Log-in here if you’re already a subscriber

Air safety reporting is made accessible without a subscription as a public service. Subscribe to The Air Current for full access to our scoops, in-depth reporting and industry analysis.

On Oct. 25, 1999, a Learjet Model 35 spun into the ground near Aberdeen, South Dakota, killing all six people on board, including professional golfer Payne Stewart. The pilot and co-pilot had been unresponsive to air traffic controllers for nearly four hours prior to the crash; when U.S. Air Force F-16 pilots intercepted the Learjet, they observed that its forward windshields appeared to be frosted over. The National Transportation Safety Board concluded that the aircraft experienced a loss of pressurization that incapacitated the pilots, although investigators were unable to determine why the flight crew failed to receive the supplemental oxygen they needed to remain conscious.

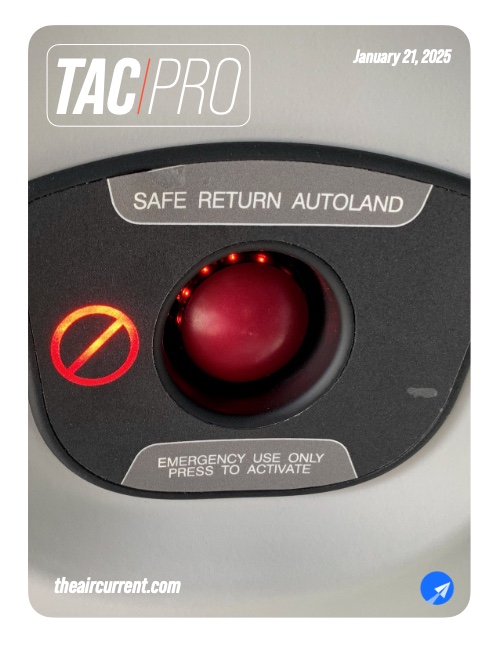

That accident was the direct inspiration for Garmin’s Emergency Autoland, which is designed to take control of an aircraft and fly it to a safe landing in the event of pilot incapacitation — the inability of a pilot to carry out their duties for physiological reasons. The system can be activated by pilots or passengers with a single button press and will also activate automatically in some cases, including following sustained use of Emergency Descent Mode, another Garmin feature that initiates an automatic descent in response to abnormally low cabin pressure.

That is apparently what happened on Dec. 20, 2025, when a Beechcraft King Air B200 flown by Buffalo River Aviation became the first aircraft to deploy Autoland to a successful landing in real-world operations. The King Air was on a repositioning flight out of Aspen, Colorado with two pilots and no passengers on board when it “experienced a rapid, uncommanded loss of pressurization” while climbing through 23,000 feet above sea level, according to a statement from Buffalo River Aviation.

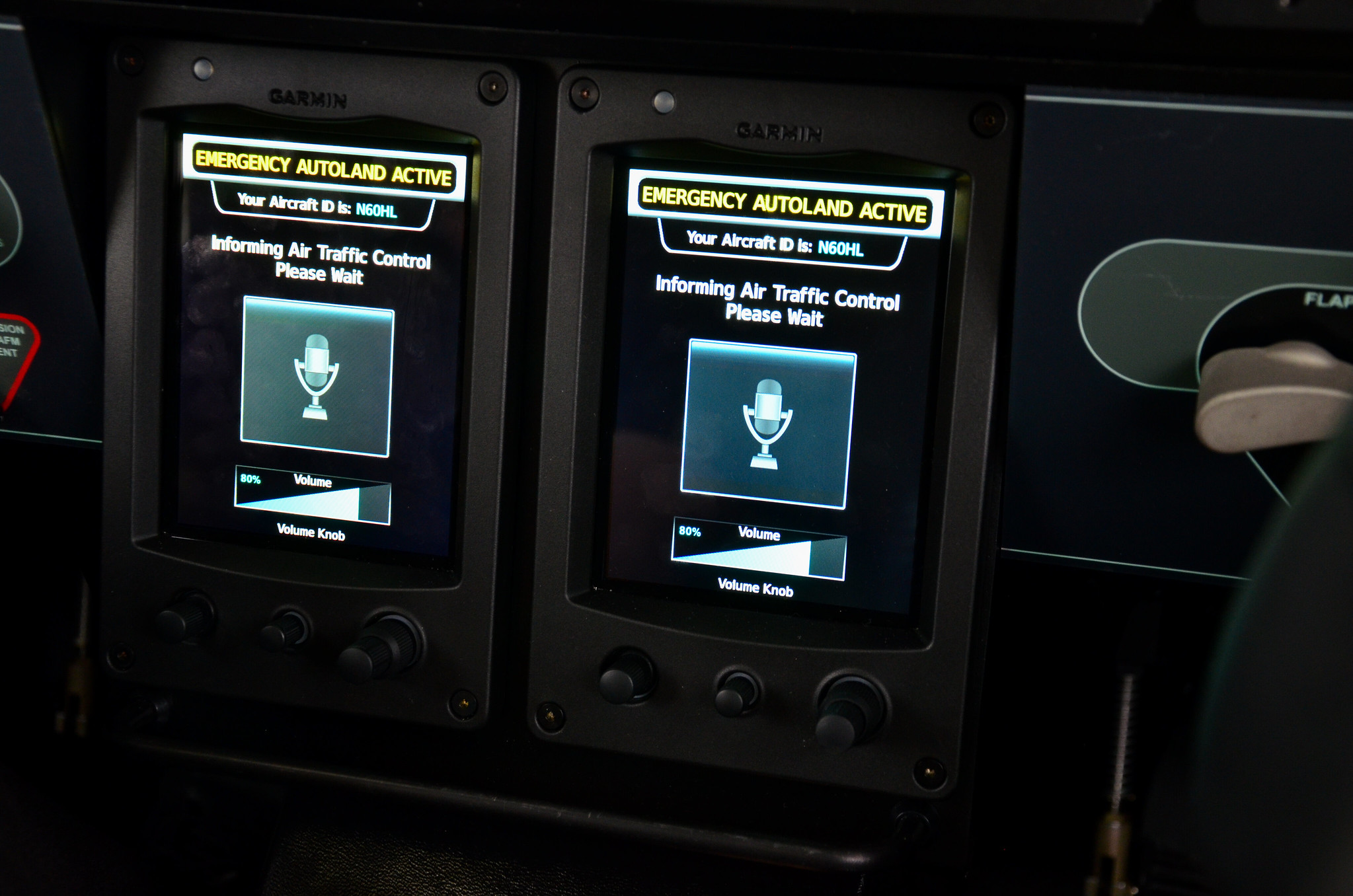

The aircraft management company based in Bentonville, Arkansas said Emergency Descent Mode and Autoland “automatically engaged exactly as designed when the cabin altitude exceeded the prescribed safe levels.” Autoland proceeded to navigate the aircraft to Rocky Mountain Metropolitan Airport (KBJC) near Denver while broadcasting its position and “pilot incapacitation” over the radio.

The event would have been a dramatic demonstration of Autoland’s ability to avert the type of crash that killed Payne Stewart, except for one minor detail: the pilots on board the King Air weren’t actually incapacitated. According to Buffalo River Aviation, the pilots immediately put on their oxygen masks following the depressurization, then decided to leave the automatically activated Autoland engaged “due to the complexity of the specific situation.” Citing the authority of the pilot in command to deviate from any rule to the extent required to meet an in-flight emergency, the company said the crew “consciously elected to preserve and use all available tools and minimize additional variables in an unpredictable, emergent situation.”

This is not exactly what Garmin and the Federal Aviation Administration had in mind when they certified the system. Although Autoland underwent a rigorous design and testing process, the safety case underlying its certification assumed the incapacitation of the flight crew — what Phil Straub, executive vice president of Garmin’s aviation division, described to The Air Current as a “post-catastrophic” event.

“If you lose a pilot or the crew of an aircraft, the chances of a successful outcome of the flight are really quite low,” he said. That calculus allowed Garmin to certify its Emergency Autoland to lower standards of reliability than, for example, the Category III autoland systems on transport category airliners, in turn making it affordable and accessible for more aircraft.

The use of Autoland by fully conscious pilots is leading Garmin to revisit some of its assumptions around the technology. “I think we’re learning from this event,” Straub told TAC. So too is the FAA, which said it is investigating the deployment.

While fully incapacitated pilots would have made for a simpler, more satisfying story, events as they actually unfolded make for a more interesting one — highlighting key unresolved questions around the appropriate roles of pilots, operators and manufacturers in an age of increasing automation. When capable pilots are overseeing the operation of a highly automated system that limits their ability to intervene, how should they be held accountable for it?

Putting the pieces together

Straub, who joined Garmin in 1993, recalled that he was working as lead software engineer on one of the company’s early integrated avionics products, the GNS 530, at the time of the Payne Stewart crash. Straub is also an experienced pilot and flight instructor, and the accident haunted him. “I think for anyone that’s a pilot, [they] always asked themselves: what would have happened to me in that situation?” he said.

In the years that followed, Garmin developed products that became the building blocks for Autoland. “Obviously we have a big background in navigation,” said Straub. “But then as time goes on, we start to synthesize voice — we can do speech recognition, text-to-speech — and we developed very capable digital autopilots over time. So by 2011 was roughly the time frame we just thought, you know, we’ve got all these pieces. Can we bring this together?”

While Garmin already had many of the elements for Autoland, integrating them into a functional system was no small feat. When the system is activated, it engages the autopilot and autothrottle to either maintain wings level and hold speed, or climb to avoid nearby terrain while computing a destination and route. The company needed to create a robust, explainable algorithm to select the most appropriate diversion airport based on a number of factors, including stable characteristics like runway dimensions as well as more dynamic variables such as wind and precipitation, which the system pulls from various datalinks.

Once the system navigates to the airport, it needs to stick the landing. This required developing control laws for non-fly-by-wire aircraft to execute the approach, flare and touchdown — and then maintain centerline on rollout, brake the airplane to a full stop and shut down the engines. Crosswind landings were a particular challenge, Straub noted, because the ways in which human pilots intuitively compensate for a crosswind are difficult to translate into software. Garmin began flight testing for Autoland in 2014 but it was nearly two years before the company performed its first fully automated landing in early 2016.

Straub readily acknowledges that Garmin was not the first company to land a plane using automation. Category III instrument landing systems (ILS), which routinely fly airliners to the runway in conditions of extremely low visibility, have “been around for a very long time,” he said. However, the established standards for these autoland systems require double or triple redundancy across autopilots, radar altimeters and navigation equipment (which is also the bar for companies designing autonomous systems for normal use). Category III autoland additionally requires qualified airports equipped with suitable ILS or other navigation facilities.

According to Straub, Garmin believed that these requirements in their entirety were prohibitive for its target market of general and business aviation aircraft, which frequently operate out of smaller airports. “We knew that if we [went] in with the notion that availability has to be at the … 10-9 level, then it was going to make this out of reach, out of touch for a lot of the general aviation/business aviation fleet where we were initially focused,” he said, referring to the target level of safety for transport category aircraft of no more than one catastrophic event per billion flight hours.

Related: Special Report: The number at the center of an eVTOL safety debate

Garmin thought it had a strong safety case for relaxing some of these standards for a system designed for emergency use only. The FAA and European Union Aviation Safety Agency generally agreed, although Straub declined to provide specifics on which requirements were relaxed or the software development assurance level of the Autoland function. The FAA also did not provide specifics, telling TAC in an email: “Multiple FAA divisions collaborated on the Autoland certification. We certified it to deploy in emergency situations when pilots cannot operate the aircraft. The FAA accepts the use of emergency systems to avert serious incidents, as long as the equipment performs as intended and complies with safety regulations.”

Even with these allowances, Garmin was required to conduct an extensive flight test campaign and analysis of failure modes, finally achieving initial certification of the system in 2020. FAA-approved language in the accompanying airplane flight manual supplement (AFMS) for the King Air B200 states that “use of the Emergency Autoland system is limited to emergencies resulting from pilot incapacitation” and that “Emergency Autoland use during normal operations is prohibited.” The FAA confirmed that “pilots can activate the Autoland system if they are partially incapacitated,” while reiterating that “pilots are prohibited from using the system unless there is an emergency.”

Straub said that while Garmin did not design Autoland “to where it precluded the pilot crew from being functional and operating at their station, we designed it so that it would work if they were able to do nothing.” The company expected the system to be activated by non-pilot passengers and designed a touchscreen interface that would allow them to communicate with air traffic control while keeping their hands away from the flight controls and autopilot disconnect button, he said. “One of the biggest worries was, if you didn’t have crewmembers there, you didn’t want frantic passengers trying to do things they shouldn’t do,” Straub explained.

The company spent less time thinking about what a conscious pilot would want during an Autoland activation, such as the ability to direct radio communications. Pilot and podcaster Max Trescott was flying in the vicinity of the Buffalo River King Air on Dec. 20 and recorded one of its pilots saying that they were only able to communicate on the emergency or “guard” frequency, 121.5 MHz. “It’s not going to let you switch unless you cancel the Autoland,” someone else chimed in over the radio.

The AFMS has only a high-level description of how Autoland works and does not elaborate on limitations that a monitoring pilot might want to know about, such as the fact that the system is not programmed to execute a go-around. Information about failure modes is limited to the type of faults that might occur after an unintended activation or prior to dispatch. And while Garmin and aircraft manufacturers have developed a number of videos, e-learning products, briefing sheets and air show displays related to Emergency Autoland, it is not clear how many operators, if any, have developed formal pilot training for the Autoland system or standard operating procedures for how pilots should interact with it.

Garmin is already studying the lessons of this first real-world deployment and thinking about how to apply them. “As activations take place, Garmin is going to learn from those involved where we can make enhancements to the system,” the company told TAC in a follow-up email.

The FAA said it evaluates information as it becomes available through the regular safety oversight process. “Based on the findings, follow-up actions may include updating training and procedures,” the agency said.

The accountability problem

While it is natural for pilots to want control over their aircraft, deciding how to allocate responsibilities between humans and automation is one of the thorniest problems in the development of any automated system. When pilots are “in” or “on” the loop — meaning responsible for or capable of intervening in the operation of the system, respectively — it can be challenging to design an interface that correctly anticipates the myriad ways in which the interaction between the pilot and machine could go wrong. Many autonomy researchers believe that it is often preferable to take humans out of the loop entirely, which is essentially what Garmin did with Autoland when it assumed pilot incapacitation.

Anna Dietrich of AMD Consulting, who specializes in policy and certification topics surrounding advanced air mobility and autonomy, told TAC by email that fully automating all of the tasks necessary to perform a given function is known as “vertically applied automation” and is “generally safer as it reduces or even eliminates the potential for human-machine interaction errors.” These errors include things like mode confusion, such as when a pilot fails to change an autopilot’s mode and programs an incorrect command, which was the likely cause of the Air Inter Flight 148 crash that killed 87 people on an early Airbus A320-100 in 1992. Another common trap is poor situational awareness on the part of the human when a reversionary mode is activated, such as when an autopilot disconnects with little advance warning to the pilot.

The aviation industry has successfully integrated vertically applied automation in certain systems such as full authority digital engine control (FADEC), which automatically controls fuel flow, power output and other engine parameters more consistently and effectively than a human could. When it comes to flight control in normal operations, however, humans are still firmly in or on the loop — and the reasons for this have as much to do with culture and regulations as with technical limitations.

Under the existing regulatory framework, the pilot in command is directly responsible for, and is the final authority as to, the operation of the aircraft. They are therefore accountable for their actions during flight, in the sense that they have to answer for them.

“Accountability is different from just the responsibility to perform a function or task and can only reside with a human actor, or an organization composed of human actors,” Dietrich explained. “Much of accountability in aviation is focused around safety outcomes and, while there is explicit accountability in the regulations, it is often implicit based on decades of common practice.”

The introduction of Emergency Autoland does not fundamentally change this framework. While the successful landing at KBJC relied on Garmin’s technical execution of vertically applied automation, if the outcome had been unsuccessful, the pilots almost certainly would have been faulted for using it, whether or not they had the information they needed to properly supervise the system. Buffalo River Aviation’s statement on the event reinforced the pilots’ ultimate authority and accountability without questioning the design of the automation, asserting that “the pilots were prepared to resume manual control of the aircraft should the system have malfunctioned in any way.”

Groups like the standards organization ASTM are exploring how the allocation of accountability could change with the introduction of increasingly autonomous systems, but even taking pilots out of the aircraft may not disrupt the existing accountability framework anytime soon, according to Brandon Suarez, vice president of UAS integration at Reliable Robotics. The company is developing what it describes as a “continuous engagement autopilot,” initially for the Cessna Caravan, that will operate across all phases of flight including taxi, take-off, enroute and landing. The system is designed to be used by an onboard pilot who will clearly have both responsibility and accountability, but is also intended to be a stepping stone to uncrewed flight, at which point Reliable expects the pilot-in-command position will simply become remote.

“A remote pilot is responsible and accountable for the safety of the flight operation, and it’s going to be a highly-trained, highly-qualified professional,” Suarez told TAC by email. “One of the reasons we’re doing that is because that’s how the aviation ecosystem is set up today and we don’t want to change it.”

Because Reliable’s system is intended for normal use, it is designed to meet or exceed the safety requirements for Part 23 small airplanes in addition to the existing autoland standards. Beyond the associated technical aspects, Suarez said the company is spending much of its time developing the human-machine interface that will allow the pilot, whether onboard or remote, to correctly understand the aircraft’s status and configuration and command changes to it — enabling pilots to maintain accountability.

“We are asking these questions such as, what is the information or capability that you have to give to an individual to hold them accountable for the operation of the aircraft?” he said. “We are also participating in the community of people that is thinking deeply about this topic of accountability, and those are important conversations, even if theoretical at this stage.” Referring to the Emergency Autoland activation, he said: “The industry at large can learn from this incident.”

A tool for bad days

By assuming pilot incapacitation during the certification of the system, Garmin and the FAA sidestepped some of the toughest problems associated with the introduction of autonomy on the flight deck, but the decision by conscious pilots not to cancel Autoland returns these problems to the fore. The fortunate outcome of the Dec. 20 event will allow them to be addressed in a deliberate way, rather than in the fraught context of an accident investigation.

The Buffalo River Aviation pilots have not yet spoken publicly about their experience or thought process during the flight. That has not prevented many people from passing judgment on them, with some praising their decision to rely on Autoland and others condemning them for it.

Ultimately, there is no simple way to compare a deterministic mechanical system like Autoland, which performs repeatably to certain standards within the limits of its certification, to the “black box” of a human pilot, who might be having a good day or an exceptionally bad one, particularly during an abnormal situation like a rapid loss of cabin pressure. The authority of the pilot in command to deviate from any rule during an in-flight emergency is one way of accommodating the variability of emergency situations and human performance, and Buffalo River Aviation said it was grateful to its pilots “for their exceptional judgment and execution of protocols.”

The fact that Autoland was certified for emergency use only makes for a natural comparison with the Cirrus Airframe Parachute System (CAPS), introduced in 1998 as the first general aviation whole-plane parachute system produced for a certified aircraft. CAPS was controversial at the outset and there have been some deployments in which the pilot could have conceivably landed the aircraft manually, subjecting these pilots to similar scrutiny from their peers.

Nevertheless, Cirrus credits CAPS with saving 270 lives in the quarter century since its first real-world deployment in 2002, and its use has been normalized in a way that Autoland may be soon. New Cirrus SR series pistons as well as G2 and G2+ Vision Jets now also come equipped with Emergency Autoland as standard equipment.

“There’s a certain level of trust that can only be built by seeing things work the way they’re intended,” said Dietrich. “I believe that this first successful deployment will go a long way towards normalizing the role of these types of automated systems and helping more people realize their true safety-enhancing potential.”

Write to Elan Head at elan@theaircurrent.com

Subscribe to continue reading...Subscribe to The Air Current

Our award-winning aerospace reporting combines the highest standards of journalism with the level of technical detail and rigor expected by a sophisticated industry audience.

- Exclusive reporting and analysis on the strategy and technology of flying

- Full access to our archive of industry intelligence

- We respect your time; everything we publish earns your attention