The Air Current welcomes Courtney Miller as its new Managing Director of Analysis.

- Air travel is inherently a vector for coronavirus to spread, but so far has also been instrumental in stopping a global metastasis.

- With current cancellations through March, U.S. airlines’ halt in flying to China cost approximately $110 million.

- Regardless of the outcome of the 2019-nCoV outbreak, the market will recover.

- We expect market recovery within 12 months of resumption of flights, however challenges still exist beyond the outbreak.

On March 12, 2003, the World Health Organization issued a global travel alert for a mysterious form of pneumonia spreading in China and Southeast Asia. Within a month, travel to the region began to plummet as fears grew on the spread of the new virus, and travel advisories were increased to include all of mainland China. The recovery from SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, also a coronavirus) was almost as quick as the panic subsided, and the outbreak was declared contained by July of that year.

Seventeen years later, China faces yet another coronavirus; one that is much less deadly yet much more easily transmitted, according to global public health officials. The fate of this new virus is largely irrelevant. Whether this latest coronavirus is contained as quickly as SARS or becomes a world-wide seasonal illness (a global pandemic) is yet to be seen. In either scenario, we believe the panic will inevitably subside and traffic will recover.

In the intervening two decades, China’s role as an engine of global air travel growth has made the nation the second largest air travel market on Earth. It is expected to overtake the U.S. as the number one air travel market by 2025, according to a report by the International Air Transport Association.

Subscribe to TACAir travel inherently provides a vector for the disease, but so far has also been instrumental in stopping the global spread of coronavirus. As of February 9, more than 37,500 people had been confirmed to have been infected with the coronavirus, 99.2% of those inside China, according to the WHO. This leaves less than 1% of the infected outside of China, early evidence of the effectiveness of the proactive cancellations.

In this first TAC Analysis we look at the history of the U.S. / China market, and its unique recovery from a feared pandemic. It remains early in the fight against coronova virus. While we cannot forecast when the travel restrictions will be lifted, we can use SARS as a measure for how it could recover once the panic has subsided.

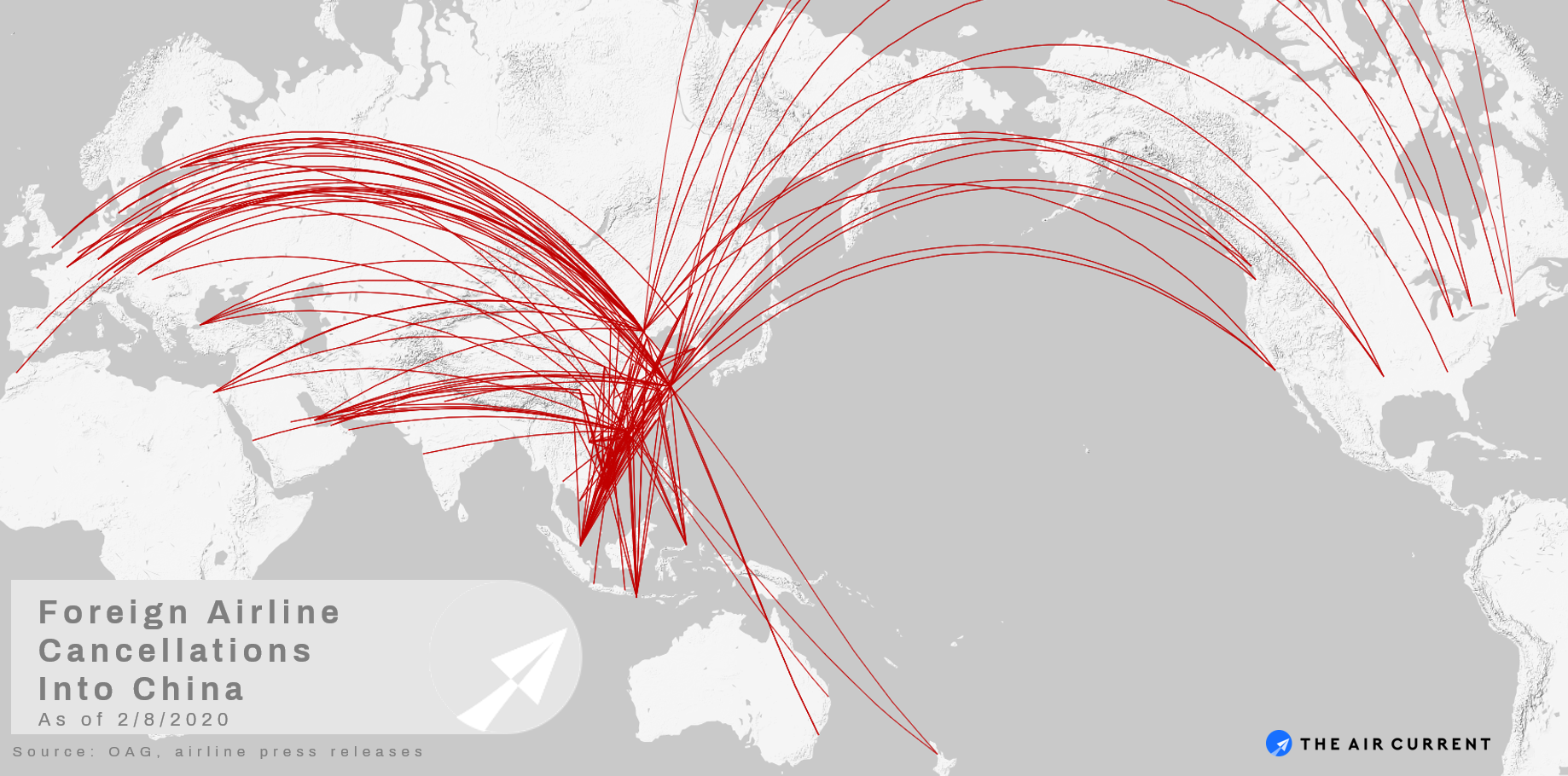

As of this map being compiled, over 300 cities had lost their connection to China and the continued uncertainty of more is further depressing demand. The situation remains fluid with additional announcements from Beijing Capital, Air China, and Cathay Pacific.

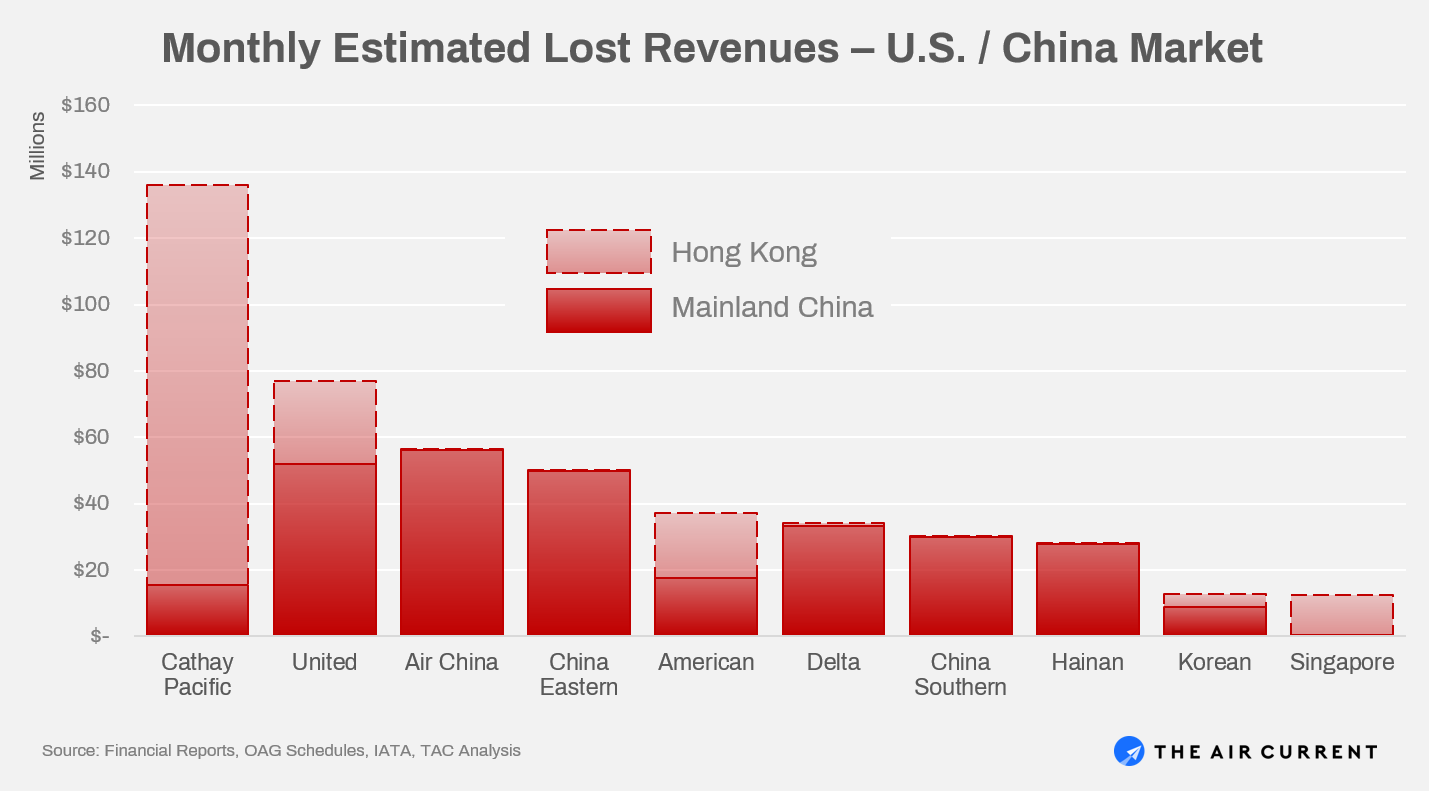

The constant change in cancellations increases the challenge of identifying the impacts to the industry. Focusing on the known mainland market alone, the impact to revenues from the currently planned two months of cancellations varies across not only Chinese and U.S. carriers, but also connecting carriers such as Korean Air and Singapore Airlines.

The financial hit to U.S. airlines

Chinese carriers have the most to lose in the U.S. market, which says nothing of the massive losses they will in other international markets, as well as domestically. Air China and China Eastern have the most exposure to mainland China traffic, while Cathay Pacific has extreme risk should the Hong Kong markets close.

Of the U.S. carriers, United Airlines operates the most service to mainland China through their hubs in San Francisco, Chicago, Los Angeles, Washington Dulles, and Newark, as well as Hong Kong service through San Francisco and Newark. Mainland China flights have been cancelled through March 28 for United, while the Hong Kong cancellations are currently scheduled to resume February 20.

Delta Air Lines is halting operations to mainland China through April 30. With service to China from Seattle, Detroit, and Atlanta, Delta does not currently fly to Hong Kong.

American Airlines has the fewest mainland flights, serving only Shanghai and Beijing from their Dallas and Los Angeles hubs. The cancellations for American will continue through March 27, however the airline’s presence in the Hong Kong market with their Cathay Pacific partner could double their exposure. Flights to Hong Kong are currently cancelled through February 21.

Further challenges will come for these network carriers as connecting flights into their international hubs no longer carry China-bound traffic. As a result, domestic fares on these markets are expected to take a hit as fewer seats are filled and revenue management systems respond.

China Eastern has halted all U.S. service, while Air China and China Southern have significantly reduced flights. Precisely how many passengers may be allowed to transit remains unclear due to entry restrictions by the U.S. government.

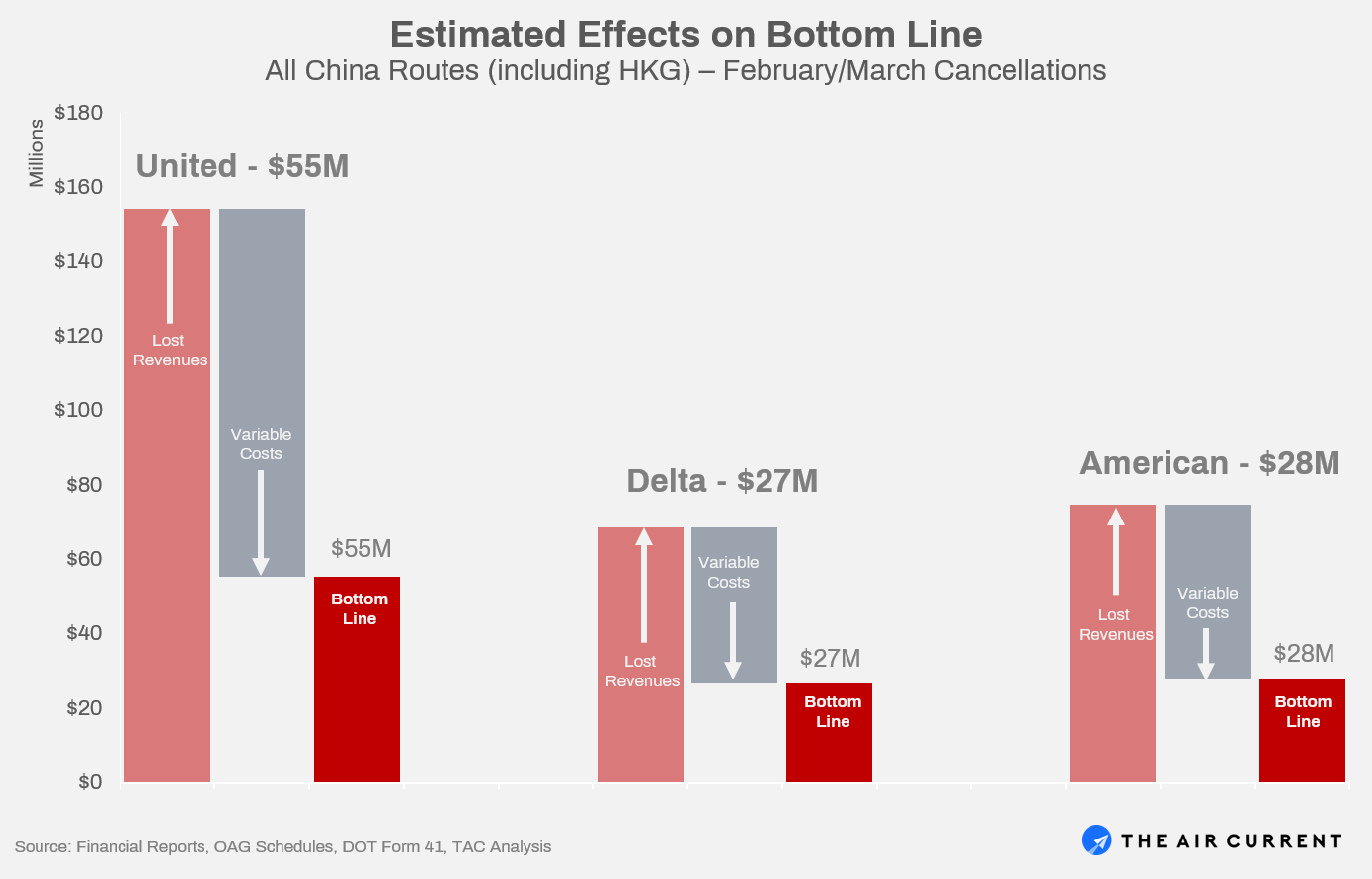

Not flying has economic benefits. The loss of revenue is at least partially offset by reduced variable costs. Cancelled flights mean no ticket revenues, but they also remove the requirement that the aircraft physically operate the flight. These reduced costs are largely limited to fuel, maintenance, catering, and landing/terminal fees, while expenses such as crew salaries and aircraft ownership continue to be paid. With the recent addition of Hong Kong to the list of cancelled service for the U.S. airlines, the impact to the bottom line will be felt.

Lost revenues of flying to China won’t, however, translate to equivalent hits to the bottom line. Should cancellations continue, even the fixed assets would be re-appropriated through different portions of the network, further decreasing the impact. While the loss of revenues is impactful, the inevitable return should not cost any airlines market share, assuming service is returned promptly.

Based on TAC Analysis estimates and the assumption the Hong Kong cancellations extend through March, United remains the most impacted with almost $160 million in lost revenues from all China service over the February and March cancellations versus the same months in 2019. This is largely offset by the reduction in variable costs, leaving United with an estimated $55 million impact to their bottom line over the two months.

Delta operates no Hong Kong service, yet is the second largest U.S. carrier in the mainland China market, while American is disproportionately exposed to Hong Kong with their local Oneworld partner, Cathay Pacific. Should the cancellations continue beyond March, the impact will grow as the market begins to enter what would have been its peak season.

A history of resiliency

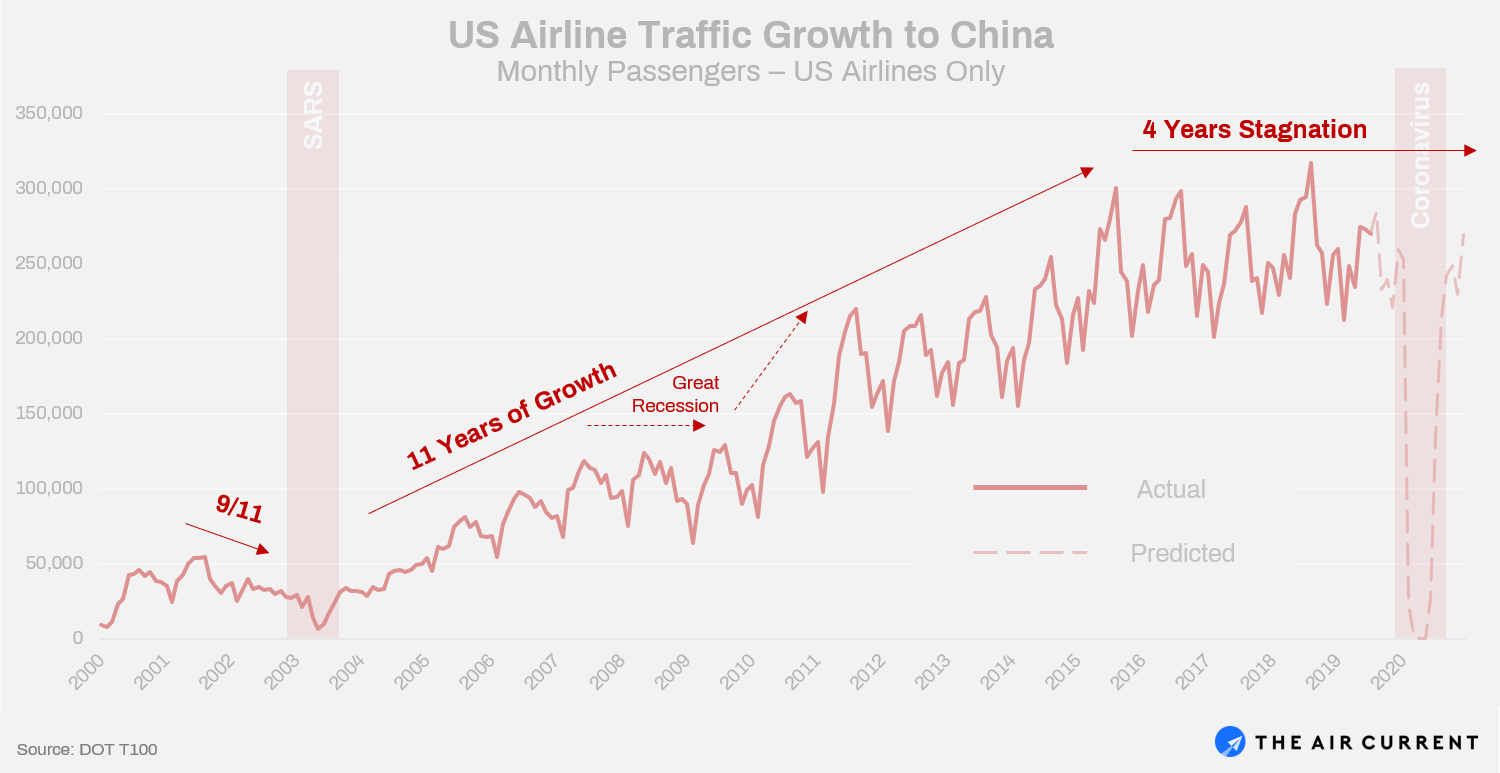

The historical context of the connection between U.S. and China is important to understanding how the market could recover from this latest outbreak. It has seen incredible growth over the past 20 years, increasing passenger numbers six-fold.

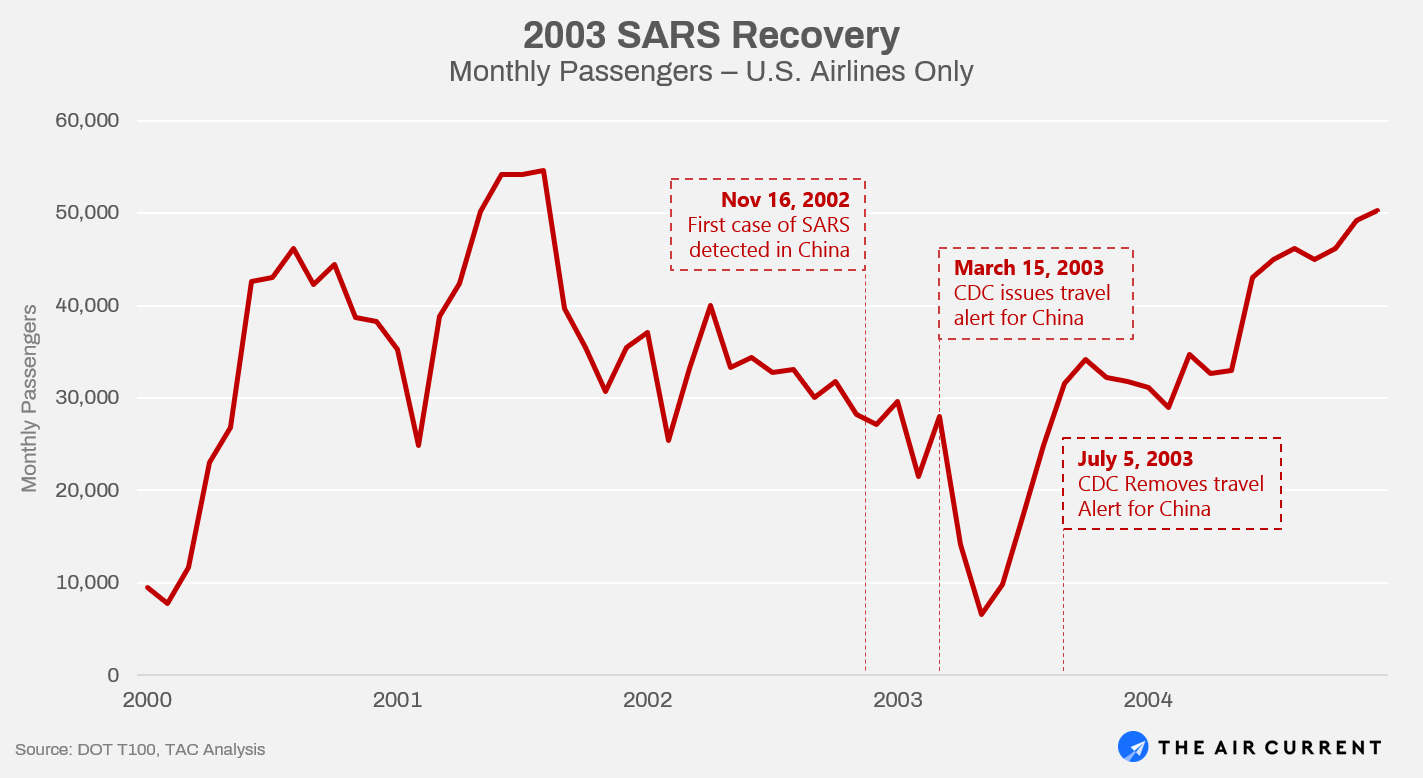

The SARS panic in 2003 was devastating to the market, however growing economic forces during the last 20 years have proven the outbreak to have been little more than a blip on the long-term trend of air travel growth. This is likely due to the fact that the SARS effect on demand was entirely exclusive to the hangover from the recession in 2001 and the September 11th attacks, and full recovery occurred within a year.

First detected in November 2002, SARS did not hit the public consciousness until mid-March 2003 with a global alert from the WHO. Traffic on U.S. carriers plummeted over 80%, but was never completely stopped as United continued reduced service to Beijing and Shanghai. By July of that year, however, the WHO declared SARS contained and travel alerts were removed shortly thereafter.

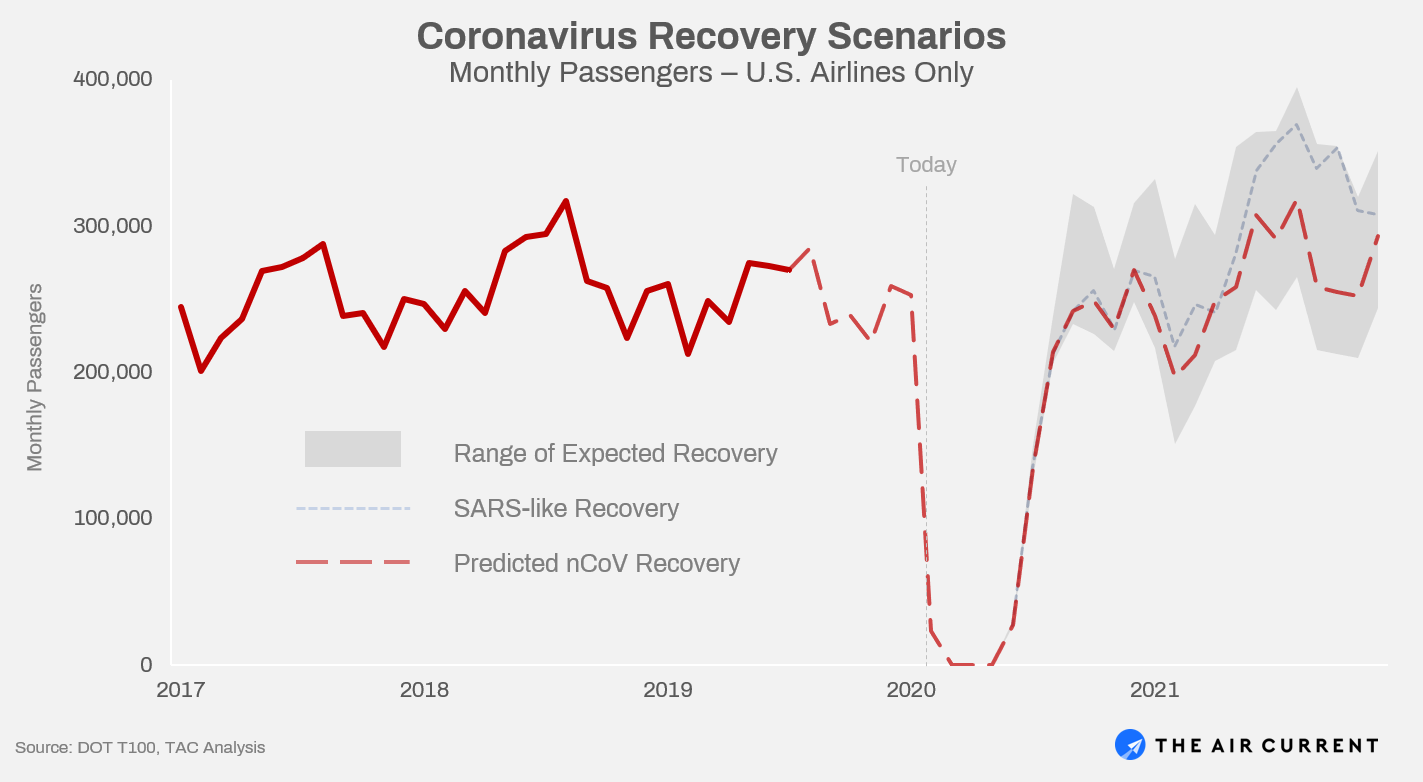

The recovery process was rapid, as demand and service returned to the U.S.-China corridor. In fact, by 2004 traffic had recovered to pre-SARS levels. Differences between SARS and 2019-nCoV, particularly around transmission and lethality, will likely drive different recovery timelines. However, once the green light is given, we expect traffic to follow a profile similar to that of the SARS recovery, yet within the context of the different overall market.

At the time of the SARS travel alerts, the global industry was already reeling from the September 11, 2001 attacks in the U.S. creating a lower bar for the post-SARS scare to show recovery. Traffic bounced back quickly from the outbreak, however it returned to an already depressed market from the 9/11 attacks and took until 2005 before the overall growth trend resumed.

What followed this recovery period was 11 years of unprecedented growth. This macro trend was recently broken in 2017 with four years of stagnation, and culminating in the already significantly reduced summer 2019 season as a result of the U.S./China trade dispute and slowing Chinese economic growth, according to IATA, in December capacity growth in domestic Chinese air travel surpassed demand by .8 percentage points.

The stage is now set for a potential coronavirus recovery which, even without the threat of the virus, will still be weighed down by the macro trends in the region. Considering the breadth of possibilities of recovery, and the historical profile of the SARS recovery, we are able to estimate the possible recovery scenarios.

Assuming a resumption of flights as early as May (to match the duration of the SARS travel alerts), we look for a similar recovery from the 2003 outbreak as demand returns to being driven by market forces.

While optimistic, the May return of service is based on a study by the National University of Singapore, the country with the second most cases of coronavirus. Researchers write, “there is reason to believe that the seasonal pattern of the novel coronavirus pneumonia…may sharply fall by May, when temperatures in China warm up.”

The upper bound of the growth range represents the traditional growth of the 2000’s returns in earnest, while the lower bound assumes the recent negative impacts from the trade disputes continue. Within this range of potential recovery, the SARS recovery profile stands out as growing at the top end of the range within a year of the resumption of flights. However, since this was also partially due to the 9/11 demand recovery, our estimate is adjusted. Assuming a resumption of flights in May, we expect the U.S.-China market to return to 2018 levels by mid-2021, and to return to the exclusive influence of the macro trends by that time.

Whether flights resume in May is yet to be seen, and entirely dependent upon the containment of the virus (or more specifically, containment of the panic). 2019-nCoV is its own animal, so to speak. When the green light is given to resume service is beyond the scope of this analysis, however the recovery of traffic beyond that point is well within.

As we saw in 2003, we expect traffic levels to return fairly quickly upon service being resumed to the region.

As much as we can estimate the speed of recovery once public confidence has been restored, the open question remains how long airports will remain closed to China. At some point, the lack of travel could begin having its own effects on the larger economies. Extended cancellations could further push this recovery beyond the SARS profile, especially if an entire summer season is lost.

Write to Courtney Miller at courtney@theaircurrent.com

Subscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention