The seeds of an intensifying crisis in 2019 with the planet’s most popular commercial airliner may have been planted more than a half-century ago.

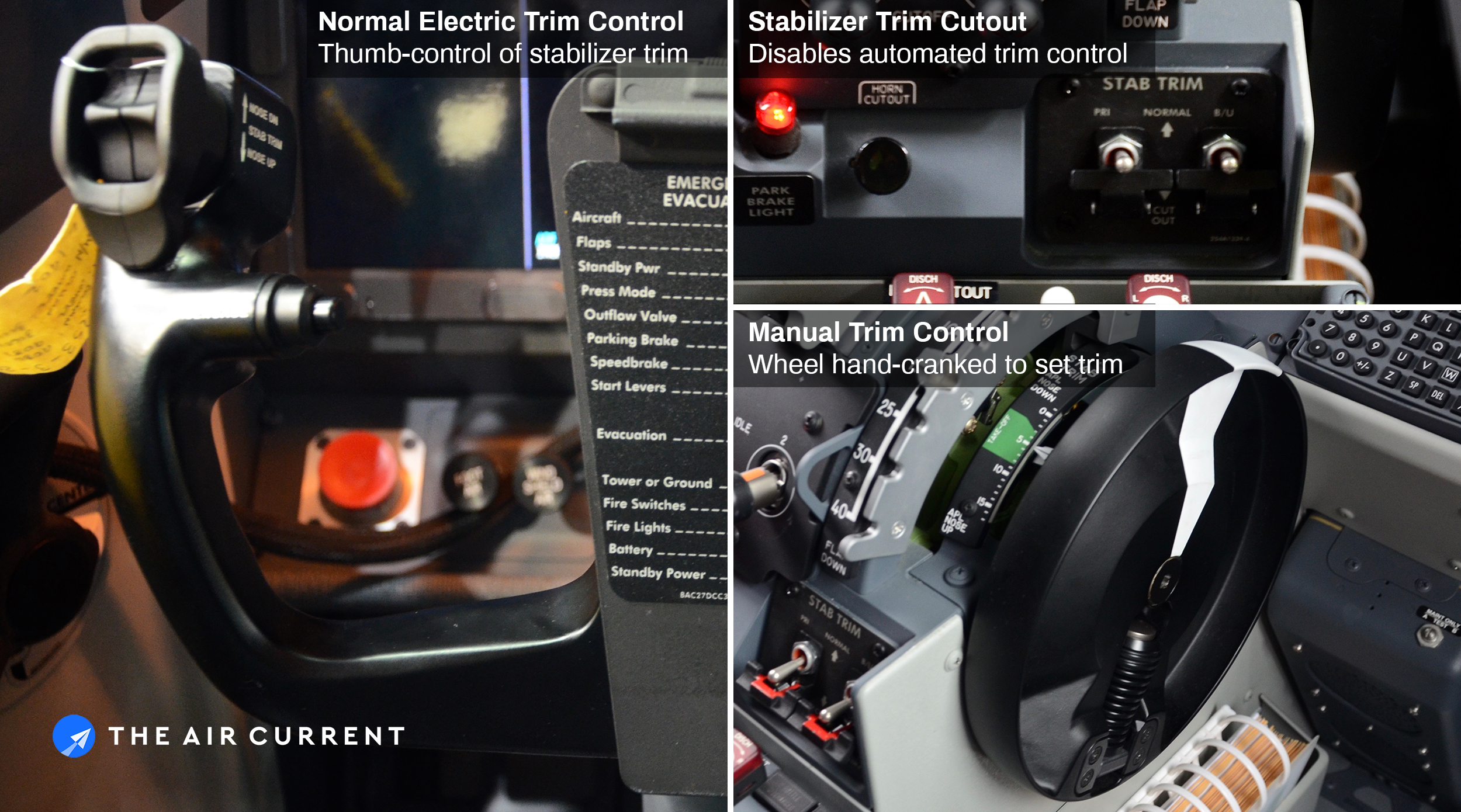

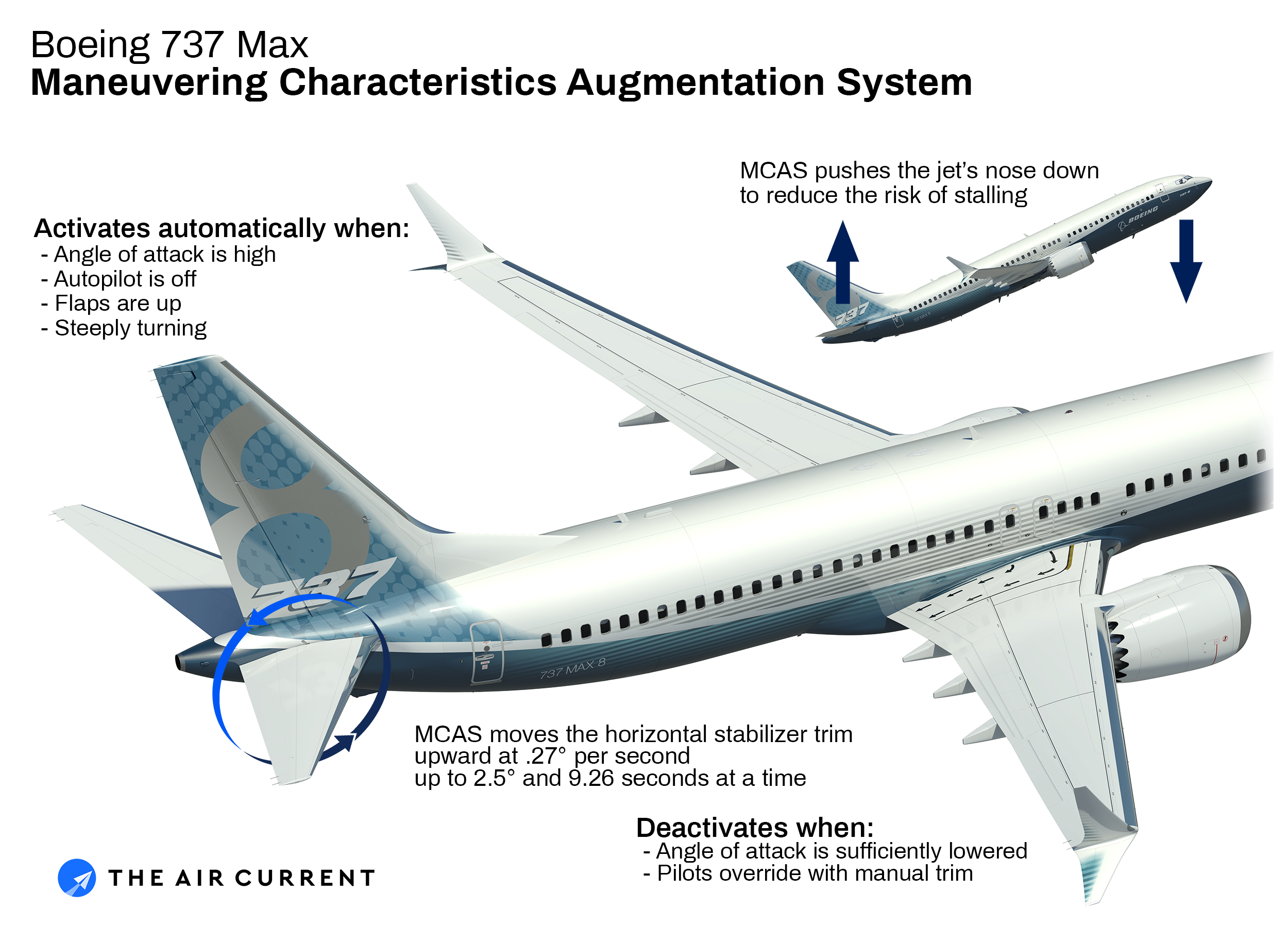

Five months after the crash of Lion Air 610, every Boeing 737 Max-trained pilot on the planet was familiar with the MCAS system. They knew how it worked and knew how to disable it should they find it behaving in a way that put their airplane in danger. Flipping two cut-out switches would be sufficient, according to the Boeing guidance as part of the memorized checklist to troubleshoot errant movement of the horizontal stabilizer trim. Then crews would manually hand crank the jet’s trim wheel to right the nose. At least initially, the crew of Ethiopian 302 did just that, according to the preliminary report into the crash released Thursday.

The recovery effort didn’t succeed and the trim wheel didn’t raise the jet’s nose. According to the 33 page report, the crew reactivated the electronic trim controls, causing the MCAS system to activate and push the jet’s nose down for a fourth and final time. With little altitude to recover, the 737 Max impacted the ground near Bishoftu, Ethiopia, killing all 157 aboard. The crash sparked the global grounding of the 737 Max days later.

Related: What is the Boeing 737 Max Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System?

The non-responsive trim wheel and the crew’s initial by-the-book efforts to save aircraft are expected to be an increasing focus of the myriad of inquiries into the 737 Max and its automated flight control system, according to air safety experts. But a vestigial design idiosyncrasy in the 737 may offer one clear explanation according to a former Boeing flight controls engineer, Peter Lemme, along with the procedures for recovering a badly configured 737 horizontal stabilizer that date to the early 1980s and before.

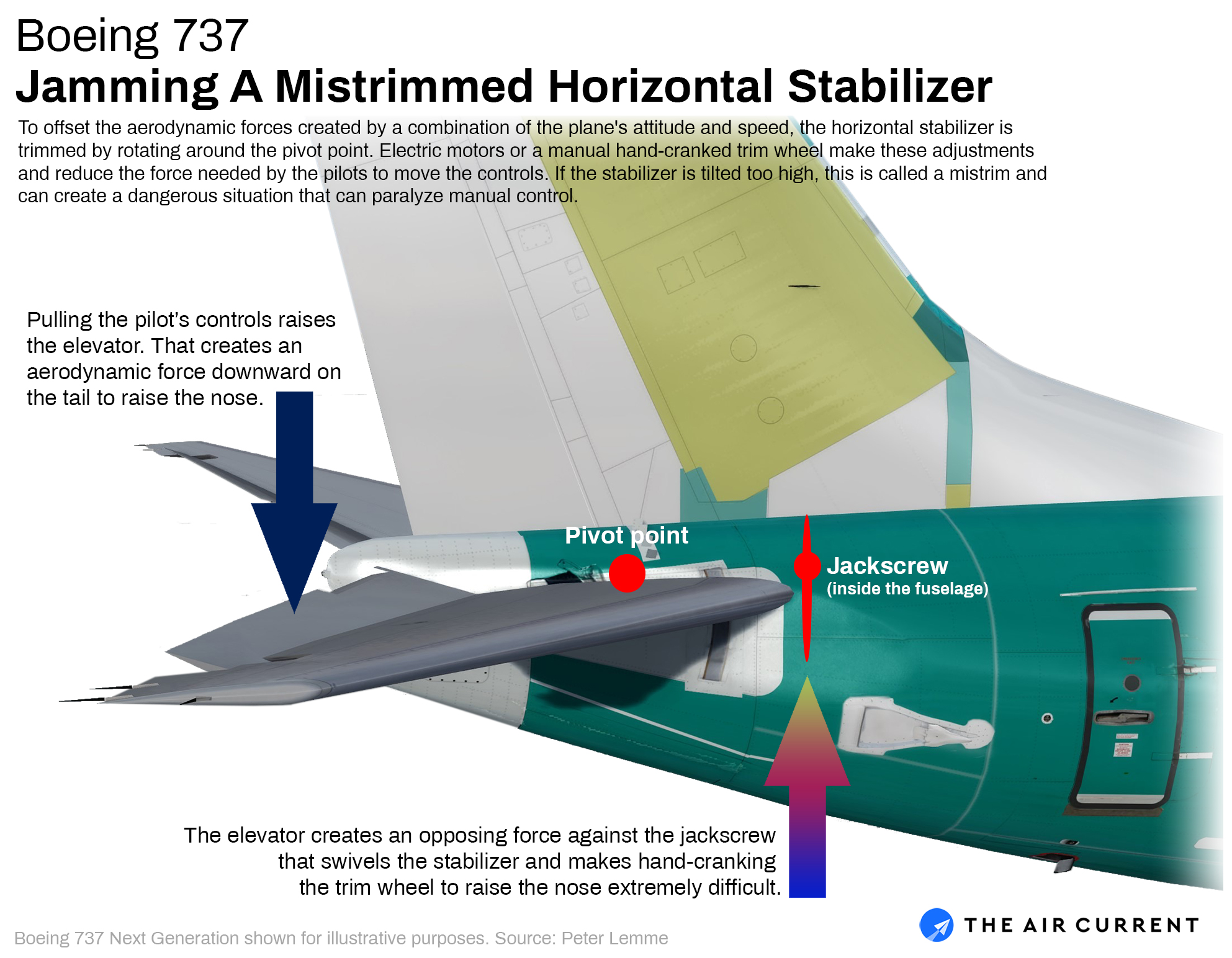

Subscribe to TACThree generations of 737s ago, pilots flying the 737-200 — a slightly longer version of the original 1967 airliner — were trained that if the jet’s horizontal stabilizer tilts too far — pushing the jet’s nose downward — hand cranking the trim wheel won’t work (after flipping the cut-out switches) while at the same time pulling back on the controls, according to Lemme and an Australian pilot who sought anonymity to speak freely about his experience training on the 737-200.

The trim wheel barely budges, but why?

As pilots would pull on the jet’s controls to raise the nose of the aircraft, the aerodynamic forces on the tail’s elevator (trying to raise the nose) would create an opposing force that effectively paralyzes the jackscrew mechanism that moves the stabilizer, explained Lemme, ultimately making it extremely difficult to crank the trim wheel by hand. The condition is amplified as speed — and air flow over the stabilizer — increases.

“I’m very confident [this flight control issue is] going to be looked at closely as part of the many reviews that are ongoing with these accidents,” said Jeff Guzzetti, former director of the Federal Aviation Administration’s Accident Investigation Division. Guzzetti also noted that the high rate of speed and steadily maintained engine thrust are also likely to be considered compounding factors.

The FAA announced Wednesday that it formed a joint technical review with NASA, industry representatives and nine civil aviation authorities to examine the 737 Max’s automated flight control systems and training. The joint review is the latest in a series of inquests and follow U.S. Congressional, the Departments of Transportation and Justice and the twin international investigations into the crash of Flight 302 and Lion Air 610 on October 29, 2018 near Jakarta.

Related: 737 Max grounding threatens to unravel the aviation certification world order

Boeing Commercial Airplanes Chief Executive Kevin McAllister said, “We will carefully review the…preliminary report, and will take any and all additional steps necessary to enhance the safety of our aircraft.” The company is currently developing updates to its training and software to “to ensure unintended MCAS activation will not occur again.”

“It’s our responsibility to eliminate this risk. We own it and we know how to do it,” said Boeing Chief Executive Dennis Muilenburg in a lengthy message posted Thursday.

Unresponsive Manual Trim

Three minutes after first experiencing flight controls issues with the Ethiopian 737 Max, the captain of Flight 302, Yared Getachew, asked his first officer “if the trim is functional,” according to the preliminary report. The first officer “replied that the trim was not working and asked if he could try it manually. The Captain told him to try.” Eight seconds later First Officer Ahmed Nur Mohammed “replied that it is not working.” The report notes that the controls of the jet were pulled to raise the jet’s nose from the moment the MCAS system activates erroneously.

What contribution, if any, the lockup — known as a mistrim — played in the Ethiopian crash is unclear, but the revelation of a long-standing design issue adds a fresh layer of complexity into the investigations and what guidance and training was provided to 737 Max pilots to recover from an erroneous activation of the MCAS system.

Related: Boeing issues 737 Max fleet bulletin on AoA warning after Lion Air crash

Lemme posted his initial summation of the conditions that would create a flight control lockup prior to Tuesday evening’s Wall Street Journal report that revealed the crew had initially followed proper procedures. Lemme deliberately included no mention of the Ethiopian crash. Without supporting facts from the preliminary report, Lemme did not want to imply a link to the on-going Ethiopian investigation. The Air Current was interviewing Lemme about the mistrim issue as that news broke on Tuesday evening.

Separately, Lemme has found himself in the middle of the investigation itself and said that he was served on Monday afternoon with a wide-ranging subpoena from the Department of Justice as part of its criminal inquiry into the 737 Max. Lemme left Boeing 22 years ago and was not involved in any aspect of the development of the 737 Max.

Lemme is not the only one to note the compounded challenge of trying to manually crank the trim wheel while attempting to keep the nose of the aircraft raised. YouTube Channel Mentour Pilot, in conjunction with Leeham News, recreated the same conditions inside a 737 Next Generation simulator. The older generation 737 does not have MCAS — a feature exclusive to the 737 Max — but can simulate a horizontal stabilizer’s runaway trim. The video intended to illustrate how the design issue could compound an already difficult situation, even with all the proper procedures carried out. With the trim pushing the nose down and the controls pulled back by the pilot to maintain altitude, the first officer could barely crank the trim wheel, nearly out of breath while fighting the mechanical system. The video was only posted briefly on Wednesday morning before it was removed.

Detailed guidance on handling this situation isn’t part of the contemporary 737 training manual, however it does makes reference to this condition. “Excessive airloads on the stabilizer may require effort by both pilots to correct the mis-trim. In extreme cases it may be necessary to aerodynamically relieve the airloads to allow manual trimming.”

A Roller Coaster Recovery

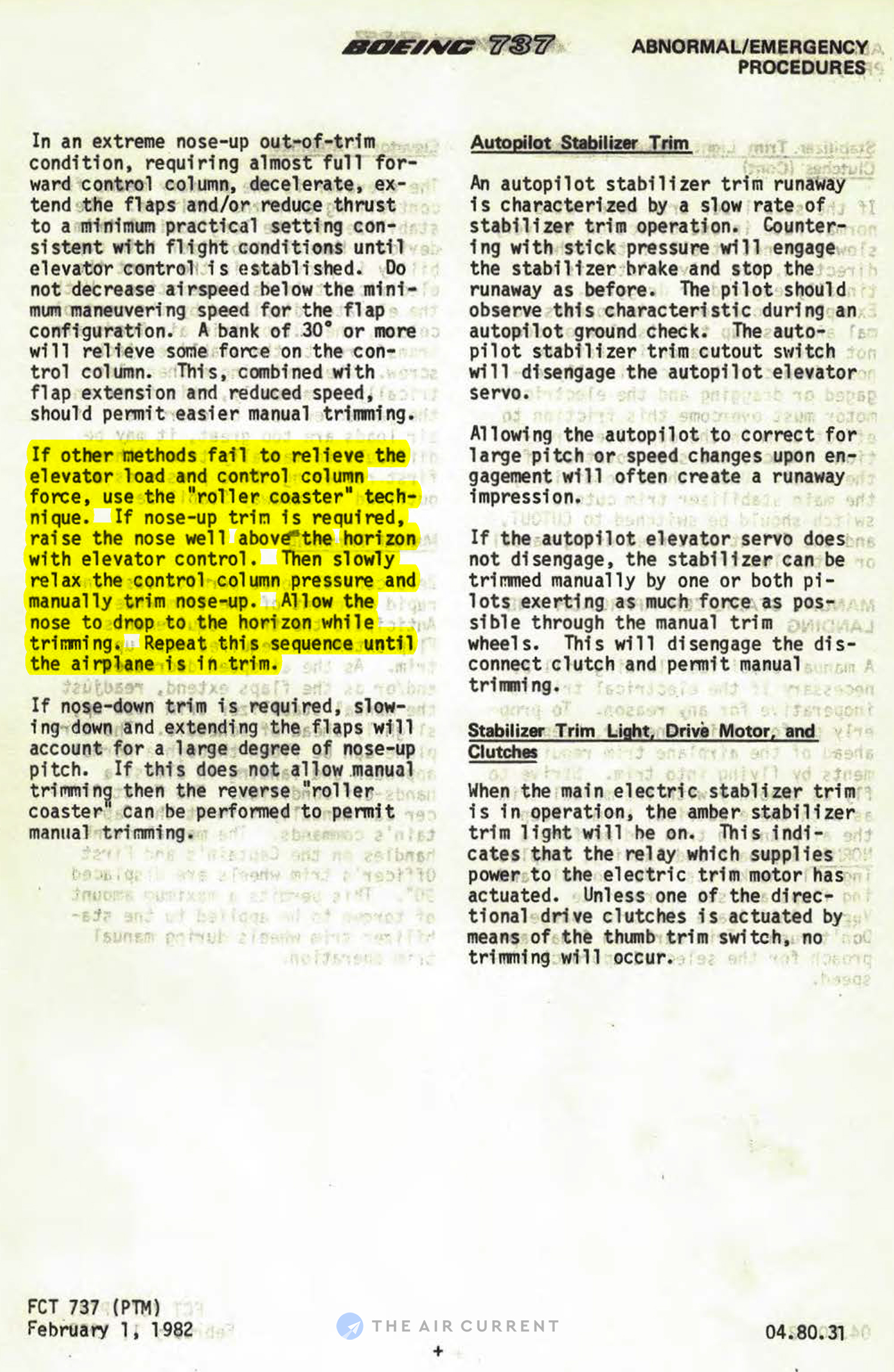

Training materials from the early 1980s model 737-200 spell out the recovery maneuver directly. “If other methods fail to relieve the elevator load and control column force, use the “roller coaster” technique,” according to Boeing procedures dated February 1, 1982 for flying the 737-200. The original documentation was provided to The Air Current by the Australian pilot from his days flying the early-model 737.

“My company practiced the Boeing-stated ‘roller coaster’ techniques during 737-200 simulator training in those days,” said the pilot in an email.

In other words, first relax the controls back to neutral before attempting to crank the trim wheel. Then quickly spin the trim wheel for a few moments, then pull the controls back again. Repeat until the aircraft is stabilized. Think of it like reeling in a fish — it’s incredibly hard to crank the reel handle if you’re pulling back on the rod. You’d relax and lean the rod forward to quickly reel in the next length of line.

In the case of a stabilizer mistrimmed to lower the nose (in an erroneous MCAS activation on the 737 Max), the “roller coaster” is a repeated descending and leveling of the aircraft. The maneuver ultimately relies on having enough altitude to recover and level the aircraft.

The detailed recovery maneuver was not included in the subsequent training documents for the 737 Classics in the mid-1980s, the 737 Next Generation in the 1990s nor most recently with the 737 Max. Additional Boeing documentation dating back to 1975 identified the roller coaster method as the “least desirable” to recover the aircraft during a mistrim situation.

“For some inexplicable reason, Boeing manuals have since deleted what was then — and still is — vital handling information for flight crews,” the Australian pilot wrote on pilot forum PPRUNE.

An earlier version of this article stated that the aerodynamic forces on the tail’s elevator (trying to raise the nose) and horizontal stabilizer (positioned to lower the nose) would combine to paralyze the jackscrew. In fact, the elevator alone would overwhelm the crew’s ability to manually trim the nose upward while struggling to maintain altitude with an improperly configured stabilizer. The graphic and article have been updated to reflect this.

Write to Jon Ostrower at jon@theaircurrent.com.

Subscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention