Log-in here if you’re already a subscriber

The stage for the current debate over airline pilot qualifications was set in a darkened cockpit over western New York on the night of February 12, 2009.

Five minutes before the Colgan Air Bombardier Q400 operating as Continental Connection Flight 3407 stalled and crashed while on approach to Buffalo-Niagara International Airport, killing all 49 people on board and one person on the ground, the captain and first officer were deep into a conversation that had nothing to do with the task at hand. The aircraft was just a few thousand feet over the ground at the time, well below the level at which sterile cockpit procedures should have taken effect. The National Transportation Safety Board determined that the captain, by enabling the conversation, created an environment that impeded timely error detection, contributing to his startled and inappropriate response to stick shaker activation a few minutes later.

Both pilots were fatigued, and any extraneous conversation at that point probably would have posed the same deadly distraction. But it so happened that the content of their conversation was tragically poignant and, ultimately, highly consequential. In a damning public transcript of the cockpit voice recorder, families of the victims of Flight 3407 could read how the first officer, as she watched ice form on the wings and windshield, remarked on how little exposure she had received to icing and actual instrument meteorological conditions in the 1,600 hours of flight time she had logged before coming to Colgan (she had over 2,200 hours at the time of the crash).

Related: Pilot shortage solutions are plentiful but politically improbable

The captain who was about to make an unfathomable mistake — repeatedly pulling aft on the control column as the stick shaker and stick pusher activated in turn, rather than pushing forward — replied that he didn’t even have 1,600 hours when he came on board (he was then up to around 3,400). “As a matter of fact I got hired with about 625 hours here,” he said. “Oh wow,” the first officer replied, “that’s not much.” These seemingly incriminating words may explain why an accident that occurred with two reasonably high-time pilots at the controls became the impetus for keeping low-time pilots out of airline cockpits.

The so-called “1,500-hour rule” was not the only piece of rulemaking to come out of the Colgan crash, but it is the one that is now receiving the most attention as U.S. regional airlines struggle to hire enough pilots. Mandated by Congress, the Federal Aviation Administration rule dramatically increased experience requirements for Part 121 airline first officers, disrupting a business model that had previously exploited an ample supply of low-time pilots. With regionals now pushing for changes or exemptions to the rule, a heated but largely philosophical discussion has arisen over what makes for a “good” airline pilot, and how flight time maps to safety outcomes.

Subscribe to TACYet, this narrow focus on pilot flight time as a proxy for safety misses the principal lessons of the Colgan crash. There is not much evidence linking flight hours to accidents and there likely never will be, because pilots and flight experience are infinitely variable. At the same time, the 1,500-hour rule may have had some indirect safety benefits by empowering pilots to push back on commercial pressure. Rather than focusing exclusively on pilot qualification, it may be more productive to examine the system in which these pilots operate, and whether the more direct safety improvements that resulted from Flight 3407 can accommodate a reduction in flight hours for the pilot in the right seat.

An industry turning point

The public anger that erupted in the wake of the Colgan crash was not primarily directed at the two tired pilots who made a series of boneheaded mistakes. Rather, it was an indictment of a regional airline industry that was cutting corners and the regulator that had failed to rein it in. The investigation revealed that the captain had a history of failed checkrides, and while he had concealed some of these from his employer, Colgan had largely overlooked his unsatisfactory performance on multiple company training events.

A former Colgan pilot interviewed by PBS Frontline described a company that had expanded rapidly, had only recently acquired Q400s, and wanted to “get the job done at all costs”. That pilot said he had been thrown into the captain’s seat of the Q400 immediately after his type training, which consisted of a seven-day ground school and 10 simulator sessions. “None of us had ever operated this airplane before, and a lot of the first officers that were being hired for this airframe had very little time, you know, in the sense that I flew with first officers that had 300 hours, 350 hours,” he recalled.

Outsiders were shocked to learn that many pilots who commuted long distances for work were not provided with suitable rest facilities, instead relying on shared, self-funded apartments called “crash pads” to grab whatever sleep they could. Neither of the pilots on Flight 3407 had arranged for a crash pad, and instead tried to make up for lost sleep through illicit naps in the crew room. The NTSB concluded that the captain had experienced chronic sleep loss, and both he and the first officer had experienced interrupted and poor-quality sleep during the 24 hours before the accident. Another Colgan pilot told Frontline that on one occasion when he claimed fatigue after several 16-hour duty days, company leadership suggested that he falsify duty time records in order to complete a last flight.

The first officer’s poverty wages were another source of outrage. During the accident flight, she told the captain she had made less than $16,000 during her first year at Colgan and referenced her low pay and perceived poor treatment on multiple occasions. “I feel like Colgan walks all over me. This company treats me like crap so much,” she said. She was evidently sick and sniffling, but cognizant of the fact that if she called in sick, she’d have to pay to put herself in a hotel. “We’ll see how it feels flying,” she told the captain as they were waiting for their takeoff clearance. “I could always call in tomorrow, at least I’m in a hotel on the company’s buck, but we’ll see.”

In August 2010, six months after the NTSB issued its report on Flight 3407, Congress passed Public Law 111-216, a sweeping reform package that addressed many of the NTSB’s recommendations around the crash. Among other things, the law directed the FAA to create a comprehensive pilot records database to include each pilot’s training records, and required air carriers to evaluate these records before allowing anyone to begin service as a pilot. It charged the FAA with overhauling its flight and duty time regulations and required each Part 121 air carrier to submit a fatigue risk management plan. The FAA was also told to require safety management systems of Part 121 operators and help them implement flight operational quality assurance programs.

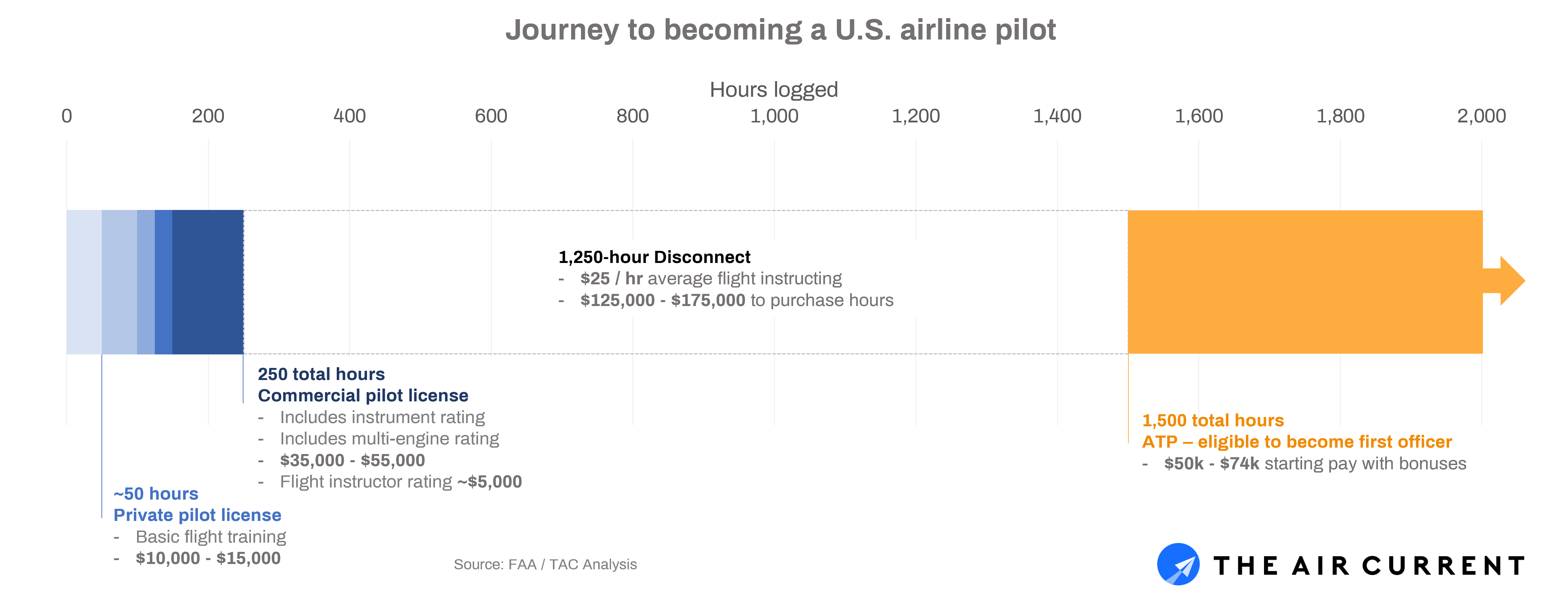

The law further required the FAA to study and conduct rulemaking around many of the crew training and qualification issues that were implicated in the Colgan and other regional airline crashes: things like stall and upset recognition and recovery training, remedial training, and professional development. Finally, the law mandated that within three years of its effective date, all flight crewmembers in Part 121 operations hold an ATP, and that ATP certification be revised to better prepare pilots for air carrier operations, adverse weather conditions and high-altitude flying. Previously, first officers needed only a commercial pilot certificate with an instrument rating, which could be obtained with as few as 190 flight hours through a Part 141 school.

Writing the 1,500-hour rule

Most of the mandates in Public Law 111-216 can be traced directly to recommendations made by the NTSB, but there was one notable exception: the explicit requirement that all ATP holders have at least 1,500 hours, unless the FAA determines that “allowing a pilot to take specific academic training courses will enhance safety more than requiring the pilot to fully comply with the flight hours requirement.” None of the 25 new recommendations issued by the NTSB after the Colgan crash addressed pilot time per se. Neither did any of the recommendations associated with three other accidents that are often cited as evidence of a regional airline industry that had run amok: October 2004 crashes by Pinnacle Airlines and Corporate Airlines in Jefferson City and Kirksville, Missouri; and the August 2006 crash of Comair Flight 5191 in Lexington, Kentucky.

In July 2013, following extensive public consultation, the FAA published the final rule establishing the pilot certification and qualification requirements for Part 121 air carriers that exist today. The rule codified the 1,500-hour minimum dictated by Congress, permitting exceptions only for pilots who hold an associate’s or bachelor’s degree with an aviation major — who can qualify for a restricted ATP with 1,000 and 1,250 hours of flight time, respectively — and military-trained pilots, who need just 750 hours for a restricted ATP.

The rule also requires that pilots have at least 1,000 hours in air carrier operations before upgrading to captain, with the aim of ensuring that first officers complete a full year of Part 121 operational experience before assuming the authority and responsibility of pilot in command. Although less well known than the 1,500-hour rule, this requirement has become another obstacle to keeping regional cockpits staffed as mainline carriers have gone on a post-COVID hiring spree.

Related: Impact of the pilot shortage will cascade far beyond empty cockpits

Aviation accidents are rare and multifaceted events, which makes them difficult to analyze statistically. In 2012, as it worked on its final rule for Part 121 pilot certification, the FAA attempted to analyze what effect this specific rulemaking might have had on accidents that occurred in the previous decade. The agency identified four Part 121 accidents resulting in two fatalities in which the additional flight experience required by the rule might have achieved a “moderate-to-high” (roughly 55%) reduction in the likelihood of the accident.

“Some of the other elements of the rulemaking, such as screening pilot applicants, preparing pilots better for the complex environment of air carrier operations, better training in stall recognition, and the importance of professionalism would have had some minimal chance of influencing additional accident outcomes,” the FAA wrote. The agency estimated that the rulemaking would have reduced the likelihood of the Colgan crash only “moderately” (by around 35%).

The long-running Pilot Source Study has attempted to quantify whether higher-time pilots are better prepared for airline operations by analyzing pilot training records from regional airlines across multiple variables. Its most recent (2018) study of nearly 10,000 pilots found that pilots with 1,500 or fewer hours — including military and institutional restricted ATP holders — actually tended to be more successful in their initial training than higher-time pilots, consistent with the findings of earlier studies that were submitted to the FAA for consideration.

In the discussion of its final rule, the FAA confirmed that it “found no quantifiable relationship between the 1,500-hour requirement and airplane accidents.” Yet, because of the language adopted by Congress, the 1,500-hour requirement would become law regardless of FAA action.

Looking beyond pilot qualification

Republic Airways is now asking the FAA to grant the 750-hour credit afforded to military pilots to graduates of its own pilot training program, arguing that it can exceed the safety standards of the military restricted ATP by training civilian pilots from the ground up specifically for Part 121 operations. The comments in the docket for its petition reflect much passionate debate: whether military flight training is inherently superior to civilian training, whether low-time civilian flight instructors are cultivating exceptional awareness and reflexes or simply repeating the same hour in the pattern 1,500 times, whether any structured training program can truly substitute for hours in the air, and whether any amount of stick-and-rudder time in an analog single-pilot aircraft can adequately prepare pilots for multi-crew operations in a highly automated cockpit.

Because it is challenging to establish causal links between safety interventions and outcomes, most of the safety arguments in favor of the 1,500-hour rule rely on correlation. In comments opposing Republic Airways’ exemption petition, Air Line Pilots Association, International (ALPA) points out that since 2010, there has been a 99.8% reduction in Part 121 passenger airline accident fatalities compared to the preceding two decades, and only one passenger fatality in a Part 121 operation where pilot performance was found to be contributing. “Pilot certification rules were the major part of a package of safety improvements as well as rule changes that work together and none of them should be reduced or undone,” the union stated.

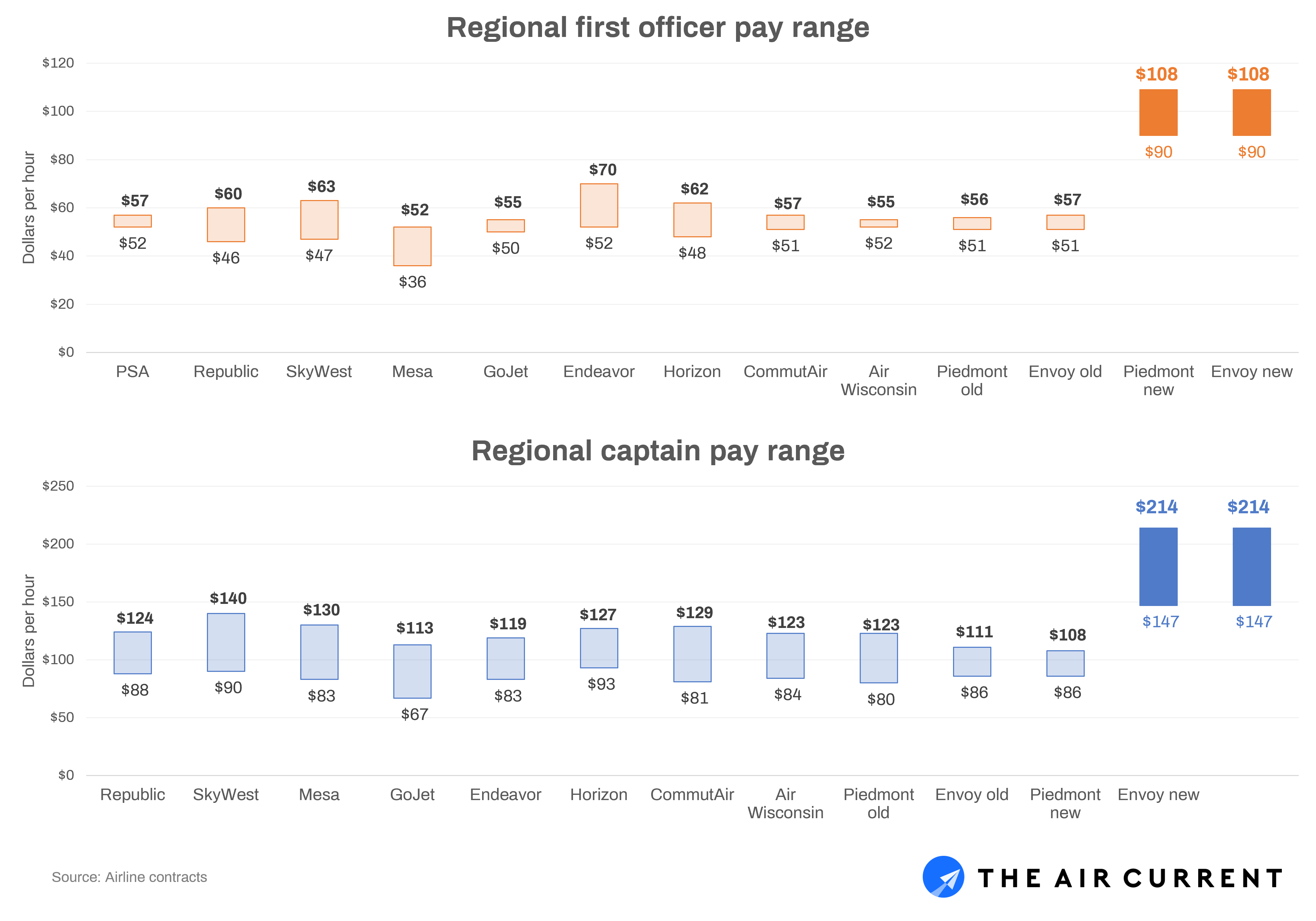

In ALPA’s assessment, Republic is “proposing that safety requirements be reduced in order to attract ‘cheap’ pilots.” The economic argument runs both ways, however, because ALPA’s members have clearly benefited from the scarcity of Part 121-eligible pilots created by the 1,500-hour rule. In June, American Airlines’ regional subsidiaries, Envoy Air and Piedmont Airlines, announced plans to nearly double pilot pay in an effort to staff their flight decks, dramatically reshaping the industry’s economics. In 2009, starting pay for first officers at regional airlines was around $21 per flight hour (or $30 when adjusted for inflation). Under their new contracts, Envoy and Piedmont’s first officer pay starts at $90, which can translate to as much as $90,000 for a pilot’s first year.

Each side in the present debate is condemning the other’s greed while emphasizing its own abiding concern for safety. Yet, safety and economics are intertwined in complex ways. Low-time pilots who are readily replaceable may be more hesitant to voice safety concerns and more susceptible to pressure. They may work for wages that make it financially prohibitive to call in sick or secure a good night’s sleep. At the same time, an airline that directs a disproportionate share of its revenue toward pilots will have less money available for other things that contribute to safety, including aircraft upgrades, maintenance and infrastructure improvements. Consideration of these second-order effects gets lost when the focus is strictly on pilot time and training.

Related: The pilot shortage is spreading beyond the regional airlines

If it is true, as regional airlines now claim, that the 1,500-hour rule has created an insurmountable barrier to keeping planes fully staffed, then we should not be evaluating potential solutions through the lens of pilot qualification alone. Rather, we should consider what negative safety pressures might result from disrupting the new status quo, and whether the system that emerged after the Colgan crash is robust enough to withstand them. Compared to 2009, the industry now operates with enhanced pilot screening, training, fatigue management and oversight. Are these improvements sufficient to resist the Colgan-era corner cutting that was facilitated by a plentiful supply of cheap pilots? And if not, what additional changes to the system would erect the necessary guardrails?

It is worth noting that there is one constituency that has absolutely not benefited from Part 121 reform, and that is low-time U.S. pilots themselves. Bridging the 1,250-hour gap between a commercial pilot certificate and an ATP is now a more fraught process than ever, and pilots must largely negotiate it on their own, often while saddled with crushing student loans. This suggests that low-time pilots are still vulnerable to exploitation in ways that compromise safety, only in corners of the industry — such as the Part 135 commuter and on-demand world — that are less visible.

We might also question whether the selection process created by this new system is in the industry’s long-term interest. Setting aside the military route, pilot careers today are most accessible to candidates who are either independently wealthy, or willing to endure several years of struggle and privation in pursuit of an uncertain reward. Lots of smart, capable people simply have better options.

Write to Elan Head at elan@theaircurrent.com

Subscribe to TACSubscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention