The seventh in a series focusing on Boeing’s road to developing its next all-new commercial airplane.

On the other side of the grounding of the 737 Max, it is becoming increasingly unclear if Boeing’s new airplane development plans will still produce a twin-aisle jet — the 7K7 New Mid-Market Airplane (NMA) — or a smaller replacement for the 737 Max and 757.

The company’s development of the NMA exists somewhere between a real project and non-viable concept, trapped in a limbo that puts the company’s future product developments in deeply uncertain territory, according to more than a dozen interviews by The Air Current with hugely-influential customers, industry officials, project planners and senior Boeing leaders.

Related: The linchpin technology behind Boeing’s 797

Top executives at global airlines and lessors, including many who were thought to be likely large launch carriers for the NMA (which would eventually become the 797), have soured on the idea of Boeing’s 220 to 270-seat twin-aisle concept and are privately pushing for a successor to the 737 Max and the aging fleet of 757s.

Subscribe to TACBehind the scenes, Boeing has been recently briefing a small handful of U.S., European and leasing customers on an all-new aircraft — dubbed the Future Small Airplane (FSA) — whose first models would notionally be 180 to 210-seats. That’s larger than the 737 Max 8, which seats 162 passengers in a two-class configuration.

It’s not clear if plans for the FSA would supplant the NMA or quickly follow it, especially given the torrent of negative public perception that surrounds the 737 Max. Few details are known today about Boeing’s FSA concept, but the company’s strategy has long envisioned replacing the 737 Max 8 last in an extended series of development moves with new airplanes positioned above and below its most popular single-aisle variant.

Related: This is Boeing’s NMA

If the company has shifted its strategic focus away from NMA and toward a genuine replacement for the 737 Max, that edict has not flowed down to the teams designing the small twin-aisle. Inside Boeing, work on the NMA continues to advance. The company has revised some plans for its project milestones, including shifting the jet’s notional service entry to around 2026. The company is refining aspects of the design as Boeing needs to develop the manufacturing tooling, an early item that needs to be done well in advance of the jet’s production.

Even without the grounding of the Max, there has long been uncertainty about the business case that underpins Boeing’s plans for the NMA. There were signs immediately ahead of the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, the second of two 737 Max crashes, that board approval to offer the NMA was slipping deeper into 2019. The company had ramped up its engineering effort late last year with more than 1,000 people, but stopped short of both selecting an engine and giving approval to begin offering the 4,000 to 5,000 nautical mile-range airplane for sale.

Boeing declined to comment on internal NMA progress and any customer activity around the FSA.

However, the NMA in its current state remains in a paradox, according to company leaders and product planners. Boeing needs to develop and prove a suite of new manufacturing and design tools and technologies on the NMA at a low production rate — just over a dozen airplanes a month — before it can advance to running assembly lines for the smaller FSA that will need to produce more than a dozen jets each week.

The business case for developing the NMA has not closed, and there are worries inside Boeing that it never will given an uncertain market size and the price airlines are willing to pay for a small twin-aisle relative to the $15 billion price tag for development. With the FSA strategically dependent on the NMA’s business case, getting to a 737 replacement is mired in uncertainty.

Related: Suppliers at arm’s length as Boeing heads for 797 decision

According to a senior customer source familiar with NMA considerations, the business case had not closed when last presented at the last two company board of director’s meeting, including its most recent two-day confab on Oct. 20 and 21. Boeing Chief Executive Dennis Muilenburg confirmed as much on the company’s Wednesday third-quarter earnings call.

“We still are not at a decision point, nor are we ready to be at a decision point yet,” said Muilenburg of the NMA. The company’s “priority is a safe return to service for the Max,” he added and called the NMA a “project of interest.”

Subscribe to TACBut Boeing’s next step, seen by many as an increasingly important move to rebuild its market credibility after the 737 Max crisis, also faces leadership uncertainty after the firing of Boeing Commercial Airplanes CEO Kevin McAllister. McAllister’s dismissal and the business case murkiness of the NMA points to the uncertainty of the strategic stress that has permeated the company’s future direction.

McAllister, long a proponent of the NMA, was notified he was fired by the board on the evening of Oct. 21. The now ex-CEO attended the two-day San Antonio, Tex. board meeting and did not expect his dismissal, according to two people inside Boeing familiar with the events of the last week. Boeing Global Services boss Stan Deal was named as his successor.

Current and former Boeing executives also said the outcome of Muilenburg’s planned Wednesday, Oct. 29 and 30 testimony to the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation committee and the House Transportation and Infrastructure committee may create additional uncertainty around the company’s leadership structure. In short, the hearings may decide if he keeps his job.

The Tools Aren’t Ready

There is a real risk, say several NMA program staffers, that Boeing may sell itself on a business plan that overstates the benefit of its new digital development tools and overestimates the market on which it can derive a return on its investment in a small twin-aisle aircraft.

The concern is a repeat of the 787’s protracted development. Then-Boeing Commercial Airplanes Chief Executive Alan Mulally was under pressure in 2003 to cut the development cost of the advanced jet. Boeing came up with a plan to share costs with a cadre of suppliers through extensive outsourcing to make the numbers work — a $5 billion spending plan.

In December of the same year, the board members were blown away by the business case for the mostly-carbon fiber, heavily outsourced development and production plan. It would be a swift return on Boeing’s meager investment all while pushing the boundaries of material, manufacturing and systems technologies.

Related: Decade-old Boeing concept may get new life in dogfight with A321XLR

Despite skepticism by the board of Mulally’s optimistic projections, nevertheless the green light was given, one former Boeing director told the Wall Street Journal. The former director figured “It’s a wonderful plane. If we get half of that (projected) return, we would be delighted.” The airplane would end up delayed by three years, billions upon billions over budget and far more expensive to build than first forecast.

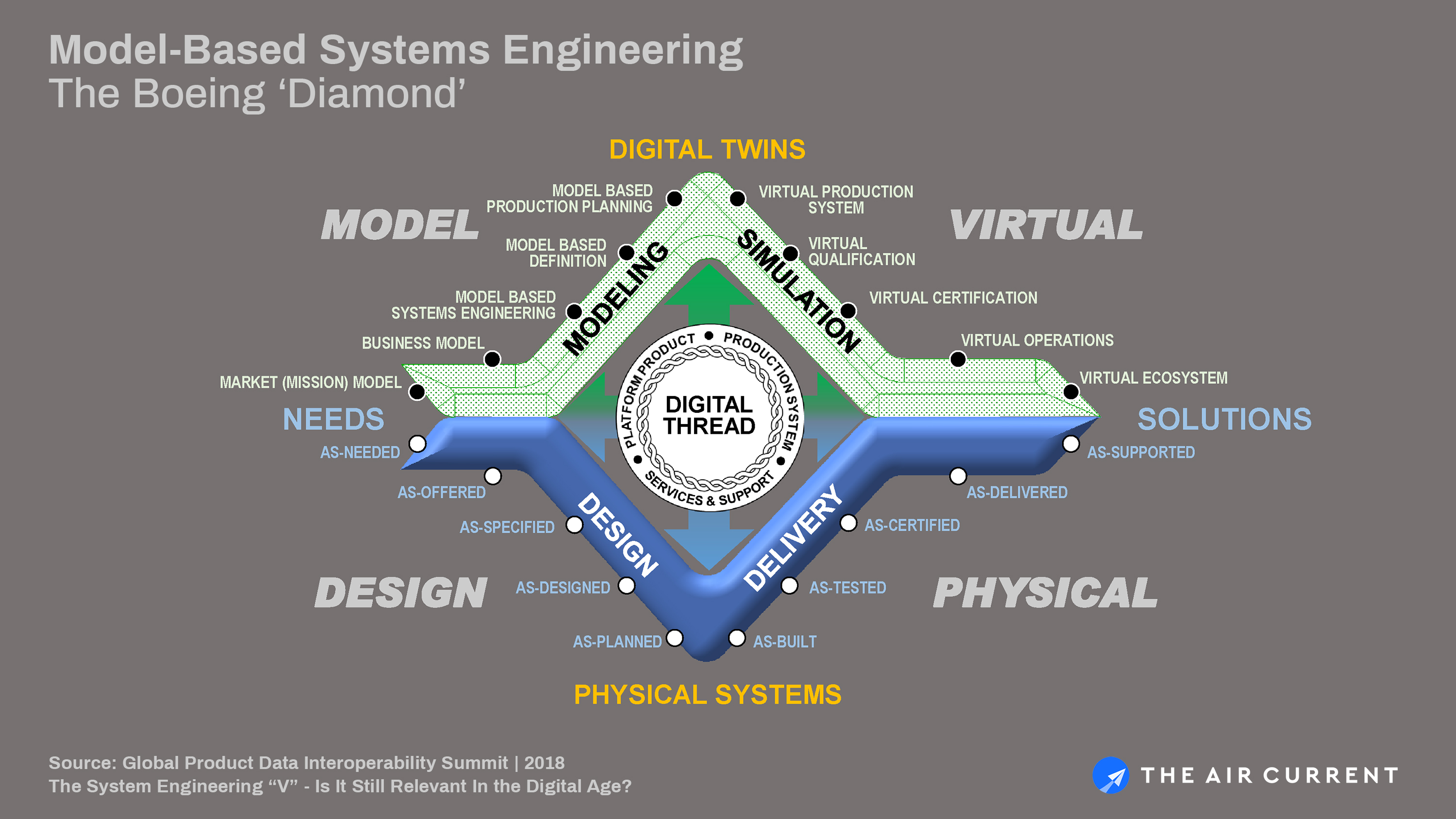

But with the not-ready-for primetime nature of many of the design tools, the technology strategy underpinning the NMA development has become increasingly hybridized, say those familiar with the planning. Boeing’s implementation of a full Model Based Systems Engineering plan will require only applying it in select areas of the jet’s development, relying on some legacy design systems like those first put to use on the 787. The newest tools would be aimed at the advances in manufacturing the company believes will make the business case close.

Related: Tracing the origins of Boeing’s ‘Diamond’ from Apollo to NMA

While still a lower-risk incremental step, said those familiar with the planning, the hybrid nature of the plan means it is only applicable for the life of the NMA. That creates a technology silo as Boeing makes patchwork connections to link the new digital tools to the old, as opposed to the company’s stated goal of deploying the tools it plans to use for the next 40 years, they added.

Muilenburg said last week, “We’re continuing to mature the business case. We’re continuing to invest in risk reduction around the production system of the future. And that continues to be a productive effort for us. So we’ll continue to leverage those investments. And when we’re ready to make a decision, we will.”

A 737 replacement

Any demise of the NMA program (in favor of the FSA), which has been discussed for years as a replacement for the 757 and larger 767, would trigger a wave of new tectonic changes within the commercial aircraft industry, including a likely truncated end of the besieged Boeing 737 Max, which has been grounded by global regulators since March following two crashes. From its first flight in 1967, the single-aisle 737 is the longest running commercial jet aircraft program in aviation history.

Boeing’s pending partnership with Embraer’s Commercial Aviation division and its engineering and manufacturing resources is seen as a means for rapidly bringing its next commercial airplane to market, whether that was centered on the larger NMA or smaller FSA and Embraer-derived concepts. But the specifics and timing of the arrival of such a new airplane are wholly uncertain given the ongoing Max grounding and regulatory environment that would be required to sign off on its certification.

Related: The end of Embraer and the beginning of Boeing Brasil Commercial

Prior to McAllister, the two previous commercial unit CEO administrations under Ray Conner and Jim Albaugh had both concluded that the strategic focus on an NMA should address the very top end of the 737 market first, not a push to replace aging 767s and A330s for medium range routes.

In the run-up to the impromptu launch of the 737 Max in 2011, Boeing considered a single-aisle concept called Y1 and three possible families for the 737 replacement, each with three variants. A one-for-one family from 125 to 180 seats, a category higher with 150 to 210-seats, or a third even-larger family spanning 175 to 225 seats. Boeing opted for the Max and the NMA, which evolved into a much larger and longer range aircraft.

Related: Airbus makes a case for disruptive stability in the A321XLR

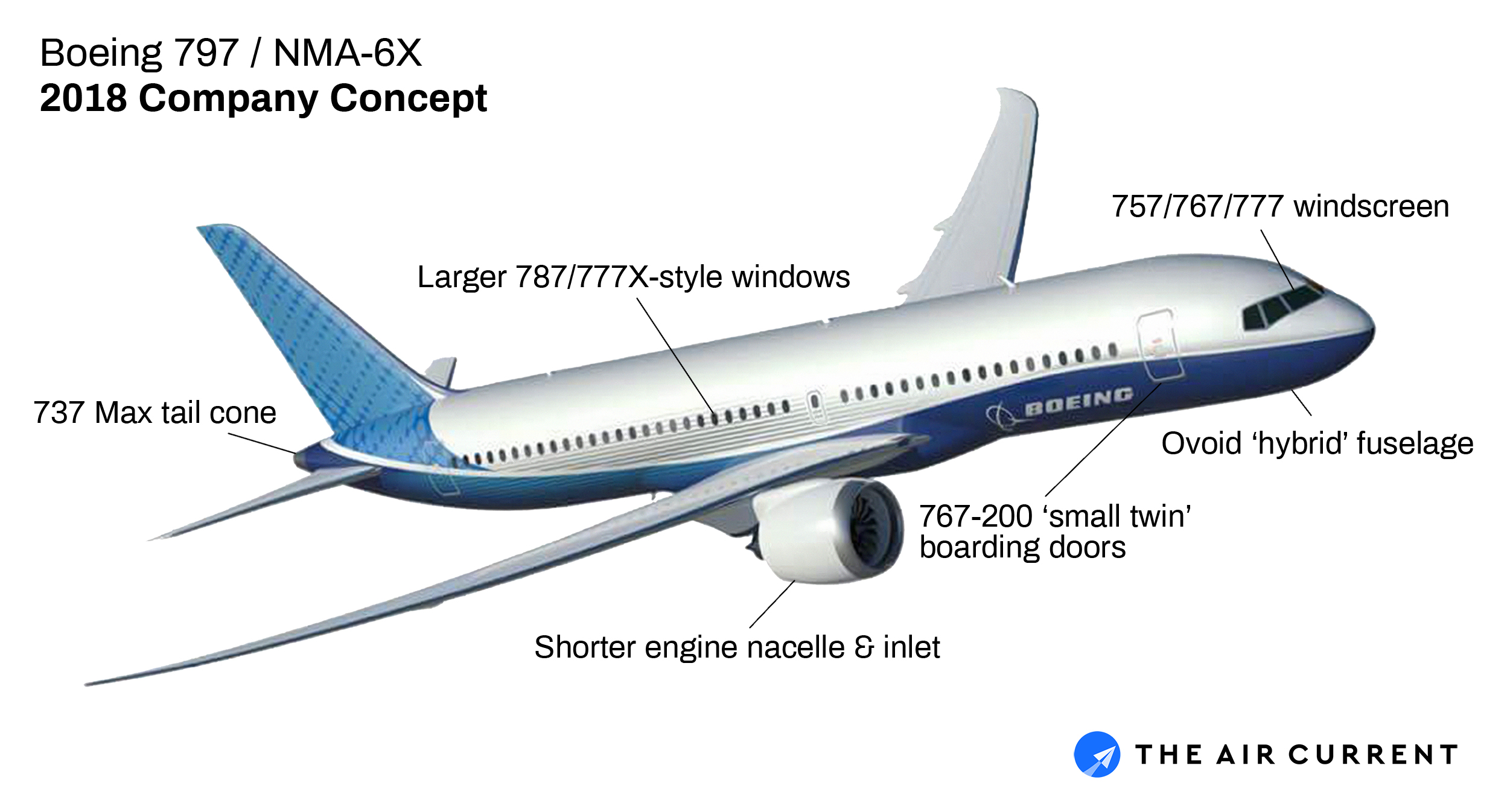

In the intervening years, the market reception to A321neo and subsequent A321XLR‘s arrival in 2023, however, had pushed Boeing’s focus away from first establishing a starting point in first replacing the aging fleet of single-aisle 757s and increasingly toward 767-300ERs, A330-200s and A330neo. Notionally, Boeing plans to first introduce the 268-seat NMA-7X before the 220-seat NMA-6X, according to David Joyce, President of GE Aviation.

Even with that focus shift, Randy Tinseth, Boeing Vice President of commercial airplane marketing in June anticipated the two-decade market for the NMA was still 4,000 and 5,000 airplanes. Yet, the balance of those aircraft was weighted toward the smaller of two NMA models, he said, reflecting on the nearly 4-to-1 split toward higher volume single-aisle jets in its overall 20-year forecast.

Related: Boeing collapses NMA and FSA into a single search for its next airplane

“The rationale for the NMA has not gone away,” said Aengus Kelly, Chief Executive of lessor AerCap, in a recent interview with The Air Current — assuming the business case can close. “The longer the wait, the more the A321XLR takes the market. That’s the tension Boeing is facing.” But Kelly said the 737 Max and its on-going grounding puts Boeing’s entire product strategy on hold. “You can’t really address that issue without addressing the most fundamental issue we’ve faced in a generation.”

Write to Jon Ostrower at jon@theaircurrent.com

Subscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention