Log-in here if you’re already a subscriber

Air safety reporting by The Air Current is provided without a subscription as a public service. Please subscribe to gain full access to all our scoops, in-depth reporting and analyses.

On Aug. 17, 2022, after a large Airbus A330neo carrier reported leaking high-pressure valves in the system that bleeds air off of the engines, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency issued an emergency airworthiness directive (AD) to operators of the widebody aircraft. Effective immediately, it prohibited flight crews from taking off in certain configurations, namely with air conditioning packs off, auxiliary power unit (APU) bleed air on, and/or engine bleed air off — configurations that some but not all A330neo operators were using to achieve higher performance on take-off.

Emergency ADs are relatively infrequent: EASA typically issues one to two dozen per year across all aircraft types, compared to 400 to 500 normal ADs. They are issued when an unsafe condition exists that requires immediate action. In this case, the emergency AD, which was adopted by the Federal Aviation Administration a day later, stated that leaking bleed system high-pressure valves could expose the downstream pressure regulating valve to damaging high pressure. Failure of the pressure regulating valve, it said, could lead to high pressure and temperatures in the downstream duct, potentially causing the duct to burst and leading to a loss of control of the airplane.

ADs tell operators what to do but they don’t always connect the dots, and neither the emergency AD nor the various ADs that superseded it explained the connection between taking off with “PACKS OFF”, “APU bleed ON” or “ENG bleed OFF” and leaking high-pressure valves. In fact, what the leaking valves had done was trigger a safety investigation within Airbus that discovered a hidden and potentially catastrophic flaw in the A330neo’s pneumatic system — the details of which have not been previously reported.

Seeking an explanation for the leaking valves, Airbus engineers turned to the company’s big data platform, Skywise, in search of clues. By comparing operational and sensor data, they were ultimately able to determine that in certain take-off configurations, the software in the bleed monitoring computer (BMC) — which controls the hot, high-pressure bleed air coming off the aircraft’s Rolls-Royce Trent 7000 engines — did not correctly control the high-pressure valve where it meters air from the engine’s high-pressure port. Excessive stress caused a failure of the valve’s clamping pin (or clip), leading to damage of the seal and subsequent leakage, which had the potential through a cascading failure sequence to result in this hot, high-pressure air escaping into the wing and causing major damage.

As soon as the issue was understood, Airbus informed EASA and recommended the emergency AD, choosing to accept any resulting operational disruptions rather than risk the possibility of a catastrophic accident while acting on a longer timescale. As additional fixes were developed, subsequent ADs over the next two years directed operators to replace the affected clips and eventually update the BMC software to correct its logic, which ultimately allowed for the initial operating and maintenance restrictions to be relaxed.

Historically, hidden failures like this one have been discovered primarily through the investigations that follow in the wake of serious incidents or accidents (the best-known example being the twin crashes in 2018 and 2019 of the Boeing 737 Max). What makes the A330neo case so significant for the entire aviation industry — including new entrants who are designing highly digital aircraft — is how data was used to uncover the failure before it resulted in harm to people or property.

After The Air Current approached Airbus with questions about the engineering investigation, the company made Ian Goodwin, director of flight safety – safety enhancement for Airbus Product Safety, available to discuss both the A330neo case and the company’s approach to leveraging data for safety more broadly.

The modern approach to designing and certifying aircraft requires engineers to predict the various ways in which their design might fail, estimate the likelihood of those failures and then implement mitigations for any unacceptable risks. Yet, as aircraft have become ever more complex, it has become increasingly challenging for design engineers and certification authorities to foresee all possible failures of a design across the full range of operating conditions it will encounter in the real world.

With Skywise — a product known best as a tool aimed at increasing operating efficiency for airlines and manufacturing efficiency for the plane maker — Airbus is demonstrating how its massive trove of data can help build a safety bridge between design and operations, yielding insights that support established processes for ensuring continued airworthiness.

“Everybody talks about data,” explained Goodwin, “but it’s about getting data and turning it into intelligence.” Data is not a replacement for human analysis, he said, but “it’s a really useful tool, it enables us to see what’s happening, and it supports the decision-making process.”

Seeing the big picture

Airbus launched its Skywise platform at the 2017 Paris Air Show in collaboration with Palantir Technologies, a specialist in big data analytics. (Former Airbus Commercial CEO Fabrice Brégier served as Palantir France’s chairman from 2018 to 2024.) Skywise integrates data from many different sources, including the wealth of flight and health-and-usage data that is collected onboard modern aircraft, which is around 500 gigabytes per day for the A330neo and up to 1 terabyte per day for latest generation aircraft like the A350. The core platform provides participating airlines with a variety of digital tools and is used as the basis for additional offerings, including predictive maintenance and health monitoring.

Any large-scale collection of data is invariably associated with sensitivities around who will use that data and for what purposes. Because participation in Skywise is wholly voluntary, the success of the platform relies on airlines trusting in what Airbus calls its “shared value” business model, meaning that both the airlines and manufacturer benefit from the sharing of operational data. Safety is not the only pillar of that business model, but it is a substantial piece of it.

“Everything about sharing the data is voluntary, because if the airline doesn’t sign up to agree with it, then the data is not shared,” said Goodwin, emphasizing the importance of using operational data for the goal of enhancing safety. “We don’t want to get things turned off, where airlines go, ‘Stop, we’re not going to share the data because you used it for the wrong reasons.’”

Today, Airbus reports that more than 11,900 aircraft are connected to the platform (some users analyze data from other manufacturers’ aircraft with the help of Skywise as well). As more airlines have signed on to Skywise, sharing ever more data, the platform has become increasingly valuable as a tool for analysis and predictive modeling, including for safety purposes.

“With more data, we can have a look at a bigger picture,” said Goodwin. “We can prioritize, and prioritization in operations and safety is very important. So if we get an issue that’s identified, we can identify what the safety risk is, we can identify what the exposure is, then we can prioritize on the key issues.” Goodwin said the highest priority risks are those associated with what he described as “the big four”: loss of control in flight, controlled flight into terrain, mid-air collisions and runway excursions.

When one out of a million happens once a month

In the A330neo example, Airbus was able to identify and address a design problem before it resulted in an incident or accident — the type of proactive safety success that the aviation industry has long aspired to. But Skywise has also been used in support of formal investigations into serious incidents.

One of these incidents took place in April 2022, when a TAP Air Portugal A320 equipped with two CFM56 engines was attempting to land with a gusty crosswind at Copenhagen Airport in Denmark. The aircraft touched down on runway 30 and deployed its thrust reversers, which use four blocker doors for each engine to change the direction of engine fan air and assist in braking the aircraft.

The standard operating procedure (SOP) for landing is that once thrust reversers have deployed, the crew must perform a full-stop landing. However, the aircraft commander (as he was described in the accident report) was uncomfortable with the aircraft’s attitude and opted to abort the landing and perform a go-around.

As he moved the thrust levers fully forward, the blocker doors for the right-hand (No. 2) engine thrust reverser stowed and locked, and the No. 2 engine started accelerating to take-off and go-around thrust, as expected. However, the blocker doors for the left-hand (No. 1) engine thrust reverser did not stow, and the No. 1 engine stayed at idle. The crew had difficulty controlling the aircraft during the go-around, but were ultimately able to climb, shut down the No. 1 engine, and return for a single-engine approach and safe landing.

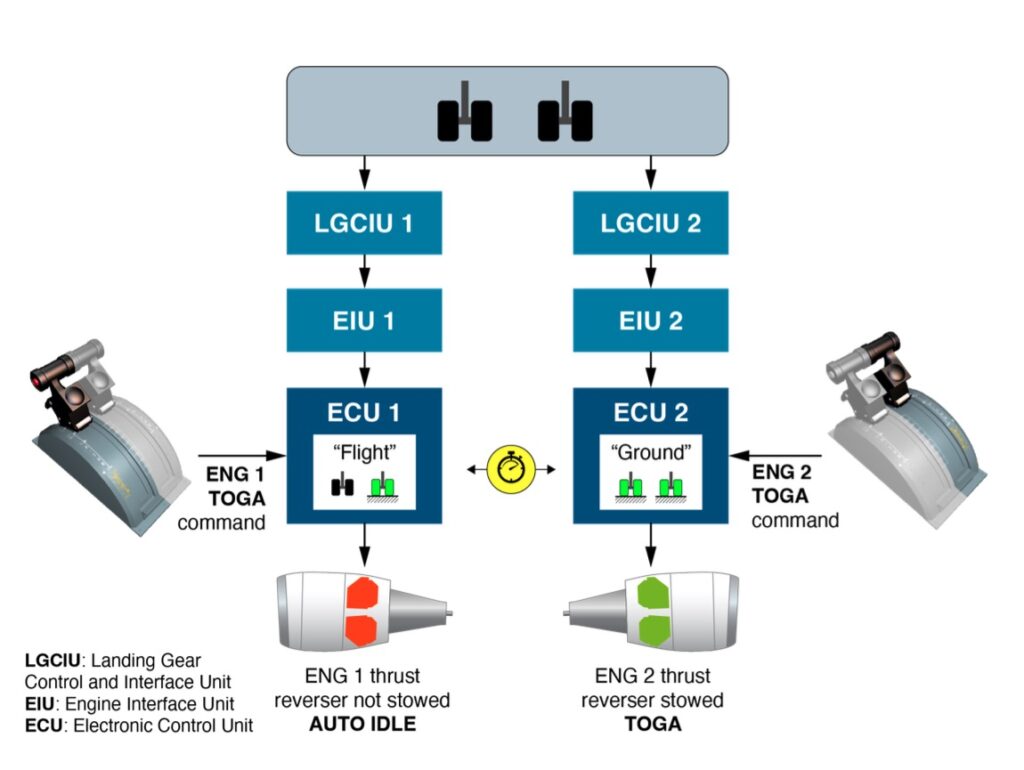

It was not immediately obvious why the No. 2 thrust reverser stowed while the No. 1 thrust reverser did not, but the investigation ultimately traced the likely cause to the software logic in the CFM56’s electronic control unit (ECU). When the thrust levers are moved forward from the reverse position, each engine’s ECU computes a “ground” or “flight” status based on the compression of the main landing gear on its respective side, and a “ground” status is required to start the stow sequence. But these computations happen independently between the two engines, and the timing between them may be slightly off due to computational delays and small misalignments of the thrust levers.

In the TAP incident, the ECU for the No. 2 engine computed a “ground” status and commanded the thrust reverser to stow and lock. That engine then spooled up normally. However, a short asynchronism combined with a bounce of the left landing gear meant that the ECU for the No. 1 engine computed a “flight” status and did not successfully command its thrust reverser to stow. The ECU’s automatic idle function — meant to protect against generation of excessive reverse thrust in flight — detected that the thrust reverser remained deployed and prevented engine No. 1 from spooling up.

In interviews with investigators, both the commander and first officer said they were aware of the SOP that required them to land after selecting reverse thrust. However, neither of them had a clear memory of selecting reverse thrust and both were convinced that selecting take-off and go-around thrust would cause the thrust reversers to stow — not an unreasonable assumption, considering that a review of other Airbus models found that only the ECUs for CFM56 engines used this particular logic.

The Danish Accident Investigation Board concluded that the commander’s decision to abort the landing was not an intentional violation of the SOP, but rather a “mistake” based on incorrect perception and incomplete awareness of the importance of complying with the SOP.

By delving into Skywise data, Airbus was able to determine that he wasn’t alone.

According to the final report on the incident, analysis of 3.4 million flights by 31 operators indicated that an aborted landing/go-around after thrust reverser selection had occurred on approximately one out of one million flights across the entire A320 family (with four different engine configurations across Ceo and Neo models). While one in a million might seem vanishingly rare, translating this rate to the entire fleet and utilization of A320 aircraft in service suggested that such aborted landings were occurring at an average rate of one per month.

That high frequency prompted Airbus to move forward with a modification of the ECU software for the CFM56-5B (the most common CFM56-5 variant in service) to enhance the stow logic in case of a rejected landing with thrust reversers already selected. The company said the modification, targeted for 2025, will prevent a recurrence of this type of event. Airbus also embarked on an education campaign for flight crews, which included revising the flight crew operating manual and producing articles and a training video to raise awareness of the issue.

Closing the loop

In the A330neo and A320 cases described here, Skywise was used as a resource by investigators who already knew what questions they wanted to answer: Why are these high-pressure valves leaking? How often do pilots perform a go-around after selecting reverse thrust? In an ideal future, Skywise data could also be a source of safety alerting by using artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) to identify discrepancies before they create a risk to safety or a requirement to ground the aircraft for maintenance, thus enhancing both safety and operational efficiency beyond existing uses of data for predictive and preventative maintenance.

“In the future world where we want to go is potentially [using] artificial intelligence, machine learning, to pick that thing and say, ‘Hang on, that’s not right based on it’s an outlier in all the data we’ve seen, and therefore it’s something you need to look into,’” Goodwin said. However, deploying any such AI/ML alerting function must be done with care to ensure that it is sufficiently reliable and actually providing good information.

In the meantime, it is mostly up to humans to identify so-called “weak signals,” which are those occurrences and conditions that knowledgeable observers recognize as not quite right. According to Goodwin, many of the weak signals that Airbus currently uses to identify safety issues arrive via reports from the field — such as those leaking bleed system high-pressure valves on the A330neo — which is why “reporting events is so important,” he said.

This is something that EASA emphasizes in a recently revised safety information bulletin (SIB), which specifically addresses the reporting of occurrences involving human interventions in large airplanes used for commercial air transport. The SIB explains that aircraft manufacturers make certain assumptions about flight crew behavior when certifying their aircraft and need to identify any deviations from these assumptions in an operational context.

“The effectiveness of the continuing airworthiness system depends on the [manufacturer] being made aware by the operators, in a systematic and comprehensive way, of occurrences/events or trends that may reveal shortcomings which may warrant evaluation of flight deck design, operating procedures, training, or a combination of the three,” the SIB states.

To clarify the expectations associated with mandatory reporting, the SIB gives numerous examples of the types of interventions that should be reported, encompassing errors of perception, decision-making, response execution and communication. These include things like the flight crew failing to detect a visual or aural signal, reaching for the wrong knob or button, or performing actions too early, too late or out of sequence. In isolation, these actions might simply be chalked up to pilot error, but any of them could also be the weak signal that leads to uncovering more systemic problems with aircraft design or training.

“When you talk about safety, you always look at closing the loop,” said Goodwin. “It’s all very well putting something in service, but if we can then monitor how effective it is, we can see whether we’ve done … the right thing at the right time with the right implementation. And that’s the other advantage of data — it enables us to do that to close the loop.”

Write to Elan Head at elan@theaircurrent.com

Subscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention