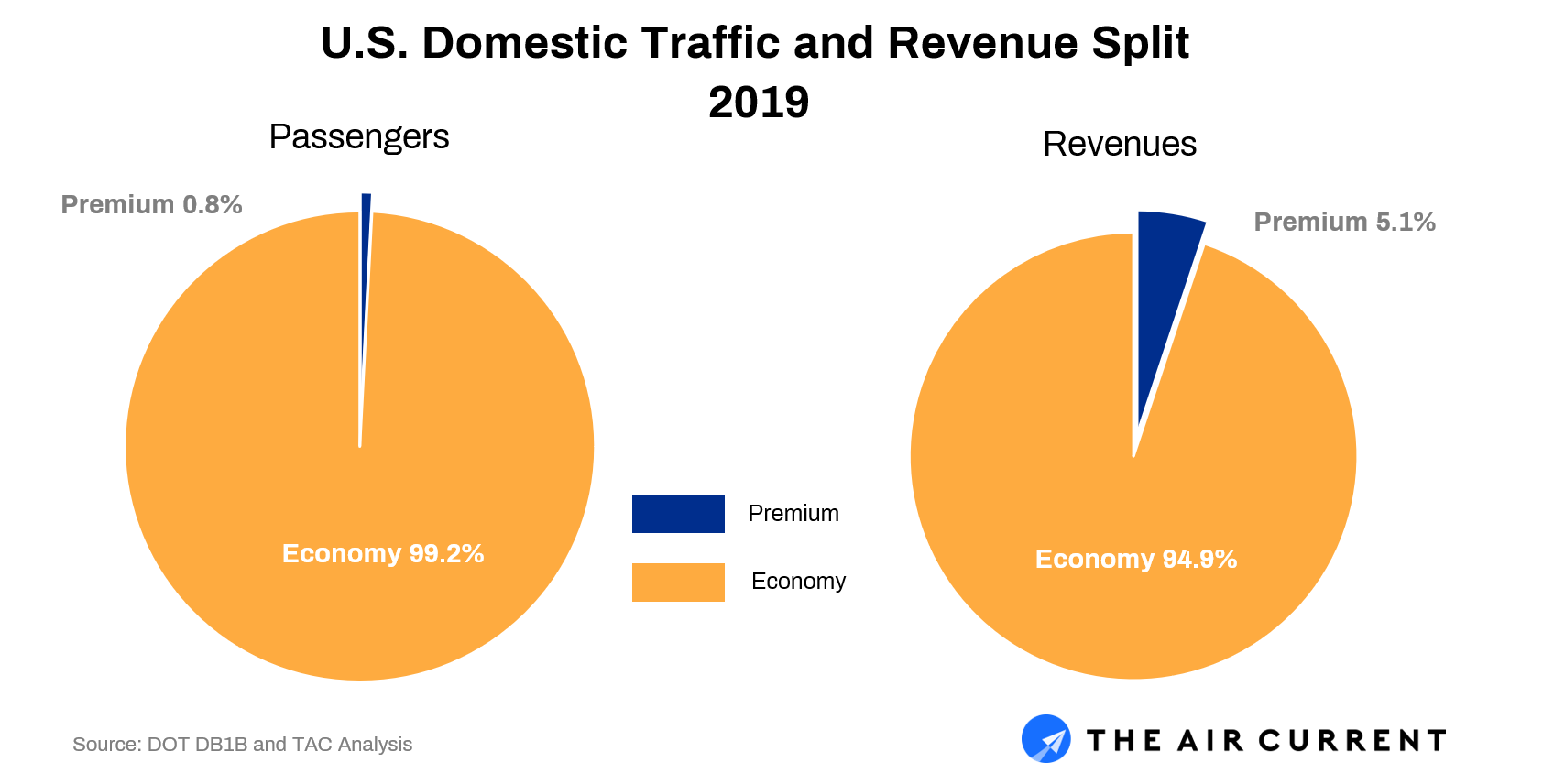

Today, the number of passengers willing to pay the 2001 equivalent of $500 ($728 in 2019 dollars) has dropped to lower than a percent, representing only 5% of the total passenger U.S. ticket revenue. When considering the addition of checked bag fees, seat selection charges, and higher change fees that have evolved over the past two decades, this impact of premium revenues is further diluted as increasingly, revenues are now generated on an ancillary basis.

For an industry that relied heavily on premium revenues in 2000 which evaporated in September the following year, the inevitability of the bankruptcies of the 2000’s becomes clear. Airlines which came to become dependent on these domestic premiums were forced to compete with the low cost carriers, for whom traffic had returned relatively quickly, scooping up price-sensitive flyers.

Related: Coronavirus is seizing the engine of global commercial aviation

Fast forward almost 20 years to the next great disruption in global air travel. Once again, companies are faced with the inability to travel, if not from reduced demand and volatility, then from the liability implications of an employee who may contract the new virus while traveling on company business. Much as we saw in 2001 (and not since), companies are forced to find alternative ways to conduct business without travel.

Yet unlike in 2001, the domestic market has already long-absorbed the new reality of lower premium traffic. Given that shift, it is the ultra-high-yield international markets that remain vulnerable to a similar reduction in premium traffic and historically bountiful fares.

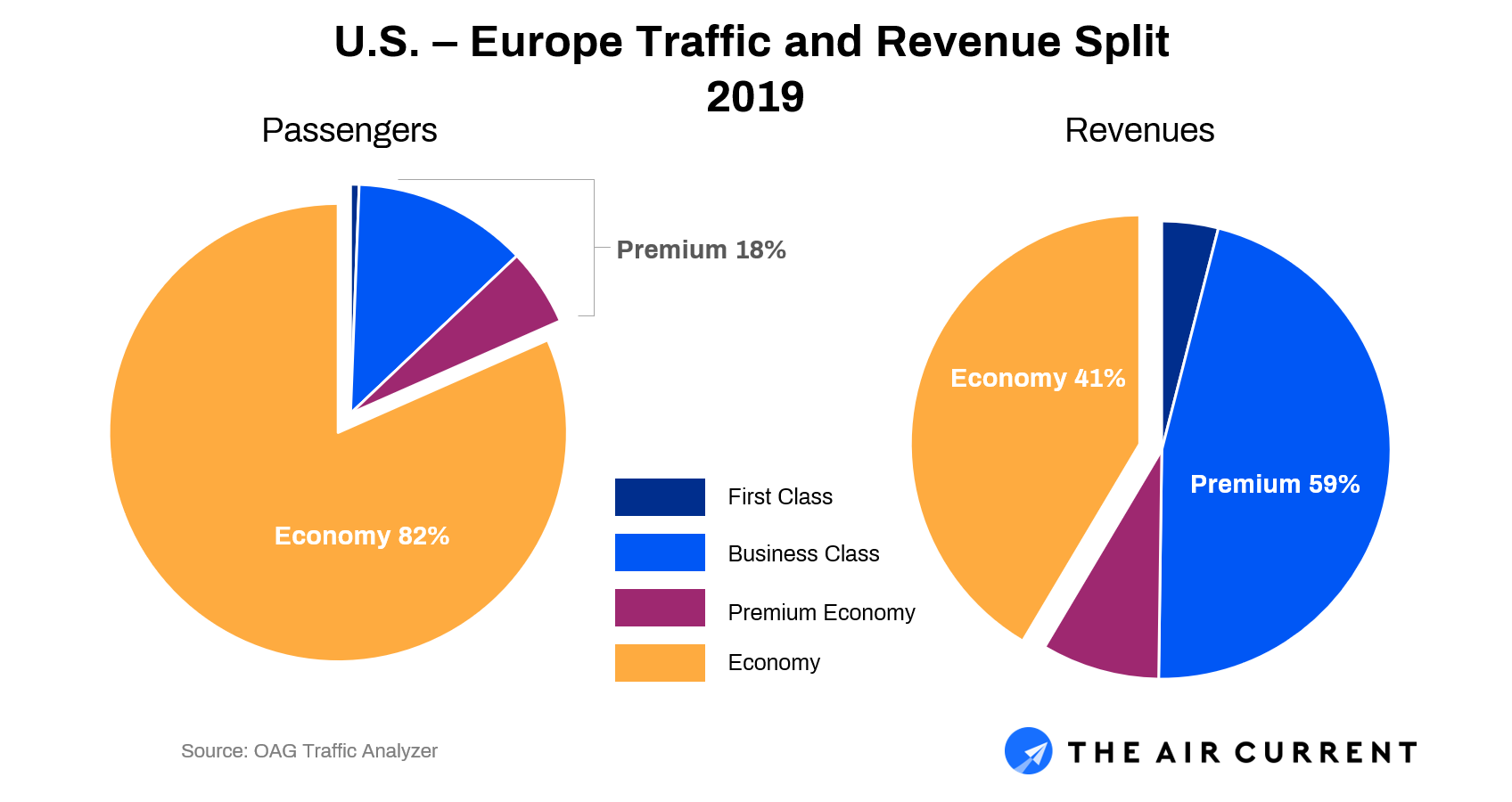

In stark contrast to the evolution of the post-9/11 U.S. domestic market that already adapted to the evaporation in premium passengers, the long-haul international market has come to utterly depend on these same premium fares. While 82% of wide-body aircraft are filled with economy passengers and sprinkled with a handful of premium seats, the airlines realize a disproportionate premium market sprinkled with a handful of economy passengers. Over 59% of transatlantic ticket revenues are paid through premium seats; seats which are largely occupied by the very businesses that are now cutting discretionary travel.

At this early point in the crisis, the question remains whether this long-haul premium passenger will return in the same way. In short, we do not know. Yet, considering the other segments (domestic economy and premium, and international economy), the international premium remains the most vulnerable to a prolonged recovery. As companies learn to survive and excel with the available alternatives today, the pressure to place large teams in expensive premium seats may shift, just as it did in the U.S. domestic market following 2001.

To be sure, low-cost carriers had advanced the trend away from premium air travel, but 9/11 was a definitive turning point for that acceleration when coupled with a precipitous downturn and drop in demand.

Further implications of a sustained reduction in premium long-haul travel could disproportionately affect the wide-body aircraft market, as well. Already described as “apocalyptic” during the International Society of Transport Aircraft Trading (ISTAT) America’s symposium last week, the wide-body market could sustain further devaluation, migrating pressure beyond the airlines to lessors, aircraft manufacturers, and ultimately the larger supplier community.

Related: Visual Approach: Can the A321XLR Replace Wide-Body Aircraft Across the Atlantic?

The hit also comes at a time when new narrow-body aircraft such as the A321XLR will begin to open the low cost airlines to international markets currently dominated by these premium fares. JetBlue Airways, for example, explicitly said its goal was to reset what it viewed as exorbitant fares on the North Atlantic from Boston and New York. While long-haul wide-body low cost operations have not had a successful track record, the current setup is conspicuously similar to that seen in the U.S. domestic market in 2001. This international situation is one which LCCs employing the new smaller, longer-ranged aircraft could begin to take advantage.

This risk to future long-haul yields brings various levels of exposure to the airlines. If the industry does, in fact, see a drop in premium travel to the likes seen in 2001, long-haul airlines would be most impacted, particularly European and Middle Eastern carriers with large fleets of wide-body aircraft and few passengers left to fly on them — or at least at the prices they are used to charging. That dynamic could also largely protect a U.S. industry, with comparatively lower exposure to long-haul flying and much more dependence on domestic travel; domestic travel which has already gone through drastic changes from a crisis almost twenty years prior.

Traffic is expected to return once the COVID-19 effects have passed, just as we saw following the 2001 attacks. Yet, history shows it is the makeup of this traffic that could leave a lasting mark on the industry beyond the initial shock.

Write to Courtney Miller at courtney@theaircurrent.com

Subscribe to TACSubscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention