The National Transportation Safety Board on Tuesday opened a formal investigation into the incident aboard United 1722 on December 18, more than eight weeks after the Boeing 777 suffered a serious upset shortly after departure from Maui.

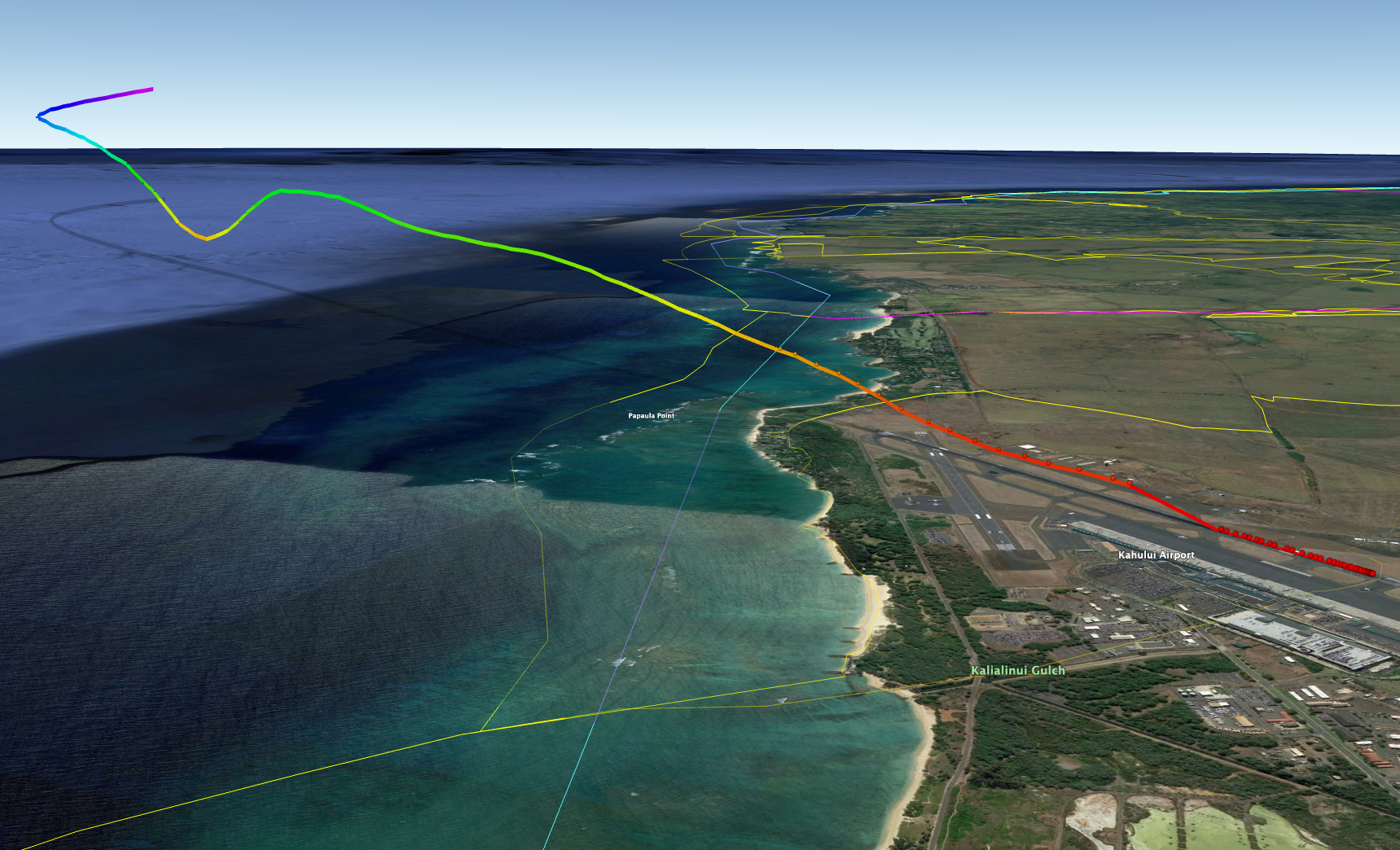

The new inquiry comes two days after The Air Current first reported the incident. The twin-aisle airliner recovered after the brief upset, but not before it reached an altitude of less than 800 feet above the Pacific Ocean and experienced a force 2.7 times gravity during the recovery, according to granular flight tracking data reviewed with Flightradar24 and those familiar with the incident.

Related: United dive after Maui departure adds to list of industry close calls

The inquiries into the incident currently center on how and when the 777’s flaps were retracted and the interaction of the two crew members during the climb out leading to the upset, according to people briefed on the matter.

According to the Maui air traffic control interactions provided by LiveATC.net, a radio call was made to the departure controller by flight 1722 while on a heading of 20 degrees and climbing through 1,400 feet, on its way to an initial altitude of 5,000 feet. ATC then radioed “climb and maintain 16,000” feet. United acknowledged the instruction.

Cross-checked against the granular tracking data, that acknowledgement came 17 seconds before the aircraft’s vertical speed began decreasing as the aircraft crossed 2,000 feet into a layer of overcast clouds in stormy weather.

While the precise sequence of events inside the cockpit around the significant drop in altitude are not currently clear, the timing and progression of retraction of the flaps after takeoff would change the amount of lift the wing generates as it climbs. On its own, that is not enough to produce the type of descent experienced by the aircraft, though how that was then handled by both crew remains a key focus.

The NTSB and FAA did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Flap setting at takeoff is a function of many factors including weather, aircraft weight and runway length, though United pilots tell TAC that a higher flap setting of 15 or 202is typical out of Maui with its shorter 6,998-foot runway. Flap retraction is the responsibility of the pilot monitoring, not the pilot flying the aircraft.

The aircraft reached an altitude of 2,200 feet before it transitioned to a rapid dive, reaching an observed downward vertical speed of 8,600 feet per minute just before the recovery began and the aircraft rapidly climbed back to a stable altitude.

Stephan Schneck, a passenger aboard flight 1722, told TAC that it was clear the aircraft was making an extreme maneuver of some kind, but noted that “visibility was so bad all we could see were clouds and fog so it wasn’t evident how dangerously close to the ocean we were. In the moment I couldn’t have told you if we dropped 200 feet or 2,000 feet.”

The next radio call from ATC came while the aircraft was at around 3,000 feet, clearing the aircraft to a waypoint out in the Pacific. The pilot on the radio sent a standard acknowledgement: “United 1722 heavy, proceed direct EBBER.”

United referred to its earlier statement and declined comment to The Air Current.

United itself has had an ongoing flight safety investigation into the incident since December and the crew members have been receiving additional training following the incident. United and the Federal Aviation Administration said that the crew filed the appropriate internal safety reports after the flight arrived in San Francisco. United said the event did not warrant NTSB notification given the lack of damage to the aircraft or injuries to the passengers or crew.

Also on February 14, on the heels of the announcement from the NTSB, FAA Acting Administrator Billy Nolen sent a memorandum to the FAA Management board with an explicit “Safety Call to Action.”

The blunt message acknowledged the aggregate safety of the U.S. aviation system, but stated, “we cannot take this for granted. Recent events remind us that we must not become complacent. Now is the time to stare into the data and ask hard questions.”

Nolen announced that he is establishing a formal safety review team to “examine the U.S. aerospace system’s structure, culture, processes, systems, and integration of safety efforts.” The FAA in March will hold a Safety Summit with commercial and general aviation leaders, unions and others to “examine which mitigations are working and why others appear to be not as effective as they once were.”

Further, Nolen called for “a fresh look” at safety data being collected by the agency. “We need to mine the data to see whether there are other incidents that resemble ones we have seen in recent weeks. And we need to see if there are indicators of emerging trends so we can focus on resources to address now,” he wrote.

Lastly, Nolen said the review would also focus on the FAA’s Air Traffic Organization to assess “internal processes, systems, and operational integration” and “to explore actions needed to reinforce a collaborative, data-driven safety culture.”

The previously unreported United event was part of a string of recent air safety incidents and operational disruptions that, while they resulted in no damage or loss of life, represented unusually close calls involving the largest U.S. passenger and cargo carriers.

Nolen is slated to testify at a Senate Commerce Committee hearing on Wednesday morning about the recent failure in January of the FAA’s Notice to Air Missions (NOTAM) system that briefly halted departures nationwide.

“We know that our aviation system is changing dramatically,” wrote Nolen. “Now is the time to act.”

Write to Jon Ostrower at jon@theaircurrent.com

Subscribe to TACSubscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention