With a method called program accounting, long blessed by both the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and its auditor, Deloitte, Boeing spreads its high early costs of jetliner production over a roughly 10-year block of deliveries, enabling it to book future earnings in times of steep cash usage. Ultimately the intent is to balance out the enormous costs of producing a jetliner and recognize the long-term rewards of a successful program.

Program accounting is not without significant controversy, drawing the scrutiny of the SEC in 2016, according to the Wall Street Journal. The existence or outcome of that inquiry has never been confirmed by Boeing or the SEC. Yet, critics of the method say there remains far too much uncertainty in its assumptions for Boeing to look a decade into the future and tell investors that it will predictably recover those production costs.

Related: A question of profitability again hangs over Boeing’s 787

Airbus and Bombardier both use different accounting methods, with losses reported on new aircraft programs as they are developed and go into production.

While the method has given Boeing the ability to take advantage of the near-term earnings that come from program accounting, the opposite also remains true once a program begins to generate positive cash with each airplane built as production costs fall and supplier contracts slim down. For example in all of 2018, Boeing reported commercial airplane earnings under program accounting of $7.8 billion, but had it tallied by unit cost, the earnings would’ve been a billion dollars higher.

But how does program accounting work and how is it used by Boeing to calculate profitability? The Air Current explains.

Airplanes are bundled into a block — known as the accounting quantity — the equivalent of reasonably expected run of production over roughly a decade. Inside that block, Boeing is able to average its production costs and revenues to calculate the program’s profitability. The Air Current breaks down the moving, albeit simplified, elements of program accounting.

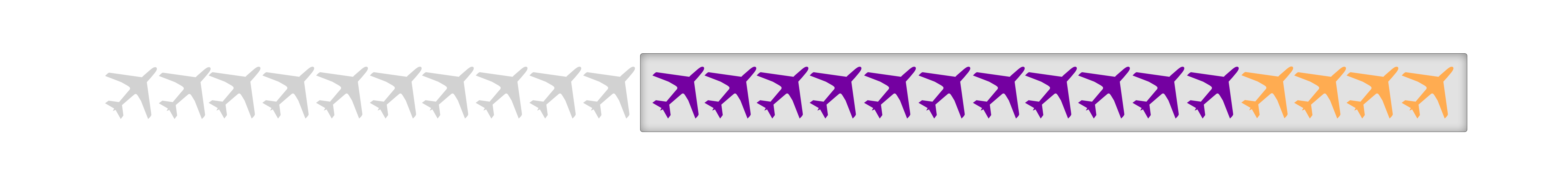

For Boeing’s quarterly disclosures, aircraft in the block are split into three groups. Each airplane in this example represents 20 aircraft. The first airplane off the line is always the most costly, taking the longest to go through the factory as assembly crews learn. Subsequent airplanes are less expensive to produce as the assembly becomes more familiar and processes are mastered and improved as production increases. That also allows production tooling, an overhead cost, to be used more efficiently. Generally speaking, as production increases unit costs will fall.

The first airplane off the line is always the most costly, taking the longest to go through the factory as assembly crews learn. Subsequent airplanes are less expensive to produce as the assembly becomes more familiar and processes are mastered and improved as production increases. That also allows production tooling, an overhead cost, to be used more efficiently. Generally speaking, as production increases unit costs will fall.

In this example, the average cost of each plane in the 500 airplane block is estimated to be $100 million. While the individual cost of each airplane varies, Boeing is able to make this estimate based on knowing its planned productivity improvements, labor contracts, production rate and supplier agreements.

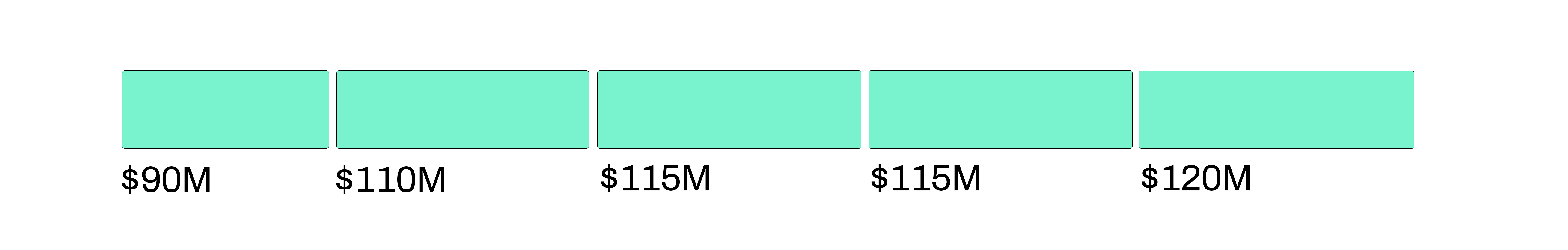

Across those 500 airplanes in the accounting quantity, Boeing knows how much each airplane was sold for and its average sales price, or revenue, is estimated to be $110 million — a profit margin of 10% against the average calculated cost of $100 million.

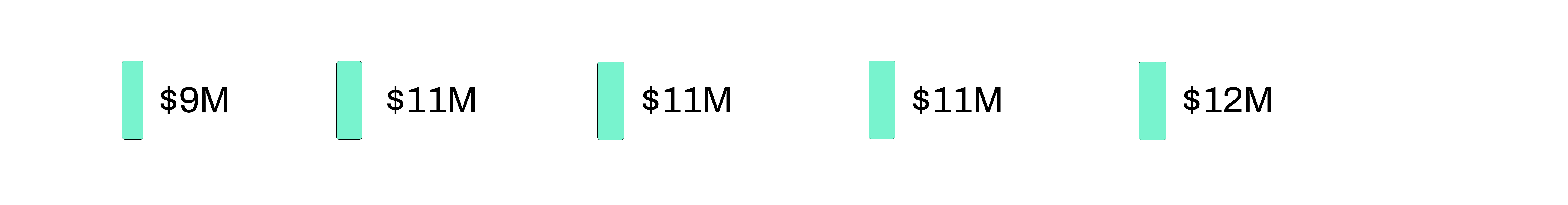

Across those 500 airplanes in the accounting quantity, Boeing knows how much each airplane was sold for and its average sales price, or revenue, is estimated to be $110 million — a profit margin of 10% against the average calculated cost of $100 million.  With its accounting method, that 10% profit margin translates into these program accounting profits, reported in its quarterly earnings.

With its accounting method, that 10% profit margin translates into these program accounting profits, reported in its quarterly earnings. However, the real time cash profits or losses per plane show a very different picture with significant losses early and greater profits later in the program. Boeing reports those costs every quarter.

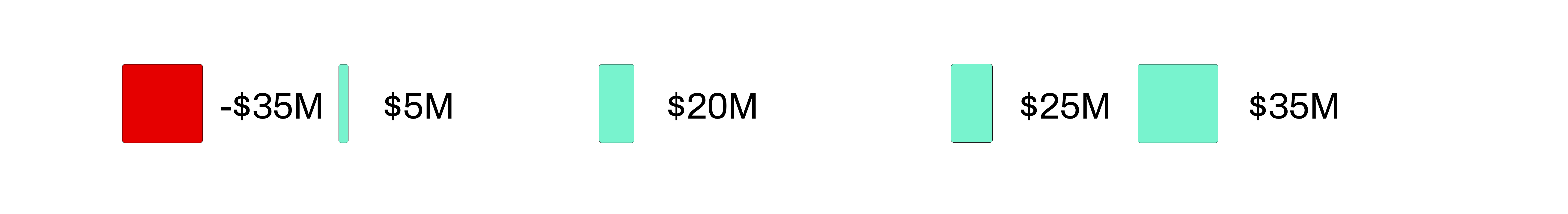

However, the real time cash profits or losses per plane show a very different picture with significant losses early and greater profits later in the program. Boeing reports those costs every quarter. If an aircraft costs is greater or less than the average costs — in this case $100 million — the amount is categorized as a deferred production cost (DPC). Early in the program, those costs grow quickly, but as production becomes more efficient, the cost to make each plane drops below the $100 million average and those deferred costs begin to be recovered on each plane.

If an aircraft costs is greater or less than the average costs — in this case $100 million — the amount is categorized as a deferred production cost (DPC). Early in the program, those costs grow quickly, but as production becomes more efficient, the cost to make each plane drops below the $100 million average and those deferred costs begin to be recovered on each plane. In this example, the DPC peaks at a cumulative $3 billion in cash after delivering the first 200 airplanes, but Boeing’s accounting nets $2 billion in program profits.

In this example, the DPC peaks at a cumulative $3 billion in cash after delivering the first 200 airplanes, but Boeing’s accounting nets $2 billion in program profits.

Based on Boeing’s estimates, all the planes not yet delivered are expected to be sold at a profit sufficient to recover that $3 billion in cumulative deferred production costs and return that original 10% profit margin. With those $3 billion in deferred costs, the remaining 300 airplanes in the accounting quantity would need to be sold at an average profit of around $12 million each.

With those $3 billion in deferred costs, the remaining 300 airplanes in the accounting quantity would need to be sold at an average profit of around $12 million each.

As part of the program accounting process, Boeing includes production of airplanes that have not yet been assigned to an airline. Likewise, some airplane production positions already earmarked for specific airlines are not included in its accounting quantity because delivery is so far out Boeing can’t reasonably estimate today how much they will cost to produce each one.

Write to Jon Ostrower at jon@theaircurrent.com

Subscribe to Continue Reading

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention