Log-in here if you’re already a subscriber

Air safety reporting by The Air Current is provided without a subscription as a public service. Please subscribe to gain full access to all our scoops, in-depth reporting and analyses.

Nearing the end of its routine flight from the midwest, a regional jet prepared to land on Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport’s (DCA) Runway 1 when an air traffic controller instructed the pilots to instead change to Runway 33 — a “circling” procedure sometimes used during congested periods at the airport.

At the same time, a military helicopter was transiting DCA’s airspace using a helicopter route along the Potomac River that crossed the approach path for Runway 33. Over a radio frequency used exclusively by helicopters to communicate with air traffic control, the pilot was instructed to maintain visual separation: keep the jet in sight and maneuver to stay well clear of it.

As the jet descended on approach, the distance between the two aircraft — now at the exact same altitude — narrowed to less than a thousand feet. The controller asked the helicopter multiple times to confirm it had the nearby traffic in sight and then instructed the helicopter to “pass behind” the regional jet.

Moments later, the airliner aborted its landing, narrowly avoiding a collision. The DCA tower controller, while attempting to deconflict the two aircraft, had accidentally turned the helicopter in the wrong direction.

It was May 24, 2013. Both aircraft landed safely.

More than a decade later, a nearly identical scenario in the exact same location would result in the deaths of 67 people. On Jan. 29, 2025, an American Eagle CRJ700 operating as PSA Airlines Flight 5342 was circling for the same runway when it collided with a U.S. Army 12th Aviation Battalion UH-60L Black Hawk conducting a night vision goggle evaluation flight on the same helicopter route over the icy waters of the Potomac.

Many of the issues that created the circumstances for the close call in 2013 — including fundamentally flawed airspace that left the controller with a razor-thin margin for error — persisted on the night of Jan. 29. That earlier close call was not caused by a singular human act, and neither was the crash that became the first major U.S. commercial air safety disaster in 16 years.

Rather, it was the predictable outcome of a deteriorating system that had been flashing warning signs for years. After the fatal crash on Jan. 29, the United States National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) identified over 15,000 instances between October 2021 and December 2024 alone in which helicopters and commercial airplanes came dangerously close to each other in the skies above DCA — key Federal Aviation Administration safety data that wasn’t shared or acted on.

The Air Current reviewed thousands of pages of NTSB investigative materials in addition to 30 hours of proceedings held by the Board in August outlining the facts of the accident. TAC also interviewed dozens of government and military officials, airline leaders and safety experts for deeper insights into the circumstances surrounding it.

Though the NTSB has yet to issue its final report on the crash, the evidence shows the accident was a tragic failure not only of the protections intended to keep the traveling public and users of the national airspace system (NAS) safe, but also of the institutions that design and maintain them.

A fundamentally flawed airspace design

The 2013 near-miss was a catalyzing event for DCA controllers and staff. DCA’s then chief controllers’ union representative told the NTSB earlier this year, “in my tenure the five years prior I don’t recall ever seeing anything that close.” Controllers mobilized as a result, seeking to change some of the airspace structure to remedy what they saw as a serious safety issue.

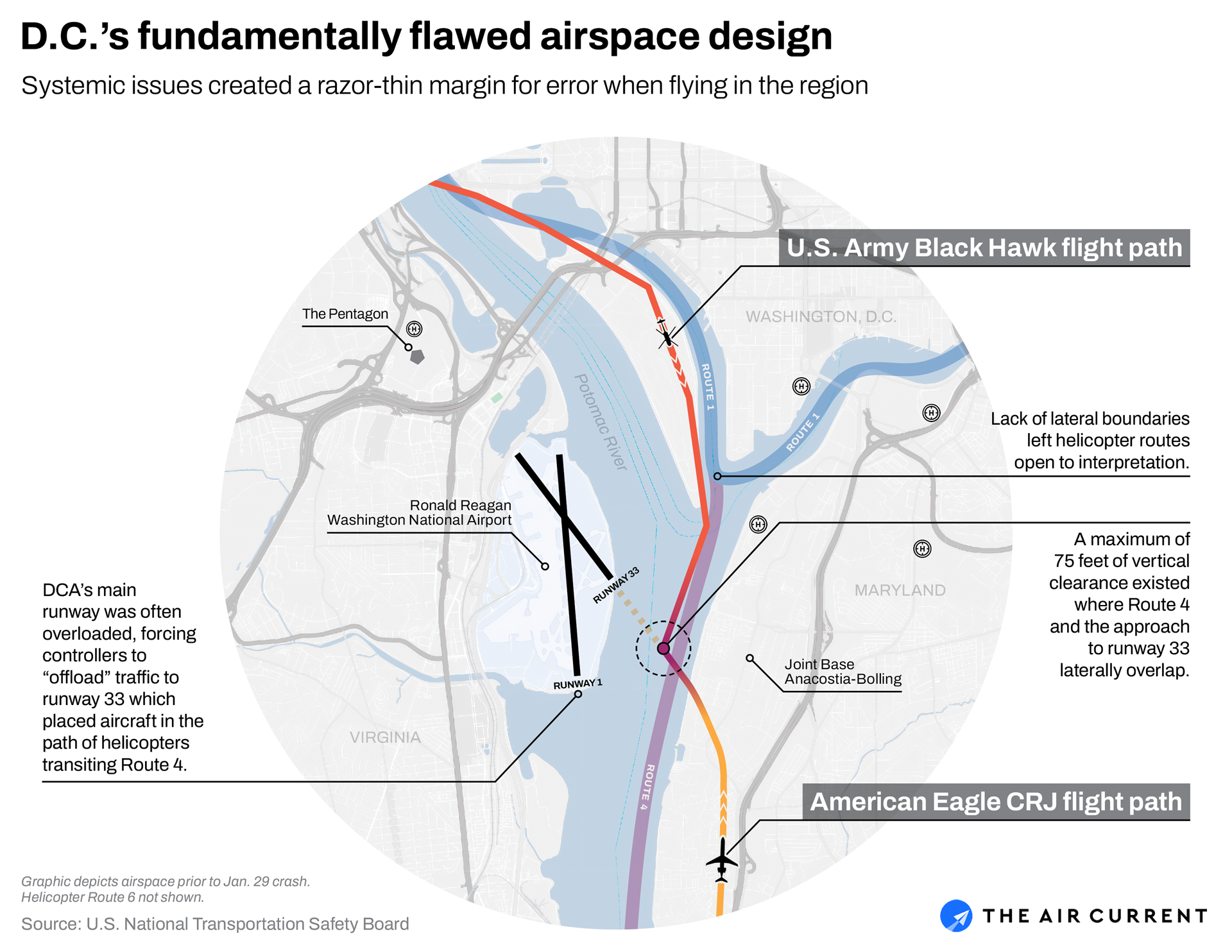

DCA’s Runway 1 is the single busiest runway in the United States, according to the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority which runs Reagan National. The relatively small region of airspace around it is packed with high amounts of commercial traffic along with military fixed-wing and rotorcraft operations, medical transport flights and police aircraft. Several of the 23 D.C.-area helicopter routes are threaded between DCA’s fixed-wing pathways, allowing rotorcraft to rapidly transit the airspace rather than go around it.

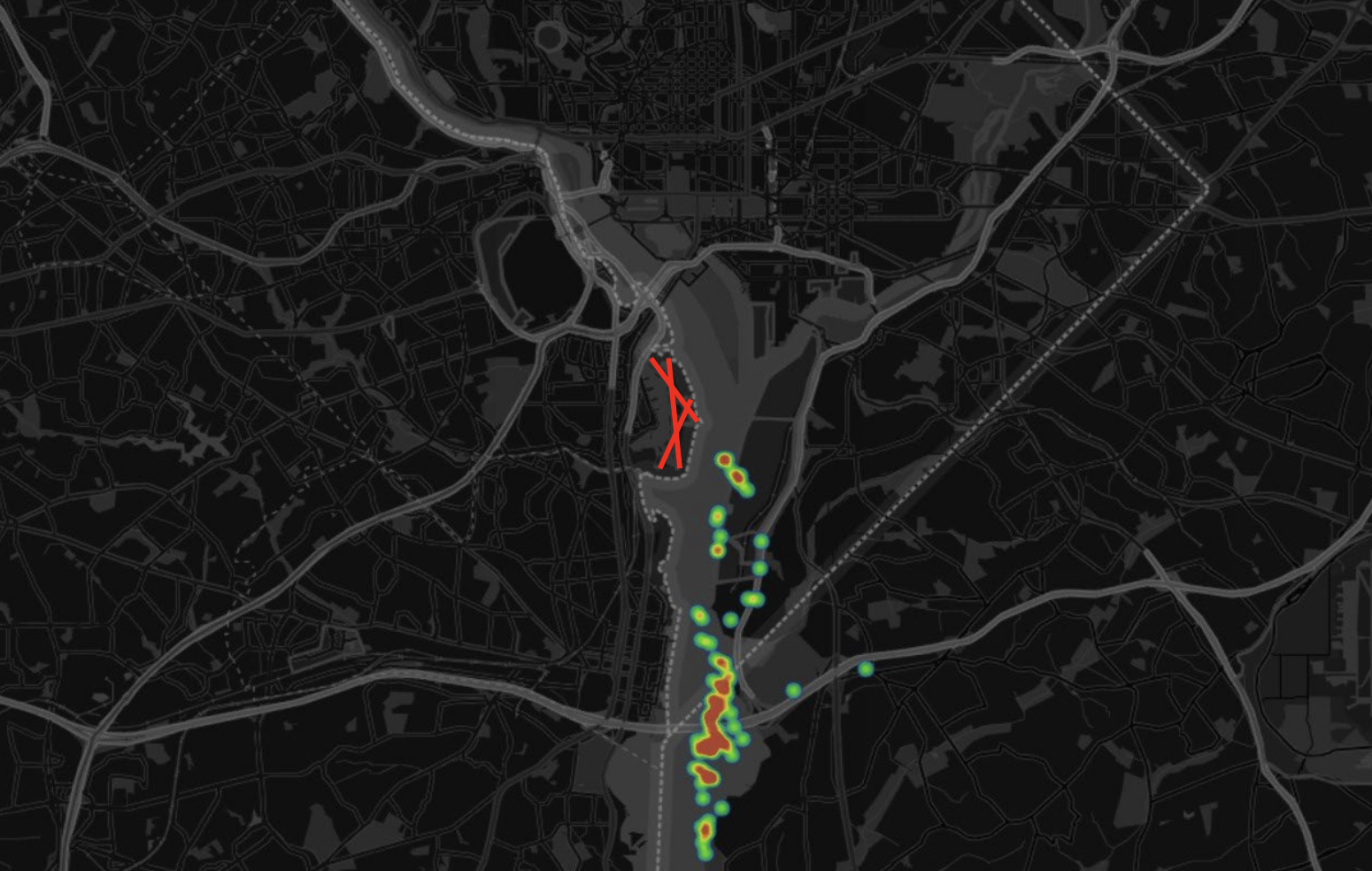

The route flown by the helicopters in both the 2013 near-miss and the 2025 crash was Route 4. Up until the January crash, the route ran from Hains Point just northeast of DCA along the east bank of the Potomac River and over the Wilson Bridge to Fort Washington, Maryland. Where the route passes by DCA, pilots were instructed to fly at or below 200 feet above sea level.

After the 2013 near-miss, NTSB records show that DCA tower controllers proposed moving this segment of the route further east, over highway 295, to deconflict helicopters with traffic landing on Runways 1 and 33 at DCA. The former DCA union representative said controllers were “told no” by FAA management. The proposal resurfaced a few times over the years but was never acted on. Clark Allen, the DCA tower operations manager at the time of the crash, said during the NTSB’s August investigative hearing that it was never implemented because the military relied on the helicopter routes for national security reasons.

After being rebuffed, controllers in 2022 instead proposed adding warnings on the Baltimore-Washington helicopter navigation charts about potential conflict zones between rotorcraft and fixed-wing traffic — including one in the exact spot the 2025 crash happened.

“Our thought process with [the hot spots] was if we can’t change these routes or move them or delete them, then we need to, at the bare minimum, draw attention to it and the safety issue we find with it,” Allen told the NTSB in a post-crash interview. He said the hotspot proposal was denied because the FAA charting office had no national standard for depicting such warnings on visual flight rules (VFR) charts.

This lack of action left the routes and the risk of a collision unchanged on the evening of Jan. 29. Multiple Army pilots — including senior officers — as well as air traffic controllers interviewed by investigators said they either did not know or assumed that the routes procedurally separated traffic, meaning if every aircraft was where it was supposed to be, no conflict would occur.

“Maybe I just have too much trust in … this thing that’s printed in front of me, because I generally think that this is going to keep us safe,” said a pilot from the 12th Aviation Battalion’s Bravo Company, the same Army flight company as the accident crew. The pilot was speaking to NTSB investigators about the Baltimore-Washington area helicopter route chart shortly after the crash.

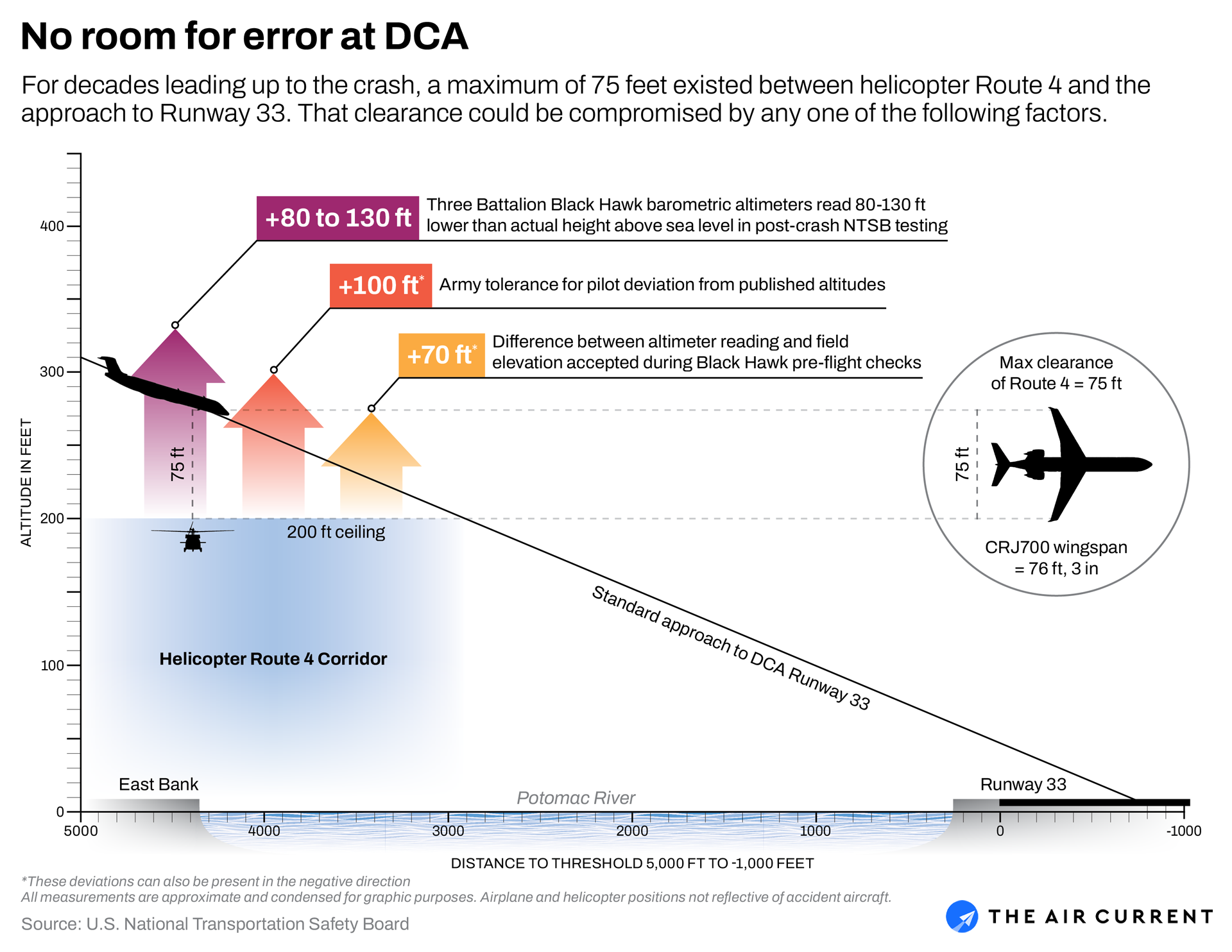

The Board revealed in its March preliminary report that even under the best circumstances with both aircraft exactly where they should be, the point where Route 4 and the approach path to Runway 33 laterally overlap left a maximum of 75 feet of vertical clearance — approximately the wingspan of a CRJ700. That vertical clearance decreases the closer a helicopter gets to the center of the Potomac River and therefore to the approach path of Runway 33.

Even with charts in hand, just where a pilot should be at any given time was ambiguous at best. Helicopter routes, like all VFR routes in the NAS, have no defined lateral boundaries, meaning exactly how and where to fly the procedure was up for interpretation. Katie Murphy, who manages an FAA team responsible for creating VFR charts, described these routes as “recommended paths” during the investigative hearing, meaning pilots had just a vague drawing and a two-sentence explanation on the side of the helicopter chart instructing them how to fly a complex procedure in busy airspace. One Army aviator told the NTSB they were briefed to stay within half a kilometer on either side of the route.

Aaron Smith, Maryland Prince George’s County Police Department’s head of aviation and a former Army aviator told investigators, “Flying in the D.C. area, there is so much information that is not written. It’s not on the chart.”

“For instance, nowhere on the chart does it say that D.C.’s rush hour in the evening runs from 4 p.m. to about 9 p.m. and Sunday is really bad,” he said in a post-crash interview. “It’s stuff from flying in the region that you know.”

The FAA told TAC earlier this year it is evaluating whether to add lateral boundaries to helicopter routes but an agency spokesperson did not say if it has done so yet in a statement provided to TAC for this story. Even with lateral boundaries, visual routes rely on pilots’ eyeball navigation and avoidance of obstacles and are therefore inherently approximate. To actually guarantee traffic separation and obstacle clearance would require carefully designed, low-level instrument routes which require users to have expensive, more precise navigation equipment and for pilots to adhere closely to prescribed procedures.

There were other discrepancies in how these routes were flown, too. Investigators conducted tests with three Lima model Black Hawks from the Army’s 12th Aviation Battalion — the same model as the accident helicopter — and found that the barometric altimeters pilots used to maintain altitude were consistently showing 80 to 130 feet lower than their actual height above sea level. The NTSB’s testing report said these errors were “similar” to those seen on the accident aircraft, suggesting the accident pilots may have been higher than they thought they were.

The Baltimore-Washington area helicopter route chart instructs rotorcraft to “maintain the maximum altitude charted” on a given route unless weather doesn’t allow or air traffic control instructs otherwise, though FAA officials said at the NTSB hearing these were simply “suggested” altitudes for pilots. That variability implies some excursions are almost guaranteed, perhaps due to wind gusts or the pilot maneuvering around clouds or obstacles.

On the helicopter route segment where both the 2013 close call and the 2025 crash occurred, FAA data shows nearly 18% of all helicopters were flying at altitudes above the 200-foot limit. And in the year prior to the 2025 accident, about 80% of all helicopter flights within five nautical miles of DCA airport were flown by military operators, according to the FAA data.

The segment between Hains Point and the Wilson Bridge has since been removed as the FAA works to make permanent safety changes to the airspace around DCA, the agency spokesperson told TAC via email. The FAA has also eliminated the use of visual separation within five miles of DCA, banned mixed helicopter and fixed-wing traffic around the airport and modified the helicopter route chart.

“Safety is and will always be the FAA’s top priority,” the spokesperson said. “Our mission is to protect pilots, flight attendants, crews, and the traveling public. That requires identifying risks early, confronting them transparently, and taking decisive action to keep the National Airspace System safe … We are not operating the way the old FAA did. Today, we are acting proactively to mitigate risks before they affect the traveling public.”

Capacity concerns falling on deaf ears

Meanwhile, warnings had persisted for years that DCA’s arrival rate was too high. Air traffic controllers both in the tower and at the facility that controls arrivals and departures at the airport, known as the Potomac Terminal Radar Approach Control (TRACON), said the high arrival rate hampered their ability to safely separate aircraft and resulted in backed-up ground traffic on the airport’s minimal taxiway space.

Controllers told NTSB investigators this high rate created the need to offload traffic to the shorter Runway 33, for which the circling maneuver is almost always used to line up aircraft on final approach. This was the exact scenario on the night of the accident — a busy arrival stream for Runway 1 which prompted the controller to ask the CRJ if it was able to change to Runway 33, putting it on course for a collision with the Black Hawk.

In May 2023, a proposal was made by the Potomac TRACON to permanently reduce the rate by about four aircraft an hour, depending on weather conditions. A memo provided to the NTSB advocating for the reduction noted the accelerating post-pandemic trend of airlines upgauging to larger aircraft and the simultaneous phase-out of turboprops and smaller regional jets. This changing fleet mix prohibited most aircraft at DCA — besides some regional jets like the CRJ — from using the almost 2,000-foot-shorter Runway 33 at all, forcing more traffic to the already-congested Runway 1.

That proposal was snuffed for what Allen, the DCA tower operations manager, described as “political” reasons; he claimed it was never elevated to the proper management level for consideration.

Some controllers said in NTSB interviews that they felt the high demand from airlines and lawmakers to operate more flights at D.C.’s most convenient airport made it harder to convince leadership to reduce the rate. That influence was often routed through FAA management or the national air traffic control system command center in Warrenton, Virginia. Reagan Airport is one of a handful of U.S. airports whose coveted “slots,” or scheduled authorizations to take off and land, are regulated by federal law. Regulations allow a maximum of 60 scheduled slots per calendar hour (e.g. 8 p.m. to 9 p.m.) at DCA, not based on a rolling 60-minute period.

Potomac TRACON air traffic manager Bryan Lehman told investigators that airlines — specifically American Airlines, the largest user of the airport and parent of PSA Airlines — would abuse this rule by scheduling more departures and arrivals in the second half of one calendar hour and into the first half of the subsequent hour, overloading the airport. Issues with this policy were echoed by multiple other controllers interviewed.

“No one will stop them,” Lehman said in a post-accident NTSB interview. “So I don’t know how American has this much pull … but it’s a wink, wink, that people know what’s going on.”

“Safety is always the top priority in everything we do, including the scheduling and execution of our operation,” an American Airlines spokesperson told TAC in an emailed statement. “The FAA determines how many aircraft operate at any given airport. At DCA, it sets rules that establish the number of operations allowed, the number of operations allowed per hour, and the methods for reporting operations and complying with all operational restrictions. Our scheduling practices comply with all regulations.”

“This is not a relationship of equals: FAA is the regulator and we, and other airlines, are the regulated entity. We don’t have the wherewithal to pressure the FAA and furthermore, we would never make a decision or pressure anyone to make a decision that could have any degradation to safety,” the spokesperson elaborated in a separate statement, pointing out that no controllers specifically said during the NTSB hearing they felt direct pressure from operators.

The FAA spokesperson said that it has “encouraged carriers to distribute flights more evenly across each hour to prevent unnecessary strain on the system.”

Around the same time as the 2023 rate reduction proposal, Congress was drafting the FAA’s next five-year reauthorization bill. Many lawmakers wanted more direct flights to and from their own districts and, supported by a multimillion-dollar campaign backed by major airlines, proposed to add five more departure and arrival slot pairs per day to DCA in that legislation.

The airport opposed the plan, as did the FAA, which called any assertion by Congress that the airport could accommodate more flights “flawed,” according to a May 2023 FAA memo included in the NTSB’s docket. A separate memo written by Lehman around the same time, also published in the docket, warned adding flights would “exacerbate current operational challenges.” The law was overwhelmingly passed by both chambers of Congress about a year later.

Prior to the 2025 crash, the airport’s maximum arrival rate was 36 per hour when Runway 1 was in use, a figure that was temporarily lowered to 26, and then slowly raised to 30 in the weeks following the crash, the FAA told TAC. As of publication, that 30 rate is still in effect, but has not been formalized as the permanent, baseline rate. TAC understands that efforts to permanently lower the rate to the level of the temporary reduction have largely stalled.

A uniquely challenging mission

While pilots generally described the safety culture of the 12th Aviation Battalion as strong, the unit faced uniquely challenging mission requirements and operational constraints. Rather than a regular deployment schedule, the battalion is instead always on alert, required to respond within 15 minutes to “continuity of government”4 or VIP transport missions.

Chief Warrant Officer 5 David Van Vechten, former brigade standardization officer, said Bravo Company specifically was in “the hurt locker” from a morale perspective as the mission cadence compounded with “the aging fleet of UH-60s” that would often break down. “You sit around all day, and then you go home,” he said. “Morale goes down when aircraft [start] breaking because now you’re not flying, and everybody wants to be in the air flying.”

The impact of frequent maintenance issues is particularly acute for the battalion, as the on-call mission requires about 60% of its aircraft and crews to be on standby at any given time, Army officials told the NTSB. While being on standby doesn’t necessarily prevent a crew member from receiving training — or an aircraft from being used for training — a higher cadence of maintenance issues meant it was challenging to make resources available for training while meeting the mission requirement.

“Day-to-day maintaining proficiency and readiness is extremely challenging within 12th Aviation Battalion because simultaneously, they are standing by to support their NORTHCOM (U.S. Northern Command) directed mission,” The Army Aviation Brigade (TAAB) Commander Colonel Andrew DeForest said in an interview with NTSB, adding that this setup made scheduling maintenance more challenging since aircraft were in high demand. “Very thin margin, in my opinion.”

All of the crew members involved in the January crash were properly rated and current to fly the Black Hawk per U.S. Army and FAA experience minimums. Yet battalion personnel raised questions to investigators as to whether those minimums ensured proficiency for crew members.

The 12th Aviation Battalion’s UH-60 pilots must adhere to Army Flight Activity Category (FAC) 2 proficiency minimums for that aircraft, which require crews to fly 30 hours total every six months, including nine hours of night vision goggle (NVG) time. Within three years of leaving flight school, all new pilots are required to adhere to the higher FAC1 minimums of 48 hours per six-month period and the same nine hours of NVG time.

Captain Rebecca Lobach, who was flying the helicopter at the time of impact and being evaluated on her NVG flying skills that evening, had completed that three-year stretch in July and was subsequently assigned the newer, lower level FAC 2 minimums.

“The minimum hours that aviators must fly in the Army is not enough in my opinion to maintain proficiency,” especially for younger aviators, said Brad Haase, a retired Bravo Company standardization instructor pilot. NTSB personnel records showed that Lobach had accumulated just five flight hours in the preceding 60 days.

Haase added that he believed the Army’s overall Black Hawk training program also made assimilating into the battalion harder for newer pilots assigned to the Lima model, given that initial Black Hawk pilot training at Fort Rucker, Alabama was done on the newer Mike model helicopter. Those helicopters have larger glass avionics displays, better radios and a coupled autopilot for controlling the aircraft in level flight.

Before Army pilots even fly the Black Hawk or their other assigned helicopter platform, they complete primary rotorcraft training on the Airbus UH-72 Lakota, an advanced twin-engine helicopter with augmented flight controls and assistive technologies that make flying easier. In recent years, the Army has admitted that the more technologically advanced aircraft may be degrading basic “stick-and-rudder” skills — so much so that the branch is considering moving away from the Lakota in favor of a simpler platform.

About a decade ago, the 12th Aviation Battalion began taking on more “first-term” aviators right out of flight school, as is the case with most other Army units. This departure from its historically more experienced pilot roster made the group’s highly specialized mission more challenging, the battalion commander said in a post-crash interview with the NTSB. Around a year prior to the 2025 crash, the commander told the Army’s human resources arm that her organization needed “to get the right population of people here to support these missions and what it is that we are asking them to do.”

Their request ultimately resulted in the assignment of fewer first-term aviators, but over that decade-long period many pilots were still sent to the battalion right from basic flight training, including Lobach. (As of February 2025, 11 out of 102 of the battalion’s aviators had come straight from flight school, according to NTSB interviews.)

Haase said he considered pilots who trained exclusively on the Mike model “brand-new pilots” when assigned to a unit that used the Lima model, the specific type of Black Hawk helicopter involved in the DCA crash. When transitioning back to older aircraft, pilots had to readjust to traditional steam gauges and what instructor pilots described as a complex collective trim system which can cause inadvertent altitude changes to happen quickly.

Van Vechten, the former brigade standardization officer, said “the instruments are difficult to see, and it literally takes a heartbeat to be 100 feet off on altitude in a Lima … especially over water [while wearing] goggles” — a shortcoming that may have been compounded by the gusty wind conditions on the night of Jan. 29.

One Bravo Company pilot who had flown with Lobach the week prior said she appeared “rusty” on the controls but there was “nothing that stood out” about her flying. Van Vechten recalled specifically working with her as a student on how to properly manage the trim system in flight.

At one point on the night of the accident, the Black Hawk — then controlled by Lobach — climbed to what the instructor thought was 300 feet MSL, about 100 feet higher than the crew should have been. A correction back to what they thought was 200 feet was made promptly afterwards. During the NTSB investigative hearing, Van Vechten said that “within plus or minus 100 feet” of whatever altitude the crew intended to be at amounts to acceptable Army training tolerances.

Most commercial and military helicopters, including the Black Hawk, have two instruments that provide pilots with altitude information — a barometric altimeter, which reads pressure differences to show a corrected height above mean sea level (MSL), and a radar altimeter that shows the height above whatever terrain is directly below the aircraft.

A radar altimeter is equivalent to MSL only when the aircraft is over a flat surface at sea level, which would have essentially been the case for unobstructed sections of the Potomac River. Interview transcripts and hearing testimony indicated that helicopter pilots vary in their procedures for cross-checking the barometric altimeter against the radar altimeter or emphasizing one over the other. Cockpit voice recorder data from the accident flight did not include any mention of the radar altimeter specifically.

Analysis of the cockpit data and voice recorders show that following the correction and until the time of impact, the Black Hawk — now heading directly towards the path of the CRJ on final approach to Runway 33 — was well above the maximum route altitude of 200 feet, showing about 270 feet radar altitude at the time of impact. The NTSB said it has been unable to determine what altitude the accident helicopter crew was seeing on both barometric altimeters, though cockpit voice recorder exchanges suggest they believed they were at 200 feet above sea level at the time of impact.

A disagreement between altimeters is just one potential altitude discrepancy at play. In addition to the defects found by the NTSB in barometric altimeters onboard other battalion Lima model Black Hawks, when checking a barometric altimeter prior to flight, both the FAA and the Army consider the instrument to be airworthy with up to a 70-foot difference from field elevation.

The NTSB has not yet reached a definitive conclusion on what may have caused the 80-130 foot discrepancy, but the aviation industry has understood for decades that barometric altimeters are subject to a slew of inherent limitations. They use decades-old technology subject to fluctuations in outside air temperature and rely on fuselage-mounted air intake tubes for pressure information which can be impacted by the aerodynamic design of the aircraft (known as position and instrument errors).

The Lima model Black Hawk barometric altimeter had a known, “nominal” instrument and position error of about 50 feet in forward flight when equipped with external fuel tanks, as the accident helicopter was, Dan Cooper, senior technical fellow at Black Hawk manufacturer Sikorsky said during the August NTSB investigative hearing. These types of errors — which were also present on the Alpha model Black Hawk first commissioned by the Army in 1979 — were not included in the Army flight manual used by pilots despite a Sikorsky engineering report recommending otherwise, Cooper said.

“You’ve got to put the size of that error in context,” Steven Braddom, acting chief airworthiness officer for the Army’s Combat Capabilities Development Command, said at the hearing when asked why the error had not been included in the flight manual. “We’re talking about something that is 15 to 20 feet above the [specification]. In my experience, typical aircraft separation distances are 500 feet or more.”

Visual illusions

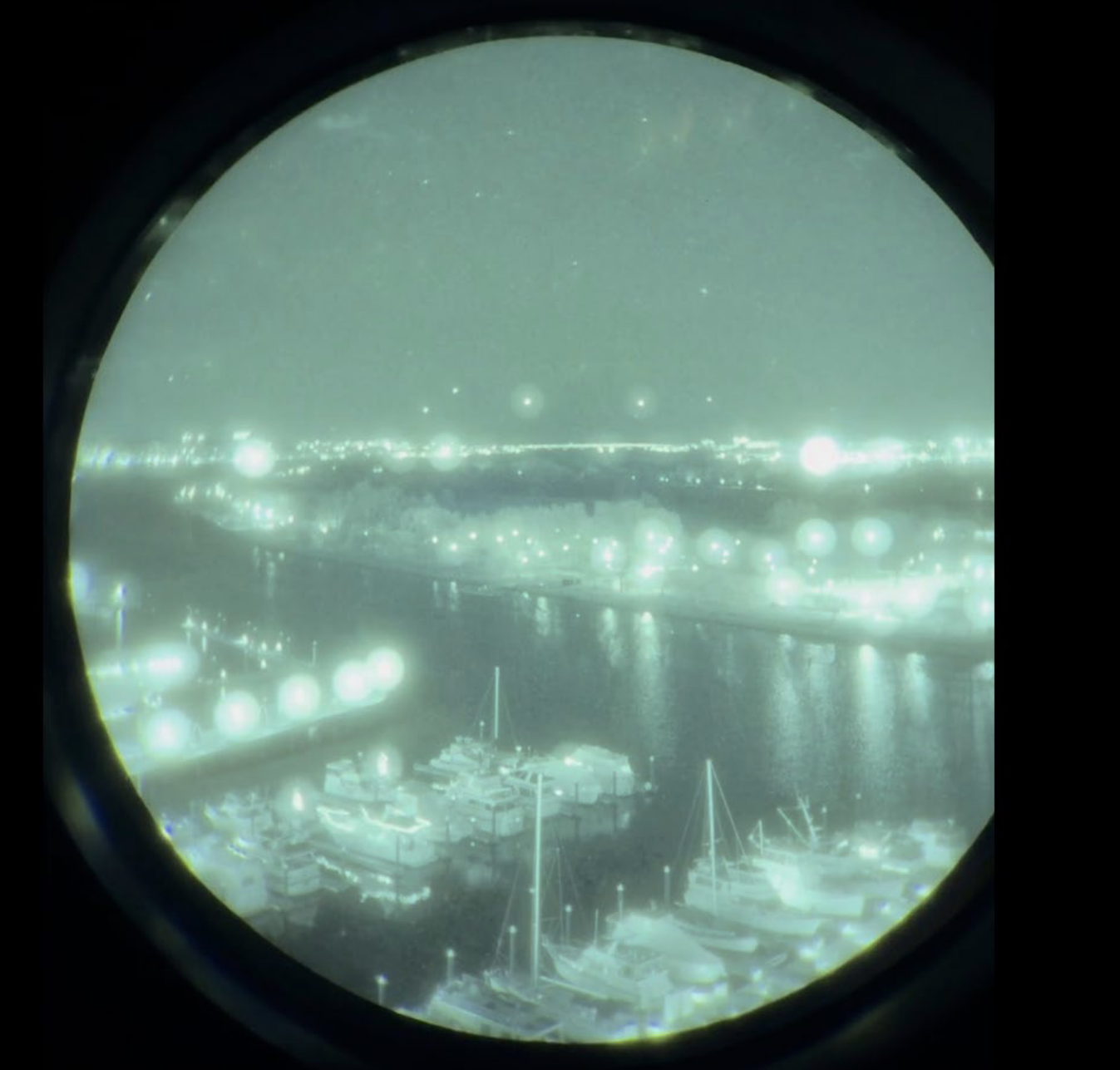

On the evening of Jan. 29, the accident crew was conducting what Army pilots described as a routine evaluation of Lobach’s ability to fly using NVGs, though many told investigators it was challenging to use them in a congested area with considerable city lighting.

NVGs are optoelectronic devices that use image intensification to amplify ambient visible light and convert near-infrared light, allowing a user to see in dark environments. Doing so in high-light environments, such as the airspace around the nation’s capital, can overwhelm the goggles with photons and drown out the picture. NVGs can also impede depth perception and reduce the sharpness of the image seen by the user. Army standardization instructors and other D.C.-area helicopter pilots said crews would often go “unaided” by flipping their goggles up to verify the location of potential traffic.

“I can’t stress enough how much you have to confirm with your naked eye” to properly identify light sources, Van Vechten said. Yet despite the clear benefits of going unaided, the Army never created a procedure which required crews to do so through that part of D.C.’s airspace. Other operators, such as the U.S. Coast Guard’s National Capitol Region Air Defense Facility based at DCA, told investigators they prefer to not use NVGs through this section of airspace. There was no indication on the helicopter’s cockpit voice recorder that the accident crew went unaided to search for traffic.

When flying with NVGs, crews generally utilized visual separation — the practice of seeing and avoiding traffic purely by visual means — to remain separated from other aircraft. Typically, the pilot of an aircraft is asked by an air traffic controller to maintain visual separation after confirming that they have other nearby aircraft in sight. Under this practice, there is no strict lateral or vertical separation requirement and pilots assume the primary responsibility of keeping their distance from traffic.

On the night of the accident, the Black Hawk had executed “pilot-applied” visual separation, in which the crew — not the controller — proactively asks to be approved for the procedure once a controller points out traffic. This practice is not commonly used beyond the D.C. airspace, but Army pilots told the NTSB it helped them reduce radio chatter because they expected controllers to instruct them to maintain visual separation in the next communication anyways.

The controller asked the accident Black Hawk pilots multiple times if they had the CRJ on approach for Runway 33 in their sights, which the crew confirmed. Just seconds before impact, the controller instructed the Black Hawk to “pass behind” the CRJ, a transmission investigators believe the crew did not hear because of a radio interruption by another aircraft.

When Runway 33 is in use, the commander of Bravo company said crews would use visual separation to deconflict with landing airliner traffic about 75% of the time; crews would otherwise be told by ATC to hold near certain visual landmarks until the conflicting traffic had crossed. Other pilots indicated they never transited the area when traffic was landing on 33 and were always asked to hold. One Army pilot told the NTSB visual separation was used “100% of the time.”

The inconsistency about how helicopters were handled in the airspace can be traced back to the DCA tower, where there was no standard procedure for how to deconflict helicopter and fixed-wing traffic. Landmarks on both the north and south side of Route 4 were known by controllers and helicopter pilots as places aircraft could be held, but controllers were never told to always hold that traffic. Rather, they were given many tools to make the decision on their own based on the operation at the time.

Several higher-ranking Army standardization pilots and commanders told the NTSB that aviators sometimes felt operational pressure given the criticality of their mission. “There’s 30 different [landing zones] around the DCA area and we have so many customers that we have to operate for, and the mentality is to get the mission done,” the battalion’s Charlie Company standardization officer said.

Multiple senior officers said they had personally told controllers they had traffic in sight and subsequently requested visual separation approval despite not seeing the aircraft at all, operating under the assumption they would see the target seconds later. No one suggested this practice was explicitly taught to students, but Van Vechten, who told investigators he had done this, said he “can’t be the only one.”

The Bravo Company commander said by not reporting traffic a pilot could “impede” the route of flight if a controller decides the aircraft needs to hold or be turned away to make room for another aircraft it can’t see. Other pilots said that being asked to hold would rarely add more than one to two minutes to a flight.

A spokesperson for the U.S. Army, a party to the ongoing NTSB investigation, did not answer specific questions for this story, instead referring TAC to the Board’s public investigative docket.

“The Army understands and respects the need for families to receive more information regarding the tragic DCA crash,” the spokesperson said. “We acknowledge that many individuals are still seeking answers about the incident and the measures being taken to prevent a similar tragedy … Once the NTSB completes its work and legal proceedings are complete, the Army looks forward to sharing updates about the changes implemented, lessons learned, and actions taken to honor the victims.

Flying in the ‘wild west’

Without changes to ensure the safety of the D.C. airspace in the years after the 2013 near miss, the situation at DCA worsened. Of the over 15,000 potential conflicts between helicopters and commercial aircraft from 2021 to 2024 the NTSB identified in its preliminary report, 85 recorded events in that period saw less than 1,500 feet of lateral separation and less than 200 feet vertically.

At least once per month in the airspace around DCA from 2011 to 2024, the in-cockpit Traffic Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) used to warn commercial airline crews of nearby traffic generated a critical, action-oriented resolution advisory (RA) due to proximity to a helicopter. The NTSB claimed in over half of those instances the helicopter may have been flying above the maximum route chart altitude.

Shortly after that data was published in March 2025, then acting FAA Administrator Chris Rocheleau told a U.S. Senate committee he felt “something was missed” by the agency, given the NTSB’s data came from the FAA’s own databases. While the FAA was principally responsible for recognizing these alarming trends, no safety data was shared with other D.C.-area operators, including the military — hamstringing anyone’s ability to catch issues before they became fatal accidents.

This dysfunction was exacerbated by the fact that the FAA and the Department of Defense maintained entirely separate safety reporting systems. The Aviation Safety Information Analysis and Sharing (ASIAS) program, the FAA’s overarching safety reporting system, had no interaction with the Army Safety Management Information System (ASMIS) program, which the branch’s aviators use to track mishaps.

Army officials told investigators they were only ever aware that Army helicopters set off TCAS RAs for fixed-wing aircraft if such an alert resulted from an incorrect action by an Army pilot, known as a pilot deviation. In situations where visual separation was being applied properly but aircraft still came in close proximity to each other, the Army was rarely notified — even if an RA prompted an aircraft to abort its landing, as was sometimes the case. Fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters operate on separate communications frequencies near DCA and cannot hear each other’s transmissions to and from controllers.

An RA is not always indicative of a noncompliant or illegal operation, though the sheer frequency of their occurrences at DCA suggests more systemic issues. Army officials and FAA controllers told NTSB investigators they believed that in the case of most of the RAs received at DCA, visual separation was being applied properly by both aircraft.

This lack of data sharing extended beyond the military. Rick Dressler, site manager at air ambulance provider MedSTAR Transport Aviation, said during the NTSB investigative hearing he only became aware that his organization’s helicopters were setting off RAs because he read about it in a Washington Post article published a month after the crash. Because of the reporting, MedStar subsequently adjusted its operations at the Georgetown University Hospital helipad — which sits right under the final approach for Runway 19 at DCA — to avoid close proximity with DCA traffic.

Smith, the Prince George’s County police pilot, told investigators he was particularly disgruntled with DOD helicopter operators because of their disregard for other groups’ missions in the D.C. airspace, a concern echoed by Dressler at the NTSB hearing. A few years prior to the crash, Smith filed a formal complaint with the DOD in 2021 after he had encountered military helicopters flying through active police orbits.

“We’ve had quite a number [of close calls] with DOD assets,” Smith said, attributing this to “a lack of understanding in the DOD community of what law enforcement is actually doing. … You guys have no clue what we’re doing, and there’s going to be a catastrophic event if you guys don’t understand what’s going on.”

After filing that complaint, his organization started a quarterly fly-in of all helicopter users in D.C. to spread awareness. “Participation from DOD units was good at the start,” but it has since “tapered off,” Smith said.

At PSA Airlines, only one pilot out of four interviewed by the NTSB had an accurate and complete understanding of the structure of the D.C. helicopter routes — an individual who happened to have seven years of prior experience as a military pilot in the area. Two pilots had no awareness that published routes for helicopters even existed.

One DCA-based captain said it would have been “really helpful for us to have [had] more awareness if we would’ve known that there’s like a specific helicopter route in that area.” A line check airman said for PSA pilots, the helicopters operating in the D.C. airspace felt like the “wild west.”

A spokesperson for PSA, a party to the investigation, did not comment directly on the pilots’ knowledge of D.C. airspace but said “aviation safety requires multiple layers of compliance with detailed procedures, restrictions and operational standards across the full range of pilots and air traffic controllers. Together, these layers have made the U.S. aviation industry the safest in the world.”

The 12th Aviation Battalion’s chief standardization pilot said it was “very common for new pilots to the area to not understand the amount of volume that goes in and out of” the area around DCA.

Van Vechten, the former brigade standardization officer, said at the investigative hearing he wasn’t aware that, per DCA tower policy, traffic never arrived “straight in” to Runway 33 and always circled from Runway 1. Retired NASA human factors research psychologist Dr. Steve Casner said at the NTSB hearing that a pilot having an accurate mental map of traffic around them is “essential” to anticipate where traffic might appear.

Many other unit pilots said they were only used to seeing traffic land on Runway 1 and rarely witnessed an arrival on Runway 33. Some said it would have been common to misidentify traffic landing on Runway 33 for those they were used to seeing lined up for Runway 1, leading them to believe this may have been what Lobach’s instructor, Chief Warrant Officer 2 Andrew Eaves, saw from the cockpit the evening of Jan. 29 when he told air traffic control he had the CRJ in sight.

“I’m assuming, I’m guessing, I would bet money that [Eaves] was looking at the aircraft at Wilson Bridge [lined up for Runway 1], and that’s the one he was talking about,” Van Vechten told investigators. As of April 2025, less than five percent of DCA flights landed on Runway 33, something Casner said could contribute to expectation bias among pilots about where to look for traffic.

To help with traffic avoidance, the NTSB has for years emphasized the usefulness of GPS-based Automatic Dependent Surveillance Broadcast technology that, depending on the configuration, can broadcast aircraft traffic information (ADS-B “Out”) and/or show it on a cockpit avionics screen or pilot tablet (ADS-B “In”).

At the time of the crash, the Black Hawk had its ADS-B transmitter turned off in accordance with a controversial DOD-FAA agreement that allowed operations with the technology disabled for national security reasons.5 However, in order for ADS-B Out on the helicopter to have made a difference to the CRJ pilots — who already had TCAS — the CRJ would also have needed ADS-B In.

The CRJ did have ADS-B Out turned on and its location would have been displayed on the Army pilots’ knee-mounted tablets, but battalion aviators said they were trained not to look down at those tablets when flying through D.C. airspace in order to focus on looking outside, scanning for traffic.

Mistrust, miscommunication and mismanagement

Inside the DCA tower, the ground controller working at the time of the accident — who was fully certified on all positions — said in an NTSB interview they had filed several voluntary safety reports over the years about another persistent issue at the airport: the spacing between aircraft on final approach.

This controller, in addition to several others at both DCA and Potomac TRACON, said that aircraft arriving at DCA would often become so compressed that the airport lacked the four-mile spacing it needed for the tower to get departures out between each arrival. When aircraft on final became compressed, and without adjustments to the airport’s arrival rate, controllers said they felt the need to “offload” traffic to Runway 33. This was the exact situation on the night of the crash, the NTSB said in a summary of its findings.

Staff would often request additional space between aircraft from Potomac TRACON using an electronic communications program, the ground controller added, but doing so was often ineffective. “We deal with it all the time where we have to call over and say, hey, we’ve got this spacing request in [but] we’re not getting spacing,” they said.

An FAA risk assessment said that up to the point where control of an aircraft switches over to the tower, Potomac TRACON delivered four-mile spacing over 90 percent of the time. However, an average of one mile was lost between aircraft due to varying final approach speeds, the assessment added. When each aircraft crossed the runway landing threshold — the point that controllers from both facilities agreed was the true metric of proper separation — four miles of separation were provided just 61 percent of the time.

This procedure was codified in a handshake agreement rather than in an official letter of agreement like at other air traffic facilities, the NTSB found. An NTSB investigative report said that controllers in both the tower and the TRACON experienced a “shared frustration” about the spacing issue. DCA tower controllers felt their requests for more spacing fell on deaf ears, while TRACON controllers felt they didn’t have enough physical airspace to work the high volume of traffic with more spacing.

For that reason, the ground controller kept filing reports through the FAA’s anonymous Air Traffic Safety Action Program (ATSAP), which an introductory FAA video shown to new controllers described as an initiative that “empowers our proactive safety culture.”

“I’ve filed multiple ATSAPs. Other people have filed ATSAPs about the spacing on final,” the controller said. “The feedback I got [from the FAA] was the problem with filing ATSAPs is we can’t tell if this is an individual who can’t do their job correctly or if this is a systemic issue.”

On Jan. 29, the FAA got its answer.

Write to Will Guisbond at will@theaircurrent.com

Elan Head, Jon Ostrower, Brian Garrett-Glaser and Howard Slutsken contributed to this report.

Subscribe to The Air CurrentSubscribe to The Air Current

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention